© Joshua Kettle, Unsplash

Shipwrecks and shellfish

The Benguela Current flows northward from Antarctica to the border between Namibia and Angola before veering starboard to begin its gyre. The upwelling off Lüderitz – feeding the waters of Walvis Bay – has long supported rich biodiversity.

In aquacultural terms, the country’s natural abundance hasn’t gone unnoticed and pioneers began experimenting with oyster cultivation in the 1980s.

Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) spat, which were originally imported from Chile, can now be sourced from hatcheries in Swakopmund and Lüderitz. A limited number of oyster growers - Tetelestai Mariculture, Nam Oyster, Fermar - use longlines and flip baskets in salt pans rented from Africa's largest producer of natural solar sea salt, Walvis Bay Salt.

It’s a mutually beneficial relationship: the salt company’s own research has shown that oysters help remove impurities from inlet ponds, making their salt refining process more efficient.

“The phytoplankton-rich water is pumped from the lagoon via an open channel, which also ensures proper oxygenation,” explains Linda Nuushona Lipinge, quality controller at Telestai.

“Spat measuring 2 mm grow to 40 g cocktail-size oysters in about six months, and to 70 g large oysters in eight months. Plump and flavourful, they suit a wide range of tastes, especially in the Chinese market. With a couple of additional months, they can reach jumbo and jumbo XL sizes,” she adds.

One major advantage of oyster farming along the Namibian coastline is the country’s limited number of rivers. Although in other parts of the world shellfish farming is often practised in estuaries, where nutrient-rich runoff feeds phytoplankton, river systems can also bring pollutants and pathogens.

However, the upwelling ocean currents mean that Namibian farmers don’t need to be near river mouths, while the absence of dense coastal cities keeps the ocean close to pristine.

© Tristan Macquet

A sulphurous relationship

But it’s not all roses and phytoplankton in the “land that god made in anger” – as the San people once described Namibia’s harsh environment.

No one knows this better than Henning du Plessis, one of the original oyster growers in Walvis Bay, who founded Telestai oyster farm.

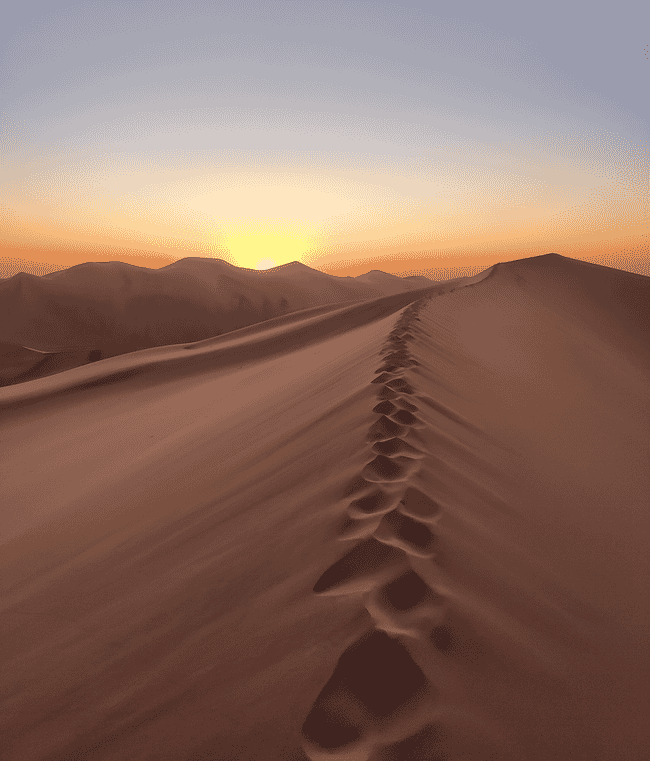

© Tristan Macquet

“I sold my shares in a fishing company and went all-in on oyster farming,” du Plessis recalls. “The Namibian government had just launched a major aquaculture initiative, and a dedicated farming zone was opened in the Walvis Bay lagoon. I started around 2006 with longlines and got early promising results. I had four million oysters in the water – 400,000 of them jumbo-sized, pre-ordered for the 2008 Beijing Olympics – and then the sulphur took everything.”

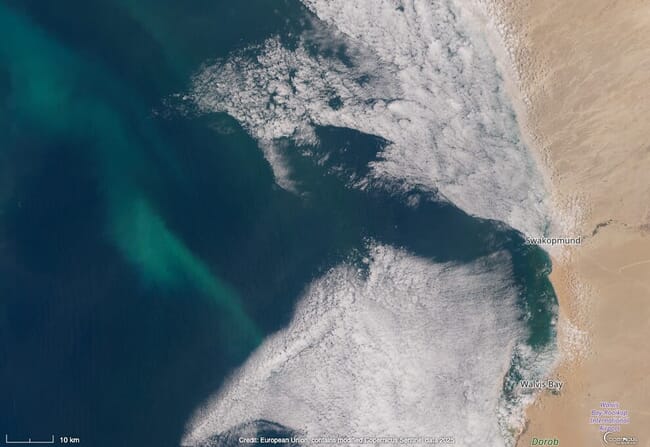

The bay’s immense productivity is also its greatest risk. Massive phytoplankton die-offs sink to the lagoon floor, producing hydrogen sulphide that builds up in the sediment. In the winter, the gas remains trapped, but come the rainy season (January–March), a reduction in atmospheric pressure and easterly winds allow it to rise through the water column, triggering a sulphur eruption.

As it ascends, the gas reacts with dissolved oxygen, forming sulphur oxides. The result is devastating: suffocation for most marine life, a sudden turquoise milkiness visible from space, and a pervasive smell of rotten eggs.

© European Union, contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2025

“Ninety-five percent of my oysters died in days. I went bankrupt. I salvaged what I could and sold the company to a fishing group – with the promise I’d find a way to keep the oysters alive,” du Plessis explains.

“My father worked in the salt pans – I knew they kept a few oysters there. Since water is pumped from the lagoon, it gives us early warning. Oxygen is monitored daily. When sulphur is detected, the oysters are relocated to Lüderitz for summering. Growth slows there, but they can be fattened again in Walvis Bay before shipment,” he adds.

This logistically complex solution helped to keep the sector alive. Tetelestai has since been acquired by a Chinese company, following the fishing group’s strategic refocus. Today, exports are mainly to China, Russia and South Africa, although there’s an increasing number of orders from Botswana and Zambia too. Meanwhile Du Plessis is now involved in a number of consultancies – notably with abalone hatcheries and fisheries. But oysters remain close to his heart and he believes that there are still ways to improve on the current system and space for new actors.

“There’s more to explore. Some clams survive the eruptions. Some species may be better suited to survive these conditions. Maybe we can adapt some French techniques of keeping the oysters out of the water to strengthen their muscles, allowing them to stay shut longer. We could also look at hatchery solutions or move back to the lagoon with mobile platforms, or floating systems that allow evacuation. IMTA could be another path – species like sea cucumbers could help reduce biomass accumulation in the pans,” he notes.

© Tristan Macquet

Are diamonds abalones' best friends?

Abalone farming is a growing industry in southern Africa. Washed-up kelp offers cheap feed for land-based systems, although energy and space remain limiting factors.

However, growing abalones in open waters has become increasingly risky, especially in South Africa, where speedboat-based pirates are known to raid farms and cash in on the staggering abalone prices in the Asian markets.

This is where Lüderitz may offer an unexpected edge. Isolated by hundreds of kilometres of desert on either side and hemmed in by De Beers' mining concessions, its location and restricted marine access may offer a natural safeguard, although it takes around four years to grow a 20 g hatchery juvenile into a market-ready 350 g adult.

Fisheries and aquaculture consultant Dave Russell, who has spent the last three decades in southern Africa, believes this sector is one to watch.

“If diamond-plated abalones aren’t your thing,” he smiles, “you may be more interested in the Norwegian–Namibian collaboration on offshore salmon, or in untapped value further up the processing chain.”

© Tristan Macquet

Beyond skulls and bones

“Fishing has always been productive here,” says Russell. “Before independence in 1990, Russian, South African and Spanish vessels used to haul over a million tonnes of fish a year. Some stocks have collapsed since, but Namibia has made efforts to introduce more sustainable practices. Still, one third of every fish is discarded.”

This isn’t bycatch, Russell explains, but anything not deemed commercially valuable – such as skin, bones and guts – that’s simply thrown away or vastly underutilised.

Yet these “side streams” could be part of the solution to one of Namibia’s most pressing environmental dilemmas: the growing push from mining firms to drill for marine phosphate. “The sediment is slimy,” Russell warns, “and disturbing it would likely release heavy metals.”

The risk isn’t theoretical. Walvis Bay oyster exports have already been paused due to alarming levels of cadmium, linked to nearby harbour dredging. And given Namibia’s vast uranium deposits, disturbing the seabed raises serious environmental concerns.

This is where Russell sees real promise: extracting phosphates from discarded fish bones and skulls could offer a safer, circular alternative. And with the recent launch of the Namibian Ocean Cluster – an offshoot of Iceland’s Ocean Cluster – he hopes the country will follow the path of Iceland’s 100 percent Fish and 100 percent Shrimp programmes. These initiatives aim to use every part of aquatic species to create a cascade of value-added products – from nutrition and pharmaceuticals to fertilisers and raw materials.

The opportunity doesn’t stop at fish. Namibia’s growing aquaculture sector is rich in underexploited potential: from abalone meat, shells and offcuts, to discarded oyster shells, to macroalgae biomass like the kelp cultivated by Kelp Blue in Lüderitz – all of which could feed into a local circular bioeconomy.

In Russell’s view, it’s not about reinventing the wheel, it’s about capturing more of the value that already exists. And in a country where “everything grows faster”, from oysters to seaweed, the real challenge is no longer growth, but transformation. Pick your species, unlock the process, and Namibia might just become the place to grow value from the sea.

© Tristan Macquet