© St Andrews

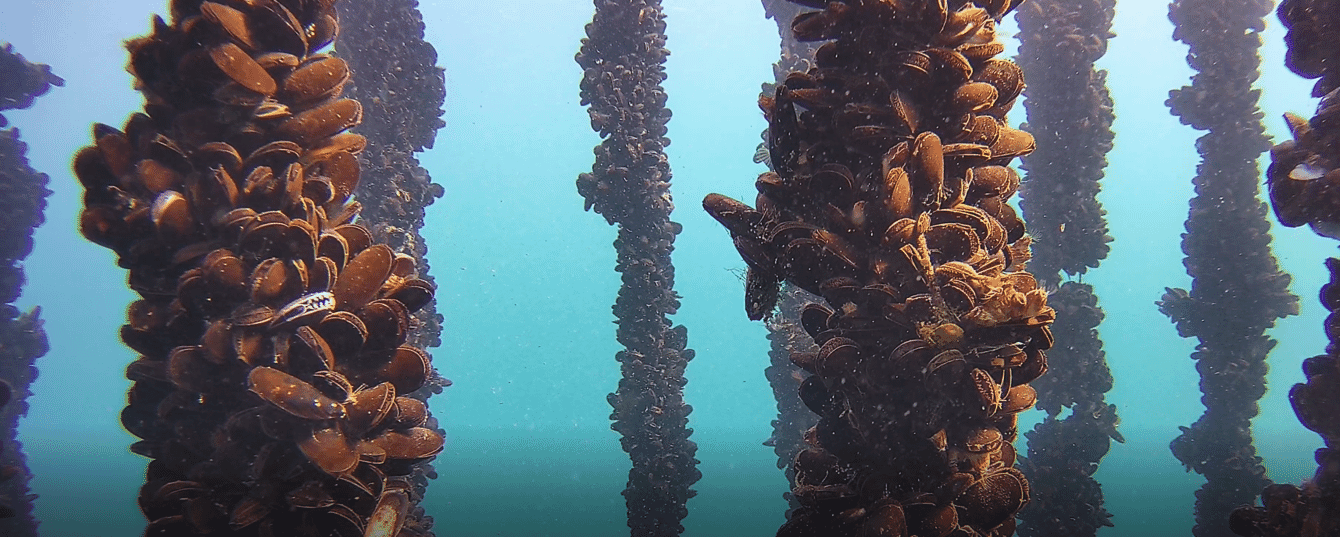

Chile’s mussel farming industry has been a huge success – growing rapidly from 25,000 tonnes at the turn of the century to 388,000 tonnes in 2023, with exports worth $292 million and 17,000 people directly employed.

“There have been three main factors behind the growth: the installation of processing plants for export of frozen mussels, new sites that were available and the opening of new markets, especially in Europe and Asia,” Howard explains.

Despite all the positives, recent years have seen a decline from the country’s 450,000 tonne peak in 2021 and Howard predicts that the industry will, at best, stabilise.

“It won't grow any more: there's no more market for the mussels and there are no more sites available. The only way to grow is to buy from somebody else and the price of a site per hectare is $13,000,” he explains.

“We don't get any recognition from the government. We don't know what was the reason behind it, but five years ago they said no more, that's it. Unfortunately, the environmental people are also making it more and more difficult to farm mussels. And the increase in production costs in terms of labour, fuel and spare parts, has not been reflected in the price of the mussels,” he adds.

Another factor is the growing recognition of the rights of the indigenous people in southern Chile.

“In Chile we have the ‘Lafkenche Law’ which, since 2008, has allowed indigenous people to claim large areas of the sea, which means that there are thousands of hectares where we can’t cultivate mussels,” Howard explains.

Despite these issues, the industry is still sizeable – second only to China and ahead of Spain, which was the traditional powerhouse of Western mussel production.

Covering a combined total of 11,500 hectares of leases, the Chilean sector’s epicentre is Chiloe Island. Of the 1,200 producers 77 percent harvest less than or up to 1,000 tonnes a year; 20 percent harvest between 1,000 and 5,000 metric tonnes; while 3 percent harvest over 5,000 tonnes. None are close to St Andrews’ totals.

Howard, who previously exported Chilean flat oysters to the US, then frozen Pacific oysters to the Asian market, joined St Andrews in 2006.

“At the beginning farming was done by hand using small barges, with most companies producing 300 to 500 tonnes. Nowadays farmers use hydraulic systems to seed and harvest and we find plenty of farmers producing over 1,000 tonnes a year,” he reflects.

“And, although there are still many family-owned and operated companies, we're finding out that young people don't want to work in mussels these days,” he adds.

© St Andrews

The St Andrews way

St Andrews has two processing plants and 69 growing sites, of which 49 are active, spread over 1,400 hectares, The company harvests 60,000 tonnes of mussels per year and Howard attributes their growth to the vision of the owners and their decision to build major processing plants that needed large volumes of mussels to make worthwhile.

“The owners visualized that the mussel is a great product and a cheap protein and with a great future. In order to be able to supply our own processing plants throughout the year, you have to have plenty of sites distributed in the different mussel areas,” he reflects.

As with all companies in Chile, regulations dictate that sites for collecting spat must be separate from those used for grow-out. Between them, the company’s grow-out operations have 2,160 x 100 metre long lines installed, which are all imported from New Zealand.

Howard oversaw the transition to the New Zealand system, which allows them to seed up to 48 km of long lines per day using barges.

Meanwhile the spats are collected on 4 m long nets – according to Howard St Andrews has a staggering 1,200,200 of these – and then peeled off via specially developed machines, before being seeded onto the longlines.

“We have two seeding platforms. Each will seed 48 km per day at a density of 900 seeds per metre – after a couple of years we found out that that's the best number because if the seeds are separated too much, we will get barnacles, which are a big problem for the industry,” Howard explains.

After 12-14 months, the mussels are ready to harvest at 14 to 20 g each and the company can harvest – and process – an impressive 560 tonnes per day.

At the processing plant the mussels are kept as whole shells, turned into half shells or have their shells removed completely. As there’s very little demand for shellfish within Chile, all varieties are then frozen using the individual quick freezing (IQF) technique, due to the lack of demand for fresh shellfish locally.

The majority of their produce ends up in Europe – a large market, and one that supported the rapid growth of the Chilean industry, but one that’s stagnated a bit in recent years. As a result, St. Andrews is keen to develop new options.

“We’re starting to develop North America. Most people don't eat mussels there and they need to be convinced, but we think that is a big market for the future. We also have Asia, while Russia is a very important customer of ours too,” notes Howard.

© St Andrews

Meanwhile there’s an increasing interest in some geographies for developing uses for the shells, which are packed with calcium carbonate, Howard says that options in Chile are limited – with most of them being heated, crushed and then used as fertiliser on farms on the Chilean mainland.

“Now we're trying to encourage the government to allow us to return the shells to the sea. The acidification of the ocean is quite incredible and we should be allowed to put the shells back. This year we’ve found plenty of cracked shells in our live mussels and we think it’s because of the acidification,” Howard explains.

Other challenges include the need to increase productivity of each site, given that it’s both increasingly expensive to operate existing sites and that it’s increasingly hard to find new sites.

“From a farmer’s point of view, we have to achieve 8 kg per metre of rope as an average – up from 6.56 kg per m – and get the collectors to yield more spat,” Howard argues.

Looking ahead Howard thinks it’s unlikely for his former employers to increase production substantially but he hopes that – one day – consumers will wake up to the health benefits of mussels.

“I don’t see St Andrews growing more than a harvest of 60.000 tonnes per year, but I would like more consumers to recognise that mussels are a healthy product which should be eaten at least once a week,” he concludes.