Fed aquaculture accounts for less than a third of Chinese seafood production - which is still dominated by capture fisheries, carp and molluscs - in part due to China's reluctance to import more soy and marine ingredients © Nocera

So explains Rabobank’s Gorjan Nikolik, who has calculated that the country – which was once one of the world’s biggest seafood exporters – is likely to have a $10 billion seafood trade deficit by 2030.

Precisely how they are going to make up this shortfall needs to be considered, he reflects.

Dire demographics

As Nikolik highlights, thanks to a dramatic decline in China's birth rate – from over 6 children per woman in the 1960s to 1.09 per woman today, the country is about to experience a decline in its working population, coupled with an increase in the median age from 29 in 2000 to 52 by 2050. As a result, the number of people over 60 is expected to reach 510 million by 2050 – the equivalent to the entire population of Europe and the UK combined.

Meanwhile continued urbanisation, with the urban population projected to increase from 550 million to 1.1 billion by 2050, is expected to drain on the rural workforce, reducing the numbers of people willing and able to work low paid, physically demanding traditional seafood roles.

“Ageing, urban people are unlikely to be working in a seafood processing plant or a fishing vessel or aquaculture operation. But they're very likely to be quite concerned with their health and trying to eat more lean and healthy food, including fish,” Nikolik points out.

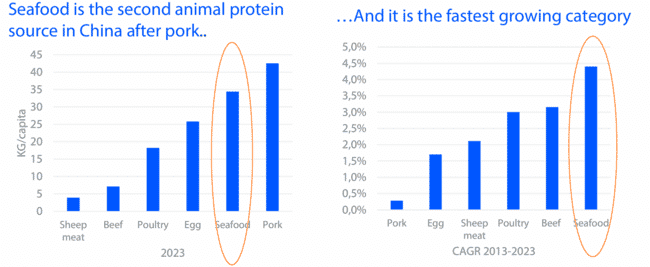

As seafood is considered the healthiest protein in Chinese culture, annual growth rates are forecast to remain high.

“Citizens in urban areas are not only richer, but they also have much better logistics, so have much better availability of seafood. If you combine this with the natural tendency to consume fish in China, this is a really important factor to realise,” Nikolik observes.

“In Chinese medicine and Chinese culture, fish is seen as the healthiest protein. And if you follow the growth of each protein category, there’s a direct correlation to what’s considered healthy in Chinese culture. Seafood is the second largest protein behind pork, and it's the fastest growing protein sector,” he adds.

Yet, while pork sales are stagnating, seafood demand continues to rise © MARA, NSB and RaboResearch

Chinese seafood production

In terms of production, Nikolik expects a decline in the three largest domestic sources of China’s seafood – capture fisheries, carp farms and mollusc farms – which cumulatively account for over 50 million tonnes annually.

“In the wild-catch sector, the government is pulling away from subsidies due to sustainability reasons, and they are closing some fisheries in lakes and rivers. When it comes to carp, the biggest problem is the lack of labour in the rural areas. And in the mollusc world there’s very limited additional space on the coast to expand,” Nikolik explains.

Meanwhile, while he does see high and mid-value fed aquaculture growing from its current level of around 16 million tonnes a year, he notes that challenges in feed supply, particularly fishmeal and soy imports are likely to limit this growth.

As a result, Nikolik suggests: “I would argue that China’s overall seafood production probably experience between 1 and 0 percent growth, or even start to decline gradually.”

A new world order

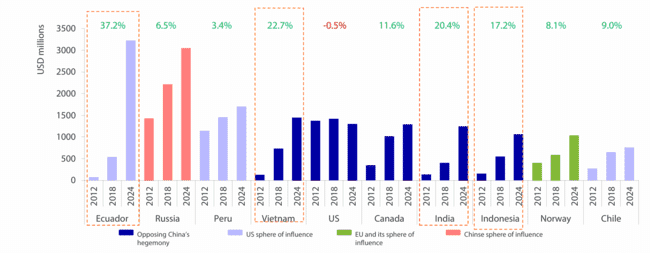

As Nikolik points out, China’s seafood trade balance has been declining by about $1.4 billion annually since 2014 and the country is projected to import $29 billion worth of seafood by 2030, with a $10 billion deficit.

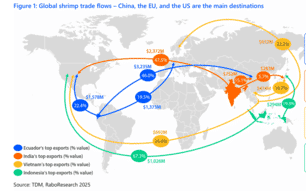

The country’s quest to make up for this shortfall is likely to be swayed by the polarisation of politics between those nations which predominantly fall under the US sphere of influence and those which look towards China. In a hypothetical scenario analysis of further escalating tensions between China and the US, he points out that most of the countries that China currently sources its seafood from are not likely to be within its sphere of influence.

“If you look at the top 10 countries that China imports seafood from, only Russia is part of their geopolitical sphere. And, hypothetically, if there’s a serious conflict between the US and China, those that currently fall under the US sphere of influence, like Chile and Ecuador, are likely to be forced to curtail or reduce their trade with China – you're already seeing that in Panama,” Nikolik reflects.

However, China appears to have anticipated such potential issues, and Nikolik suggests that might be why it’s opened its seafood market to countries like India, Vietnam, Ecuador and Indonesia – which have traditionally be wary of China’s growing influence.

Other than Russia, none of them currently have close ties with China, but that might change © Trade Data Monitor and RaboResearch

Conclusions

Food and energy are China’s two most vulnerable supply chains. And, although seafood may not be a top priority for President Xi – who is thought to have greater concerns over supplies of staples such as soy and rice – there’s no doubt that seafood trade will have an influence on the US/China power dichotomy.

As Nikolik concludes: “To put it all together: China’s seafood consumption will likely go up; in terms of production there’s a dilemma – because if they increase it, they will have more dependency on imports of fishmeal, fish oil and soy, which they don't want. The net is going to be that imports will need to increase considerably. And, in our opinion, China will import from parts of the world where they would like to increase their geopolitical influence – with a focus on Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America.

“China wants to become a more viable alternative to the US by increasing its trade. If the conflict escalates they will want to have as many allies as possible and opening their market is a good way of doing so.”