Is an extension specialist at Louisiana State University, who also writes a monthly column for The Fish Site

Overall, according to Lutz it’s been a testing year – both in developing and developed countries – albeit for different reasons. But there are also glimmers of hope – notably in terms of the demand for good quality farmed seafood.

Tough times in ‘22

“The lows began post-pandemic and became much worse once the Russia-Ukraine conflict began. The whole problem with global grain supplies hit all animal production, but I believe it hit aquaculture even harder, because feed is such a large component of our production costs,” Lutz observes.

“A lot of the places around the world where commercial aquaculture was just starting to gain momentum were hit disproportionately hard. Especially in Africa and developing nations in other regions. That was a big blow,” he adds.

Lutz also bemoans what he sees as “the cavalier attitude towards the role of science in most developed nations”, especially in his homeland.

“We have such a huge sector of the public that are proponents of science when it fits their agenda, yet when it comes to public debate and public policy about aquaculture it seems like the science takes a back seat,” he argues.

Examples he cites include Washington State’s decision to ban net pen farming of Atlantic salmon as they are not native to the region, but allowed – initially – people to farm steelhead, which is a native species, instead.

“Right there the science was abandoned. Seventy, 80, 100 years of science shows that those Atlantic salmon will never cause any genetic pollution should they escape from farms. They may have a temporary competition situation, but then they’re gone,” Lutz observes.

“Instead they allow for hatchery-reared steelhead which could interbreed with wild fish and cause genetic pollution if they escape. There’s not a lot of science there,” he adds.

“We’re seeing people disregarding science when it fits their agenda and aquaculture is an easy monster in the closet, as the general public doesn’t understand aquaculture. If the first thing they hear is that it’s terrible and ruins the environment, then that’s what they carry in their mind from than point forward. Maybe the problem is that there is a lack of scientific literacy and a lack of analytical thinking – we see that all across society, in things like anti-vaxxers,” he continues.

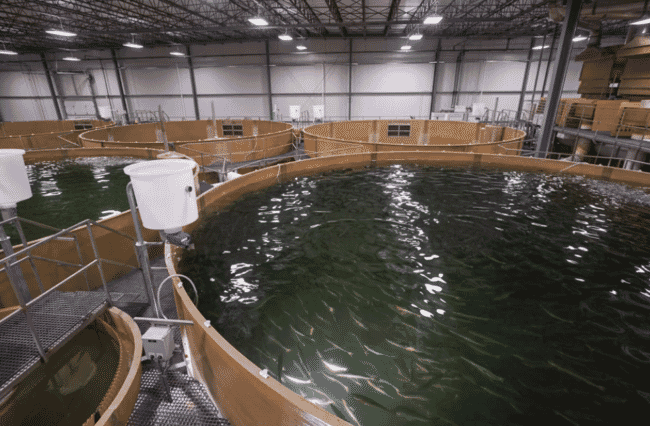

Another example he cites is the decision by the FDA to force AquaBounty to go through another environmental impact analysis this year, despite this having been covered exhaustively on numerous occasions.

Despite the farm being indoor and self-contained, thus making it virtually impossible for the salmon to escape into local water bodies, the FDA is making them jump through extra hoops

“They had to reconfirm that a triploid female salmon would have negligible environmental impact were it to escape into a stream in Ohio. It was just another example where science takes a back seat,” he argues.

The emergence of EHP in shrimp farms in Guatemala and Honduras is another trend that’s been a concern for Lutz, who has strong Latin American connections, although he’s confident that the farmers will come to terms with this.

Positives for ‘22

“I’m optimistic when I look at the interactions between aquaculture producers and consumers in many, many parts of the world. Although producers have been forced to increase their prices, consumers seem to be willing to accept those increases. We’ve seen that in a lot of countries in Latin America and also in Africa. If you look at price surveys from Ghana, tilapia producers have increased their prices but are still moving product,” Lutz notes.

“In some countries this might be because there aren’t a lot of good protein options. But in a lot of countries there still are – people could switch to chicken, for example, instead, but we don’t see as much of that as I feared we would,” he explains.

Looking ahead

One positive trend, Lutz notes, relates to the increased willingness of people to invest in aquaculture – when the time is right.

“One impression I get is that a lot of the capital that’s required for more feed mills and processing plants in Latin America is going to be there when economic conditions improve,” he reflects.

“A lot of the wealthy business people in these countries have money and, when things turn around, we’ll see a lot of these tilapia farms expanding, we’ll see new farms coming in and we’ll see some other species being developed. I’m not sure how much we’ll see that surge in shrimp production, but I think we’ll see it in tilapia – especially in Brazil and Colombia, as well as possibly in Mexico to some extent,” he explains.

However, Lutz expects that this might take more than a year to really be noticeable, and that the status quo is – on balance – likely to be maintained in 2023.

“I think some of the challenges may become a little more intense before we turn the corner but our industry has had most of 2022 to adjust and learn to pay attention to the details, so I don’t see any calamities,” Lutz argues.

They are known as pirarucu in Brazil, where they are mainly farmed

In terms of species, he believes that species to look out for include pirarucu / arapaima – which are mainly grown in Brazil at the moment.

“It’s still a fledgling business and hasn’t quite grown to international export markets, but there is now some exporting going on and I think that will be a fish that will really be commericalised for export.

“It’s easy to reproduce, they grow very quickly and the flesh is super high quality – perfect for very high quality retail outlets,” he concludes.