© Seaweedland

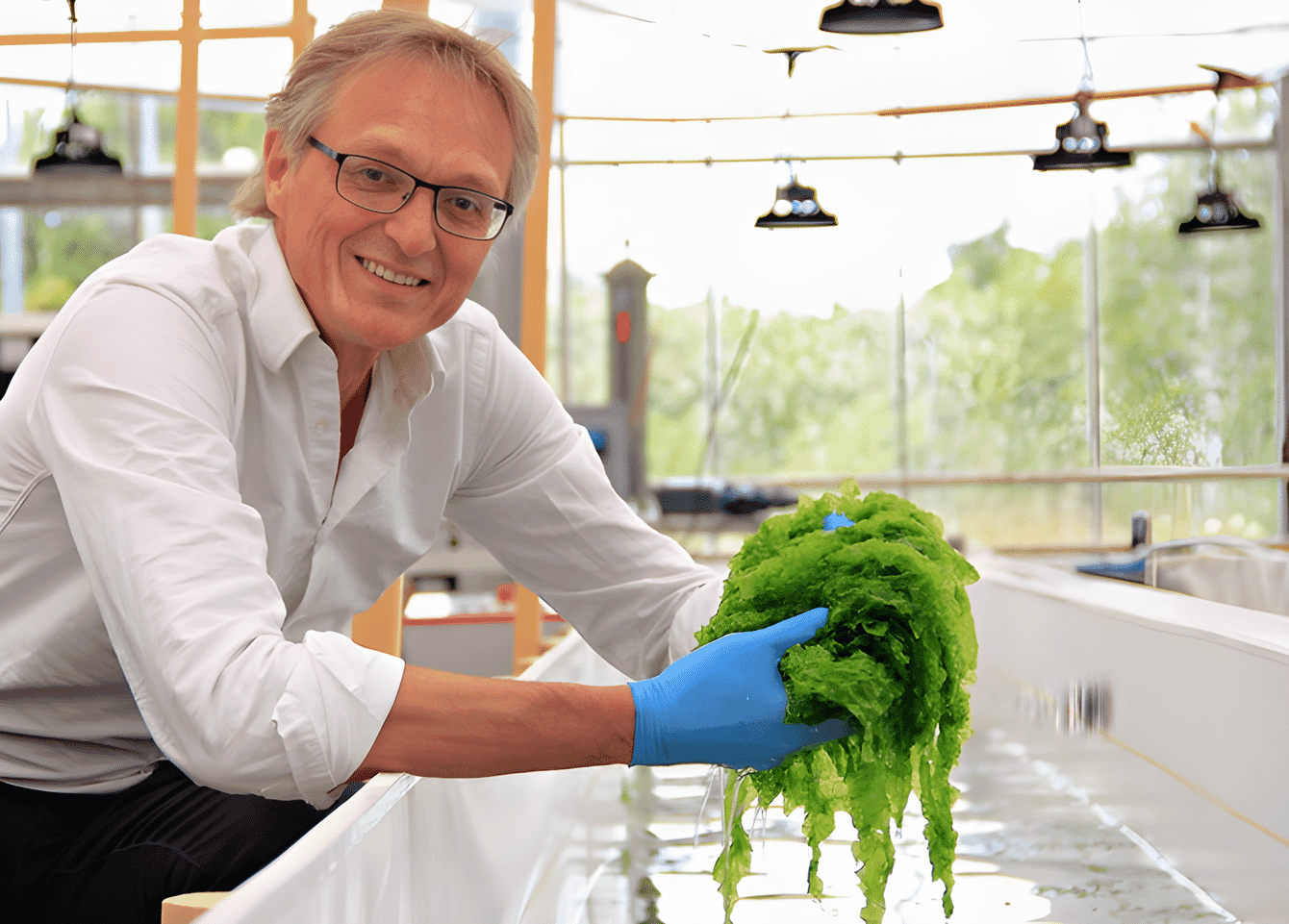

Seaweedland CEO Sven Rusticus didn’t see a lot of appetite for land-based cultivation at his first encounter with the broader seaweed industry at the Seagriculture conference in 2022.

“I heard a lot of sea-based operations talk about their struggles with quality, seasonality and predictability of their harvests and I thought, land-based can solve those issues really well. But when I aired my idea, everyone said, that won't work here, it's too expensive – you have to do it at sea. But that only motivated me more to do it my way,” he recalls.

Three years on, a 2,000 square metre pilot production site producing 2 tonnes of fresh seaweed a year has been set up next door to close collaborators Hortimare, the seaweed breeding specialists.

Rusticus is growing Ulva and Palmaria and his champion customer is De Librije, the only three Michelin-star restaurant in The Netherlands, but Rusticus has bigger ambitions.

“Restaurants are our starting market, but we don’t want to just produce for the happy few. We want to have impact, grow at the hectare scale,” he reflects.

To achieve that vision, Seaweedland first needed to work out how to reduce the cost of cultivation.

Reducing cultivation costs

Currently seaweed is sold to restaurants and universities between €20 and €80 per kg fresh, but Rusticus is confident that once production capacity scales to above 100 tonnes per year, sales prices between €6 and €20 per kg fresh seaweed are realistic, depending on the species and the local production cost. At higher production capacity prices will become even lower.

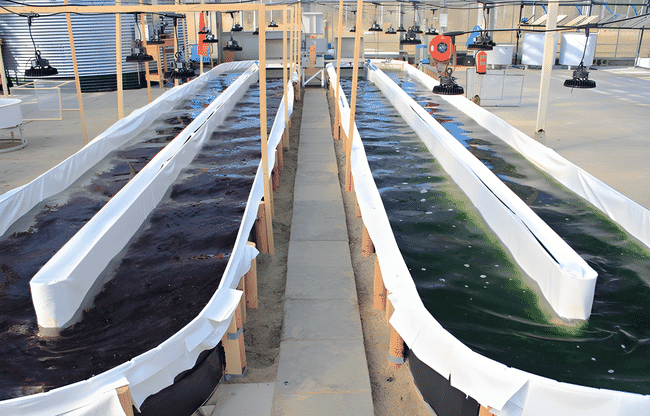

Taking advantage of the depth of knowhow and technology in indoor horticulture in the Netherlands, which is characterised by maximum environmental control, Seaweedland uses indoor raceway ponds.

“We started off with tumbling tanks, because that’s what everyone else was doing. But when we started calculating energy costs, it stopped making sense. You also need to build extremely precise, extremely level, otherwise you very quickly get dead zones without movement in your tank,” Rusticus explains.

Instead, Seaweedland was inspired by nearby AlgaSpring, a Dutch microalgae producer growing Nannochloropsis in 1.3 hectares of raceways under glass.

”We’re really just at the start of the development of raceway technology for the seaweed industry in my opinion. I really believe in that technology. There is a challenge in separating the weeds from the water to treat the water, that’s true, but we have made some technical breakthroughs there. Beyond that, measurement of all the variables is crucial of course. After working in the chemical industry at Shell and Akzo Nobel early in my career I didn’t use my degree in control and measurement technology for 25 years. Now I am returning to my old field of expertise by applying it to aquaculture,” Rusticus notes.

Beyond the pivot to indoor raceways, choosing the right location will be key to reducing costs, according to Rusticus.

“We’re looking at four locations in the Netherlands. The most likely option right now is a mine near Groningen that produces magnesium salt. It’s 30 km from the coast, and their salty wastewater is pumped into the sea. That water is extremely clean, consistent and free. We can also use waste heat from their factory and waste CO2 to supercharge seaweed growth,” he explains.

Rusticus’s vision is to build a three hectare farm containing a series of 100-metre long raceways that could produce up to 600 tonnes of seaweeds per year, at a low cost.

© Seaweedland

Hitting the hybrid meat market

To bring those volumes to the end consumer, Rusticus sees hybrid meat as an important segment where existing demand for seaweeds is poised to scale significantly, if supply can match the customers’ criteria.

“Meat producers and retailers want to reduce their foodprint, improve the health and also the taste and texture of their products. Seaweeds do all of that. We have letters of intent for 5 tonnes, 20 tonnes, even 100 tonnes fresh, several years from now. So we know the volumes and the prices customers are willing to pay. And those prices will give us a good margin,” he explains.

While other seaweed companies have advertised their products with seaweeds front and centre on the package, Seaweedland prefers a more subdued place on the package for seaweeds, as a functional ingredient, quietly helping in the background.

“For instance, one of our partners is Royal Smilde, whose sausage rolls are found in petrol stations across the Netherlands. Those sausage rolls already contain seaweeds today thanks to their joint venture with Seaweed Food Solutions. It’s not advertised as such. We won first prize together at the Dutch Butchers Trade Fair for a sausage with 20 percent dulse. We didn’t call it a seaweed sausage. We called it the Umami Sausage,” Rusticus notes.

But haven’t seaweed companies been struggling for years to break into the food market without success, citing low prices and lack of product-market fit?

Rusticus is quick to respond: “It’s a quality issue. We can ask more because we have a premium product. We deliver allergen-free, no crustaceans. That’s why food companies come to us. It’s the same for the vegan market: even if you wash your seaweed a hundred times, there will always be traces of crustaceans. So sea-based growers can’t get that label. We can. A price of €7-8 per kg for fresh Ulva is very realistic. For dulse prices are higher still.”

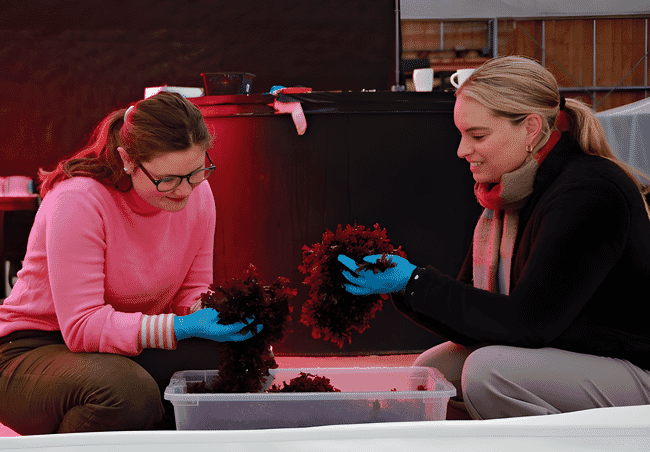

A lack of adaptability in terms of species is seen as the other key stumbling block for sea-based growers.

“We really look at the market, where is the demand coming from? In hybrid meat, they tell us no greens, few browns, we want reds. That’s a challenge for most European sea farmers, but not for us: we’re already growing dulse and testing Gracilaria and Chondrus crispus. The choice for Chondrus crispus came from a food company who needed a colourless product for hybrid chicken with high protein levels. Again, we can control the variables to grow higher protein levels, which you cannot do at sea and a special drying technique turns it white naturally when we want it to. Ulva is another really interesting species that’s more suitable to land-based cultivation, where demand is coming from its use as a taste enhancer and flavourful salt replacement,” Rusticus explains.

© Seaweedland

From Seaweedland to Seaweedworld?

Seaweedland’s goal reaches beyond simply growing macroalgae. Ultimately, it wants to develop technology that can be licensed to others, creating a network of farms that exchange data to fine-tune growing protocols and accelerate the seaweed industry’s growth.

”Seaweedland should become a network of land-based seaweed cultivation companies, based on the most advanced aquaculture technology. That vision is new. We want to take seaweed cultivation to the next level by collaborating in a franchise network,” Rusticus concludes.

© Seaweedland