First described in 1822, Arapaima gigas is the most recognised member of its family, the Arapaimidae. Known as Paiche in Peru and Pirarucu or Arapaima in Brazil, the fish shares its genus with several similar, yet less common, species: A. agassizii, A. leptosoma and A. mapae.

All members of the genus reach large sizes, but A. gigas (hereafter referred to simply by its common name in English, Arapaima) is by far the largest, with individuals greater than 3 metres long, weighing over 200 kg often reported.

A. gigas was originally found in much of the Amazon and Essequibo watersheds, with the exception of Bolivia and southern Peru. Over the past several decades, however, the fish has been introduced to those specific regions and to several other parts of Peru and Brazil. Other reported introductions include Cuba, Mexico, Colombia (beyond its natural range in the south of the country), Ecuador, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, India and China. Many of the initial introductions in Asia were associated with the aquarium trade, and most established populations throughout that region are probably the result of accidental releases despite the fact that Arapaima fingerlings currently command anywhere from $60 to $150 apiece throughout the region.

Arapaima exhibit phenomenal growth rates, often gaining 10 to 15 kg during their first year. They are obligate air breathers, and as a result they can tolerate low dissolved oxygen levels. They are easily spawned year-round in captivity and the resulting fry are developmentally advanced at hatching. Arapaima readily consume pelleted feeds, and they don’t just tolerate crowded conditions during grow-out but seem to prefer them.

© E. Orjuela

History

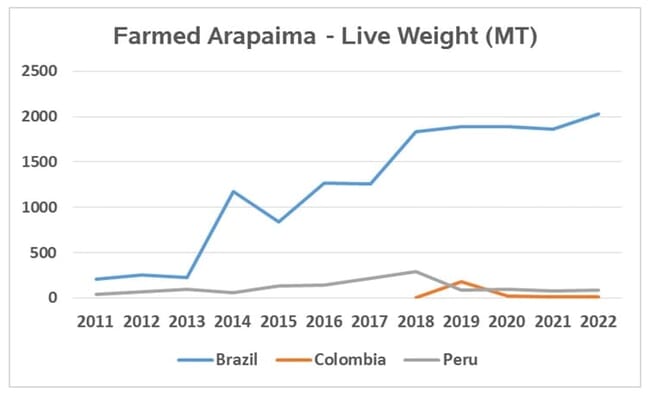

Over the course of the last century, Arapaima were almost fished to extinction throughout much of their natural range. As a result, in 1975 the species was listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), prompting attempts at culturing these fish during the 1980s and 1990s. Over the past decade production has increased significantly in several countries, but volumes are still comparatively low.

Arapaima meat has often been compared to that of halibut – free from bones and available in large portions. Domestic markets in Peru, Brazil and southern regions of Colombia have seen retail prices of $20 to $30 per kg for Arapaima portions and fillets in recent years. Coupled with limited supplies, this has resulted in high prices and inconsistent availability in export markets. Demand for other Arapaima products is also expanding but due to its CITES designation international trade in any Arapaima product must be certified as farmed, with a closed life-cycle utilising captive broodstock and hatchery-reared fingerlings.

© Greg Lutz

Culture methods

As is the case with many emerging species, although interest in farming Arapaima has increased over the past decade there is still no single, standardised production method. Galvez Escudero and Mendoza de la Vega (2024) provide an excellent analysis of the current knowledge regarding captive reproduction in A. gigas. This area of focus has taken on significant importance because the supply of hatchery-raised fingerlings has failed to meet demand in recent years. The species has comparatively low fecundity when weighed against the costs involved in maintaining breeding stocks, since Arapaima do not begin to reach sexual maturity until they are four years old, with weights of 40 to 60 kg at their first spawning.

Perhaps the simplest approach to fingerling production begins with stocking a number of mature fish in large open ponds at the onset of the rainy season, where they will pair up, build nests and spawn. In recent years, the development of blood tests and molecular techniques has made the process of sexing broodstock much more efficient. A large female may produce more than 10,000 eggs, which both parents will guard. Once the eggs have hatched the parents continue to protect the young for three weeks or longer, as they remain in a compact school near the nest. Hatchlings grow rapidly during this period, consuming zooplankton and other natural food.

At three to four weeks post-hatch fingerlings can be collected. Alternatively, eggs can be collected and larvae reared under hatchery conditions at high densities. When paired fish are maintained in smaller isolated ponds they may spawn five or more times per year, but many females fail to ovulate or synchronise spawning behaviours with males. This practice can also result in high levels of inbreeding on many farms, limiting overall productivity.

© E. Orjuela

Once the young are removed from the breeding pond they are trained on high-protein manufactured feeds at high densities. Lima et al. (2020) demonstrated that frozen zooplankton could replace live feed during the weaning process, allowing for improved biosecurity and management. Nonetheless, whether in spawning ponds or larviculture settings, care should be taken to minimise the presence of ostracods when feeding very small Arapaima to improve survival. By the time they are 40 days old the fingerlings are typically fully trained on dry floating pellets. Oeda Rodrigues et al. (2019) determined that three feedings per day resulted in optimum growth, feed conversion and protein/energy retention during this stage of production.

At three months advanced fingerlings are 300+ grams, then stocked for grow-out, traditionally in ponds or cages. Research suggests that the optimal protein content for pelleted feeds during this phase is approximately 36 percent. At 12 months post-hatch typical sizes are 10+ kg and 110+ cm. Apart from the weaning phase, where survival might only be 75 to 85 percent, typical mortality losses in the other production phases are less than 5 percent. And, unlike many comparable species, grading does not seem to improve the overall performance of Arapaima during grow-out.

Many ecto- and endoparasites have been documented under typical farming conditions, but several common therapeutic compounds used on other cultured fishes can provide some level of control. Additionally, a number of bacterial pathogens may attack Arapaima at various stages of the production cycle. Growers typically have limited resources and try to minimise stress and practice biosecurity to the greatest extent possible, rarely utilising antibiotics.

Although most aquaculture production to date has relied on pond- and cage-based culture with comparatively low levels of technology, Arapaima show impressive potential for use in RAS production. Their affinity for crowded conditions can provide more flexibility in efficiently utilising carrying capacity, and their rapid growth means more production cycles to recover investment costs (a key consideration in capital-intensive RAS). In a study confirming the fish’s adaptability to a variety of conditions, Pedrosa et al. (2019) evaluated a number of feeding strategies for juvenile Arapaima in RAS and reported comparable growth rates for all strategies.

© Alvines de Paiche San Martin

An authoritative perspective

Adriana Ferreira Lima, from Embrapa in Brazil, who is one of the most prolific researchers working with Arapaima, explains that research into Arapaima aquaculture is making slow, but steady progress.

“One of the key challenges remains the controlled reproduction of the species, which is essential for the sustainable development of its aquaculture. However, important advancements have been made in this area. Notably, the use of molecular markers for sex identification of broodstock has been a significant step forward. This service is now available to farmers through our institution, helping improve broodstock management. Additionally, progress in in vivo semen collection represents a crucial step toward the potential development of induced reproduction techniques, which could further enhance breeding success in captivity,” she reflects.

However, she also points to a number of other challenges to overcome, noting that: “One of the main demands is for a nutritionally-optimised formulated feed that can improve feed conversion ratios and reduce production costs. Although there is substantial knowledge on the nutritional requirements of Arapaima, the limited demand for formulated feed in many regions of Brazil has hindered the development of better commercial diets.

“Another major challenge is the availability of pathogen-free juveniles. Farmers not only struggle with fluctuations in juvenile supply due to reproductive constraints, but also face high mortality rates caused by diseases. Ensuring a steady and healthy supply of juveniles could significantly reduce production costs, as juvenile acquisition represents approximately 25 percent of operational expenses.

“To address these issues, our team is actively working to improve Arapaima reproduction by evaluating hormone applications, optimising broodstock nutrition, and refining management practices. However, due to limited research funding for this species, we have stopped our studies on disease control and nutritional requirements, despite their critical importance for improving production efficiency.”

© Greg Lutz

As far as the prospects for the industry, Ferriera Lima provides a realistic assessment, explaining that: “The biggest challenge for the Arapaima industry is achieving consistent production volume and market stability. A past initiative in Brazil demonstrated the potential of a vertically integrated system, where an industry player guaranteed the purchase of farmed Arapaima in a specific region. This model included the provision of juveniles, feed and technical support, ensuring market security for producers. As a result, Arapaima production increased significantly, highlighting that structural organisation—rather than just technical constraints—plays a major role in the industry's success.

“While advancements in technology for reproduction and production remain essential, the lack of coordination among farmers and industry stakeholders remains a significant barrier to the sector's growth in Brazil. Overcoming these organisational challenges, alongside improving access to key inputs such as juveniles and specialised feed, could unlock the industry's full potential.”

She also shares some insights into possible ways that the industry could progress.

“One of the main opportunities for Arapaima production lies in diversifying the species cultivated by farmers in Brazil, where aquaculture is predominantly focused on a single species. Additionally, there is growing interest in integrating Arapaima at low densities within tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) culture systems. This approach has shown potential for controlling opportunistic species in ponds, offering an alternative production model for Arapaima. Given the large number of tambaqui farmers operating in semi-intensive pond systems and facing challenges with unwanted fish species, this integrated system could provide both ecological and economic benefits. While our team has not yet studied this strategy in depth, it is a promising avenue for future research,” she explains.

Clearly, the road to widespread commercialisation will be challenging, especially with limited funding for much-needed research. But the unique features of Arapaima and the dedication of the many research groups working with it suggest it might just be a matter of time before consumers in many countries are familiar with this fish.

© FAO Open Knowledge