Industry innovators such as Salmon Evolution are validating the benefits of HFTS © Salmon Evolution

So explains Rabobank’s Gorjan Nikolik, following the publication of a new report which makes a strong case for HFTS and might help rekindle faith in land-based salmon production.

“For so long we looked at RAS and they had two main shortcomings. The first is that the average cost level is very high, , and it is still not clear how the cost will come down if you scale up. Secondly, and most worryingly, RAS facilities have a volatile production, particularly due to the technical difficulties of operating a biofilter, while flow-though systems have much simpler technology,” Nikolik explains.

One of the biggest operating costs for HFTS is the energy required to pump in large volumes of seawater, but the success of players like Salmon Evolution has demonstrated that the high energy cost compared to conventional net pen farms is more than offset by the reduction in health treatments, the low mortality rates, the excellent FCRs and the impressive growth rates.

What’s more, while conventional farmers are experiencing regular downgrades of their fish, HFTS are hitting high proportions of superior grade fish, essentially giving them a premium on their products.

“Expectations had been that land-based salmon, given that it has such a low impact on the environment, should fetch a premium price. We always knew that that was going to be difficult to achieve but they are now getting a premium due to the high percentage of superior grade fish, which was an unexpected bonus,” Nikolik reflects.

What’s more, Nikolik notes that, in the high price environment of 2024, HFTS didn’t need to be at a large-scale to turn a profit.

“Salmon Evolution only harvested 680 tonnes in Q3 but were still has a positive operational EBITDA. And when they had a bigger quarter in terms of volume in Q1, during the peak of the winter ulcer crisis in conventional farming sector, they were the most profitable salmon farmer per kilo in the world. I would not have expected this to be possible until they had upscaled,” he reflects.

Another factor that interests Nikolik is that these systems can be used to produce market-sized fish, juveniles or both.

“That's the great thing about it because it gives you flexibility in the business model: you can have a faster cash cycle with juveniles, and from a bank perspective it changes the residual value,” he points out.

As a result, although Rabobank is yet to invest in a HFTS, Nikolik is keen that this new report encourages investors and lenders, including his own colleagues, to take note of the opportunity.

“We don't have any involvement yet, but we are talking to all the players and I think there is appetite from the bank to be a lender and potentially an investor or play a role in this sector in other ways like finding investors. A lot of investors still have a bit of a hangover from RAS, particularly in the US. I think this is a document that will help to separate the systems,” he observes.

© Rabobank

Geographical limits?

One of the main disadvantages of HFTS compared to RAS is that they need to be sited beside coastlines with water that’s consistently between 8 and 14 °C – which is the temperature suited to Atlantic salmon. As a result they are likely to be remain in salmon producing regions.

“For now it's really a Norwegian and Icelandic industry. The Norwegians were the pioneers and I think it's quite interesting to see that the Icelandic industry was the one who quickly adopted this, perhaps because they had natural resources like the lava rock that they can pump the water through, access to cheaper energy as well as a supportive government. But now the question is how and when will other countries have more interest in, because it can definitely work in Canada, in Scotland and in Chile, especially as there’s so much pressure both in Canada and Chile to preserve nature and make sure that the environmental impact is as low as possible,” Nikolik explains.

However, he is keeping an eye on Salmon Evolution’s next project, in South Korea, which could open up all manner of possibilities if it works.

“I think it's a very important move. If it’s successful, it will prove that this technology is transferable because it looks like it's going well in Norway and will probably will go well in Iceland. But both Norway and Iceland are fairly close culturally and have rich histories of seafood production, including salmon farming. But when you go to a region like Korea, you're not going to have access to local juveniles, you're not going to have access to local salmon feed. The whole infrastructure, the legislation, maybe the climate are all different. If they succeed then there too, then you're opening up the possibility for many more locations,” Nikolik reflects.

© Rabobank

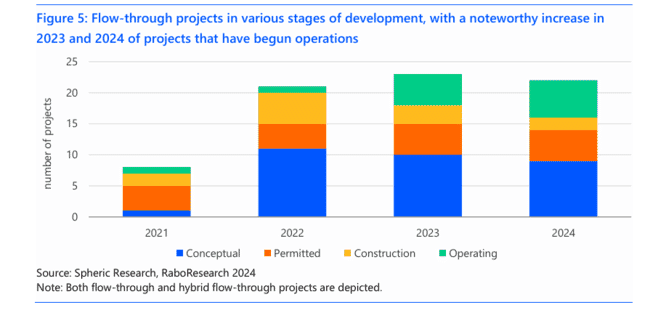

In total there are over 20 HFTS projects Rabobank is aware of. Of these some are operational at a low scale or under construction, while a similar number have got as far at the permitting stage or are still purely conceptual.

As a result, Nikolik gives a fairly conservative forecast for the sector’s growth, of up to 150,000 tonnes by 2030, and points out that this would make it a small but relevant proportion of the 3 million tonne farmed salmon sector. However, he thinks that it could grow much faster once it reaches critical mass.

“I think that once its gets to 100,000 tonnes they will have completely demonstrated its transferability and governments – not only in Chile, Iceland in Norway, but also other places – will see the low environmental impact and the good financial performance and start allocating licences. Capital would flow into it too,” he argues.

Interest from established salmon farmers?

Nikolik notes that the major salmon farming companies are yet to invest in HFTS, but believes that many are evaluating them, alongside several other options for grow-out expansion – notably offshore, closed containment and submersible net pens – while he thinks that RAS are likely to remain the industry standard for juvenile production.

“They've already made commitments to RAS for smolt production and it works and they think that a combination of closed containment and offshore could allow them to grow in the grow-out stage. But I think as HFTS become more and more viable, they will be more interested in it. The only question then is, whether it’s easier to get a licence for than it is to do RAS for the juvenile and then closed-containment for the offshore,” he explains.

“But I don't think anyone has ruled this out – unlike with RAS, which most salmon farmers were categorically against full grow-out in core markets, as it was too far from their business model to build RAS facilities in the US, or China, or Germany,” he adds.

© Salmon Evolution

The end of RAS?

Despite showing a more impressive trajectory than RAS, Nikolik doesn’t think that the rise of HFTS will mark the demise of the former.

“I think these two are completely different types of industry. I see flow-through as an addition to the traditional salmon farming industry, while RAS is a new industry that basically allows you to bring the seafood close to the customer and can still flourish with that model,” he suggests.

It also depends on species, with some – such as trout and seriola – showing better potential in RAS than Atlantic salmon.

“For Atlantic salmon you need scale, and as the incumbent industry is so vast it's very difficult for RAS to compete, at the current technology level. But I still think that if you're putting Atlantic salmon RAS in Japan or China or maybe even the US then maybe it could work, but it'll take longer and it will be more niche,” Nikolik asserts.

Regardless of the fate of RAS Nikolik is undoubtedly enthusiastic about the prospects for – and significance of – the emergence of HFTS.

“I think we cannot understate the importance of demonstrating that it's viable, because we've been working with the same business model in salmon for 20-plus years, and these systems are showing a different way of growing the sector and meeting the ever-growing demand for salmon,” he concludes.