Nikolik argues that the total tax raised will be marginally more in the short term but less in the longer-term © Norway Royal Salmon

Rabobank’s chief seafood analyst is baffled by the plans to add a 40 percent resource rent tax on salmon production. The proposal, which emanates from the country’s left-wing politicians, might – at a glance – seem like an easy way to raise public money from a sector that relies largely on a public resource, the ocean, for its existence. But, as Nikolik points out, it has some serious flaws.

“If you calculate the pluses and minuses of the tax strategy the Norwegian government might raise more corporation tax by increasing it from 22 to 40 percent but they will lose some money on selling licences and lose money on taxing income,” he points out.

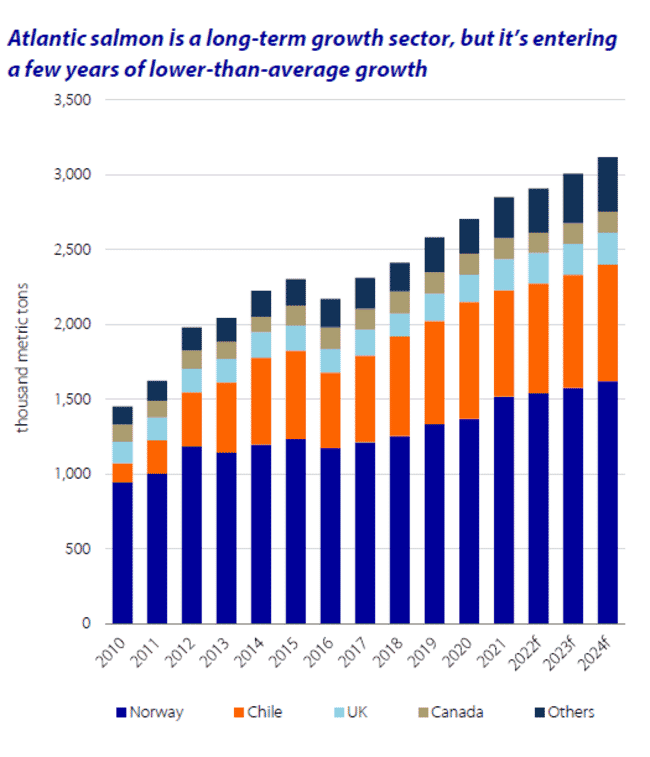

The end result is that the total tax raised will be marginally more in the short term, and arguably less in the longer-term, as it could reduce the rate the sector will grow at.

“If passed it will add only a few percent to the Norwegian budget – and those few percent could become a negative figure in two to three years' time, because it will lead to lower growth in salmon sector. Hatcheries for big smolts are super capital-intensive and require good profitability to be worthwhile. A lot of companies have scrapped these projects which means that production of big smolts – which, along with new licences, are the main driver of growth in Norway’s salmon sector – is going to stop. So that could cut Norwegian growth in half,” explains Nikolik.

“If Norway’s long term supply growth rate goes from its expected level of 3 to 4 percent, down to 1 to 2 percent it will lead to higher long term prices – thus good news for Chile, Scotland and Canada,” he adds.

Intriguingly, Nikolik also wonders if the governments of countries such as Chile and Canada might look to emulate the Norwegians’ tax plans, rather than capitalising on their new-found advantage.

“Left governments are looking at this reserve stack and thinking that ‘if Norway needs it then maybe we need it too’.

Reversing consolidation

It might also pave the way for some of Norway’s smaller salmon producers – those harvesting under 5,000 tonnes of fish a year are likely to be exempt from the tax – to outmuscle the big players when it comes to bidding on new licences.

The proposed tax measure may reverse the consolidation seen in the segment © Rabobank

“When the licences are sold now it will most likely be small companies that will buy them. It will reverse the consolidation. Previously every year the large players have a bigger chunk of Norwegian production – either through consolidation or because they are always winning the licence bidding – because they get the most volume and value per licence,” Nikolik explains.

Short term impacts

One thing that Nikolik expects is for the mere possibility of the tax to alter the farmers’ end of year harvesting strategies, whether the legislation is passed or not on 4 January.

“In the very short term it could have a huge impact. It depends what the producers think about the likelihood of the tax being passed. But if they are profit maximising they will do a massive harvest in December – they could even freeze product and sell it in 2023 – the tax is based on when the salmon was harvested, not when it was sold,” Nikolik explains.

Such an end of year glut could overturn predictions that the global salmon sector could have a year of contraction for the first time since 2016, and also put a dent in Q4’s salmon prices.

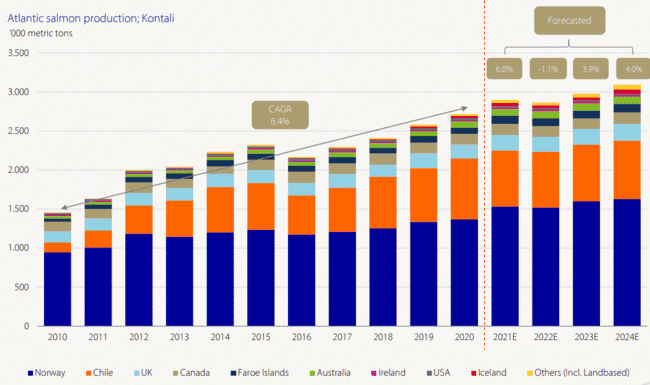

The tax rate is tied to the Nasdaq spot price for salmon, which could be misleading © Kontali and Rabobank

Another short-term impact is related to the fact that the tax rate is tied to the Nasdaq spot price. This, however, is not representative, given that many farmers sell the bulk of their fish on longer term, fixed price contracts.

“The contracts tend to be quite a lot lower than the spot price, which is very volatile. The spot price was at NOK 120 per kilo for a short time, while the price for those on six month contracts was typically NOK 60 or 70 per kilo at the same time,” Nikolik explains.

“Because the tax is calculated according to the spot price, a company that has made a small or medium sized profit on their contract will suddenly get hit with a huge tax bill, so they could start to lose money,” he adds.

As a result, according to Nikolik, the salmon producers are currently unwilling to enter contracts and so are selling at spot price to limit their tax risk.

The bill still needs to pass - and the margins on the vote are extremely close © Lingalaks

“That has already had an impact – processors are struggling to find longer term contracts for 2023, but they themselves have a contracts with the retailers. So in the end the whole value chain is destabilised,” he points out.

Unsurprisingly, Nikolik explains, it’s the area of the draft legislation that’s received the most criticism, so is likely to be changed.

Will it pass?

Whether the bill will actually pass is thought to be extremely close. While the left-leaning parties have 100 of the Storting’s 169 seats so could pass the legislation easily if they united behind it, the coalition includes the centre party, who are thought to be divided over the bill.

“If half the centre party’s 28 MPs and everybody on the right vote against the bill, then you only need two votes in the labour party against it for the law to fail,” Nikolik explains.

Meanwhile, whether the tax hike will be as dramatic as first set out also remains to be seen – as the government has said that the details are still open to revision.

The proposed tax could limit growth and innovation in one of Norway’s leading and most sustainable industries © Aker Biomarine

Conclusions

Regardless of whether the legislation is passed, it has certainly raised all manner of questions.

“It’s an unprecedented moment, not just for salmon, but also the world, if we start taxing resource industries – it’s a new concept of what tax should be,” notes Nikolik.

“The farmers bought the licences, they’re paying an additional tax per kilo since 2019, as well as corporate and eventually income tax when the corporate profits are paid to the owners, but the government is saying the sea is national property and the farmers have made too much money off it. A broader part of society need to benefit from these national resources, so we need to tax them more,” he adds.

And the timing of the plan makes it all the more extraordinary to Nikolik.

“They could limit growth and innovation in one of Norway’s leading and most sustainable industries for an estimated less than 4 percent in additional tax revenue – in a period of record government revenues generated by the high oil and gas prices,” he observes.

“One could argue that using the high oil and gas revenues and investing these in salmon farming or ensuring a lower tax burden on this industry will ensure growth and innovation in aquaculture. A thriving aquaculture industry will likely be more positive for the long term Norwegian government budget,” he adds.