The World Bank aquaculture adviser recently visited aquaculture producers in Senegal

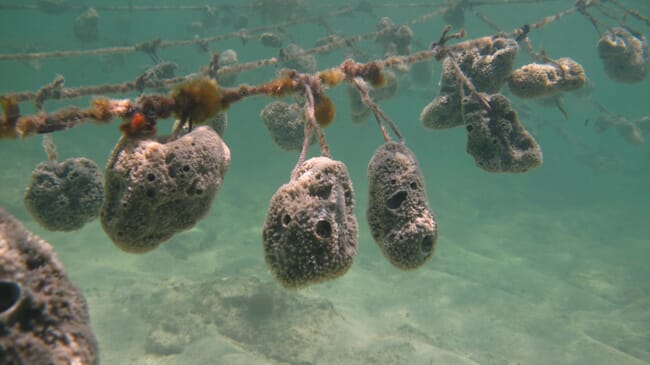

“Seaweed is becoming a big thing – for very good reasons. For its carbon sequestration potential, for issues of food security, for creating jobs, especially for women – it’s a crop that World Bank is looking to develop further, both with the private sector and governments,” he explains.

At the same time, however, according to Karisa, it’s a sector that needs an improved framework.

“One of the issues we have is that seaweed farming has been developing – in Africa and elsewhere – without proper certification and safety standards. We want governments to start formulating particular standards that are appropriate to those particular countries,” he reflects.

In order to help with this process, one of the bank’s key aquaculture research projects during 2022 – the results of which are due to be scheduled in 2023 – has been an in-depth study of the seaweed industry with focus in Asia, in a bid to learn how Asian success can be applied, and improved on, more widely across the world.

Karisa has worked with WorldFish and is currently a senior aquaculture specialist with the World Bank

“We’re doing a global market study, based on the experience in Asia, to see where future markets are going to be and look at new products in the offing. World Bank’s success in support of sovereign blue bonds can be expanded to include utilising the potential of seaweed to sequester carbon and other nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorous. This is challenging and new but also aspirational considering the contribution it can make to climate change mitigation, healthy oceans and improvement of livelihood of the most vulnerable,” Karisa explains.

Geographically speaking, one of Karisa’s main focus for growth in production of seaweed is Africa. And while the continent’s main seaweed sector is Zanzibar, he sees potential in other African regions, including Madagascar, parts of West Africa, Morocco and Egypt.

“The African continent is very rich in terms of where we can grow seaweed, but unlocking that potential is still a challenge,” he reflects.

Africa's main seaweed sector is based in Zanzibar, but the industry has huge potential in other nations © Umitron

Part of this, according to Karisa, is the lack of regulations for seaweed production, as well as the difficulty of obtaining licences to grow it in many African countries.

“I’m happy that we have very good support from within the bank – our management is very keen on what happens in this sector, but we want to see many more countries investing in this sector. The potential for jobs, especially jobs for women, is very high,” he says.

Warming inshore waters is another barrier to overcome – and this trend is encouraging the bank to look towards helping the seaweed sector move further offshore, where temperatures are more stable and so it should be easier to produce seaweeds with a more consistently good quality. However, Karisa admits that this transition – requiring investment and training farmers to use boats and consider qualifying as divers – will not be easy for all existing inshore seaweed farmers, who are used to operating in shallow waters, close to their homes.

Despite such challenges he notes that the public and private sector, and his World Bank colleagues, have been flocking to the organisation’s seaweed-related events.

“Previously, if the bank organised an aquaculture seminar, people didn’t find it useful to attend, but we had over 200 come to our two seaweed workshops and many others watching the recorded proceedings. We are changing the narrative that aquaculture is not important, and people don’t care about it,” Karisa reflects.

Striking a public-private balance

A further area the World Bank has been investigating relates to finding a balance between the public and private sectors when in comes to aquaculture investment.

“We’re trying to work more closely with the private sector – and bringing together the public and private sectors. While we are still working with governments, we want to see the environment for private investments improved,” Karisa explains.

Karisa believes that, while governments are crucial for laying the foundations for aquaculture development – private sector investment is vital for the longer term growth of the industry.

The World Bank hopes that aquaculture can find the right balance between government and private sector support © FISH4ACP

“As aquaculture starts to develop, we want to see government involvement – they incorporate environmental regulations, and might help establish hatcheries and feed mills, but eventually the government should play less of a role,” notes Karisa.

“What we’re doing is preparing guidelines for people who want to invest in aquaculture – be they governments or private sector, we want to see that they are guided in the right way and know when, where and how to invest,” he adds.

Looking ahead

With the challenge of keeping healthy aquatic ecosystems amidst pollution, loss of biodiversity and a dwindling fishery, it is no longer sufficient to try to stop the loss but the World Bank seeks to reverse the trend. In aquaculture, from 2023 onwards, more emphasis will be on where the bank sees potential for an increase in the production of low trophic freshwater fish, such as tilapia and non-fed extractive species such as sea cucumbers, oysters and mussels that allow and integrated circular culture systems that minimise waste. The industry will also see more alternatives to fishmeal – increased support projects that increase insect meal use for aquafeed.

“In order to reduce the dependence on fishmeal as a protein source and also reduce the waste from [agricultural] farms,” he explains.

The World Bank wants its aquaculture projects to become more regenerative in 2023 and focus on low-trophic species and circular systems © Marine Cultures

Karisa also believes that seaweed could be used as a substrate for feeding the insect larvae – thereby not only supporting seaweed production, but also reducing the carbon footprint for insect meal production– although this idea is still in its infancy.

One further activity he is involved in, includes looking at whether – and how – investors, as part of their corporate responsibility can be encouraged to support aquaculture projects that might not be purely economically-driven.

“We are looking at how to convince people to invest in things that can help with ecosystem services, and nature-based solutions for example, but many people still see aquaculture as a problem for the environment,” he notes.