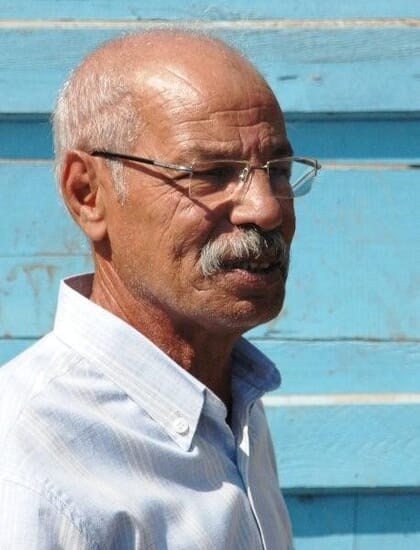

This series wouldn’t be representative of the true pioneers of African aquaculture without Egypt’s Ismail Radwan. From the late 1970s, he was one of a handful of Egyptians who developed unproductive, unused wetlands between Kafr El Sheik and the Mediterranean into the continent’s leading commercial tilapia producing region – providing daily, affordable, fresh food to millions, and also income and employment to thousands, across the Nile Delta. And in Ismail’s case, how he encompassed and then applied what he learnt about aquaculture from his studies and subsequent travels overseas across three continents to benefit so many people in his own country and the wider African aquaculture sector.

The early years

Ismail was born in Fayoum governorate and grew up in the 1950s and 1960s in a changing Egypt, first in Tanta, a growing city of 180,000, two and a half hours north of Cairo, then moving to Alexandria in his teens. His early schooldays in Tanta saw him particularly enjoying PE and gymnastics, and as a Boy Scout he was regularly exploring the fields of the Nile delta, where agriculture had been developing and intensifying to produce food for Egypt’s growing cities of Cairo and Alexandria.

He left school in 1963 to study at the Agriculture University in Alexandria, and then carried out his national (army) service between 1968-74, during times of unrest and upheaval in the Middle East. He first got involved in aquaculture aged 33, landing a job as a technician on a government-owned fish farm north of Kafr El Sheik, by 1979 becoming assistant manager. The 500-hectare pilot farm and associated hatchery were developed through FAO, working initially with common carp, then developing polyculture in ponds with tilapias and two local species of mullet.

In the 1980s Ismail joined forces with an existing fish farmer and businessman called El Hadad, on a brackish water site growing tilapias and mullet – the site he would eventually go on to own and develop himself into the Egyptian Aquaculture Center (EAC). In those early days the site met requirements of water first – having a good sub-surface groundwater supply (10ppt saline, with stable temperature and chemical characteristics), with some existing ponds and good land/soil profiles for further expansion.

The site was also close to local markets and input suppliers, including the young but growing fish feed sector. In those days Ismail recalls the government began a programme of reclaiming formerly non-productive wetlands for aquaculture, south of the brackish water Lake Barolus. In 1983 he benefitted from being sent to India and Thailand, for aquaculture exposure visits where he learnt about different species and their hatchery production and growout systems. This showed him how aquaculture and farmed fish were going to be hugely important in South Asia and wider afield over the years to come – particularly in Thailand, with tilapia being at the forefront.

Auburn days

In July 1985 Ismail’s life changed dramatically as through the Camp David Agreement he and 30 other Egyptians got the opportunity to study for master’s degrees in fisheries and aquaculture at Auburn University. Ismail used his time well at Auburn and through observing and learning first-hand from the then growing southern US catfish sector he picked up many principles and applications which he knew he could put into practice in his own country. In those days he was taught and mentored by some famous names who went on to have significant impacts not just on tilapia but global aquaculture production. Through their teaching and applied research, they continually reached out internationally to understand and learn about, then collaborate with, partners from Tokyo to Thailand, Cairo to Korea, and Mombasa to Manaus. Ismail particularly remembers Professors Lovshen, Brummett, Boyd, Rouse and Lovell to name but a few, and the simplicity and clarity of what and how they taught. Their research and work with tilapias, particularly hatchery and pond-based, from 40 years ago is still widely used today through teaching and extension around the world. Also, he reminisces how they taught their students to undertake true applied research:

“If you have an idea then go and test it scientifically and economically, in a hatchery or farm – then decide yes or no,” he recalls.

This very much shaped the way in which Ismail farmed fish for the following 40 years.

Back home

In 1988 Ismail returned home, his head full of ideas. He initially worked as an assistant researcher at the Abassa Center (now WorldFish), then enrolled for a PhD in agricultural extension at Mansoura University. But, unlike most of his colleagues returning from Auburn who went into academia and government positions, Ismail wanted to put into practice what he had learnt commercially. He began to do exactly this on the brackish water pond site with his partner El Hamed at the same time as studying.

On this site they further developed earthpond polyculture of tilapias and mullet, and Ismail designed and developed a hapa-based monosex tilapia hatchery from what he had learnt in both Auburn and Thailand. In the 1990s the site grew to 70 ponds, with initial harvests of 3 tonnes per hectare, each 6-month cycle. And although at significant cost they were able to install a mains electricity supply for the farm. By 1991 the hatchery was producing and selling 5 million monosex fingerlings per year, while around them the reclaimed wetlands were rapidly being transformed into commercial fish ponds for growout of tilapias and mullet, for as far as the eye could see.

Between 1995-2000, as demand for fingerlings rose, over 200 commercial monosex hatcheries were built throughout the region, each producing millions of fingerlings annually, many based on Ismail’s original designs and operational model.

Growth in production was accompanied by the scaling-up of the commercial feed sector, especially extruded, specially formulated feeds for tilapia, and the development of local feed mills which led to improving feed conversion ratios (FCRs) further benefiting fish farmers. Ismail describes these as the “golden years” when there was high, unmet demand for farmed fish in the surrounding governorates where market prices for harvested tilapia were roughly 11 Egyptian pounds (2.0 USD) per kg and the farmers were able to buy reasonable quality fish feed for just 1 Egyptian pound (0.10 USD) per kg –– less than 10 percent of the fish market price – thus generating significant profits, which were used to build more ponds, hire more staff and sell more fish.

The new hatchery and farm

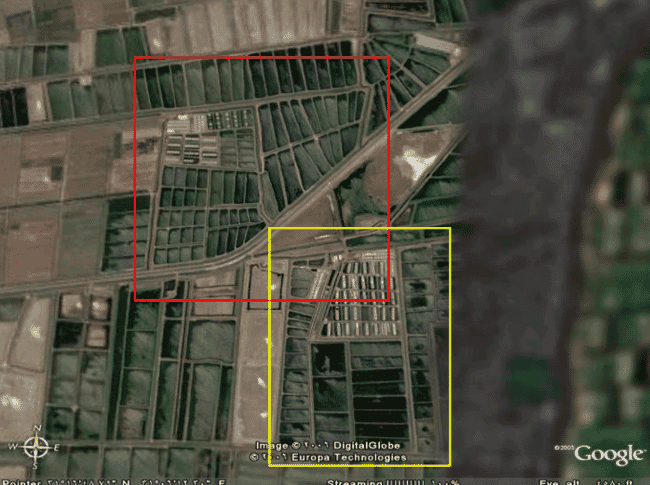

During these golden years by 1998 Ismail was able to buy and take over ownership of the farm he had worked on for so many years. In the same year he further expanded, constructing more ponds and upgrading the hatchery. However, before a spade had been put into the ground for further expansion Ismail reflected carefully on his previous experiences and adapted and designed the new farm from all he had learnt, modifying existing designs from previous farms he had worked on, always with the view of equating farm design to its efficient operational, financial and environmental future sustainability.

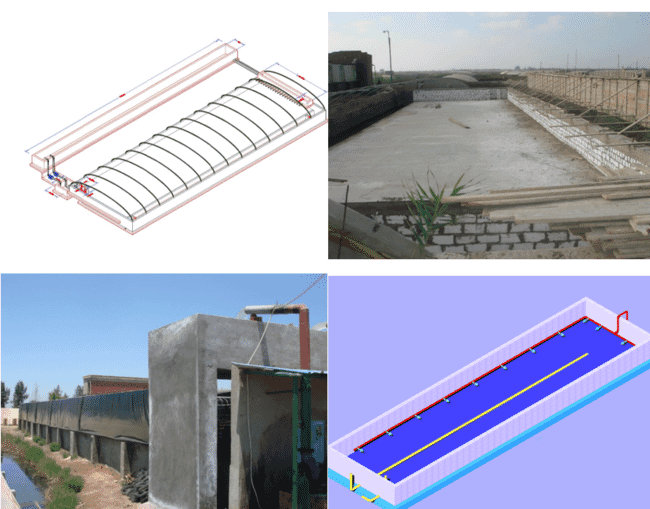

New ponds were constructed using an excavator and the hatchery expanded in concrete block modular design, covered by removable polytunnel structures which maintained temperature during the cooler winter months, allowing out-of-season production and the nursing of fingerlings. These also covered innovative, concrete raceways/channels within earthponds where grow-out stocks could be maintained at higher temperatures then sold to generate cashflows during the winters.

In those early years Ismail remembers certain equipment he bought being crucial to the running of the farm - a tractor, small truck and generator - which he says are still in day-to-day use 20 years later.

© Google Earth

New ponds were constructed using an excavator and the hatchery expanded in concrete block modular design, covered by removable polytunnel structures which maintained temperature during the cooler winter months, allowing out-of-season production and the nursing of fingerlings. These also covered innovative, concrete raceways/channels within earthponds, where grow-out stocks could be maintained at higher temperatures then sold to generate cashflows during the winters.

The birth and development of the Egyptian Aquaculture Center

For the next eight years Ismail ran and developed the farm business – firstly working towards financial viability and then making a profit. The farm and hatchery annually produced 70 tonnes of tilapia, 6 tonnes of mullet and between 3-5 million sex-reversed tilapia fingerlings from 6 hectares of ponds. Ismail also wanted to put back what he had learnt from others, and always had plans for setting up a training and research center alongside the running of a commercial hatchery and farm.

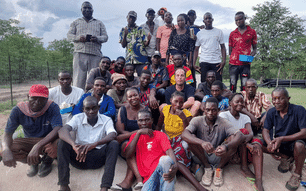

Therefore in 2006, once the farm was financially secure, he set up the Egyptian Aquaculture Center (EAC), adding purpose-built lecture, practical and residential facilities for on-farm training and applied research. By then there were eight full-time and three part-time staff (five farm and hatchery workers, one driver, one gardener, one mechanic, one electrician and technician, and one housekeeper). In the early years on-farm training programmes were primarily for Egyptians. However, as Ismail’s renown and networks widened, he was invited to various international events as a role model for the growing Egyptian aquaculture sector, including the Fish for All Summit in Abuja Nigeria in 2005, and from 2010 as part of a JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) team in aquaculture development and training in Benin. As a result, the EAC received many other African and wider international entrants for residential, hands-on training courses.

Ismail also developed a series of on-farm working internships where pre- and post-college students (including from the US) would come to work on the farm and hatchery over the summer to gain valuable experience. In 2008 he hosted many delegates from the International Symposium of Tilapia Aquaculture (ISTA 2008), held at the Center, giving them practical demonstrations of the various activities and operations around the farm (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zOXK7ZTPWqQ ).

And, not forgetting the words of his Auburn lecturers, Ismail encouraged and built up on-farm research at the EAC with commercial and other organisations – including trials for feed, equipment and genetics companies – with Ismail always keeping innovation at the heart of any of the subsequent changes made on the farm. One of these was the design and construction of a purpose-built, low-cost RAS system for nursery and growout of tilapias, at a time when water and water quality was becoming an increasing challenge for tilapia farmers across the delta. The final design included blockwork rendered tanks, a trickle-down filter made out of stacked, drilled local plastic drinks crates, opposing flow inlets and an outlet solids removal system.

Further details of these systems can be found at (https://www.sarnissa.stir.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Development-of-RAS-grow-out-systems-tilapia-Egypt-Radwan.pdf )

Present and future

After a lifetime working in aquaculture and watching an industry develop and evolve in his country Ismail believes that: “For the future of Egyptian aquaculture we need to look for other species (for instance shrimp) and develop other techniques to be able to compensate for the decreasing margins and to be able to add value to the now traditional tilapia crop.”

He also sees additional processing of tilapia as another promising option, as well as shortening the market chains from the fish farm gate to the consumer, by cutting out some of the intermediary traders.

Aquaculture in Egypt is now, according to Ismail, very different from the 1990s, with margins much reduced. Fish farmers are now paying 10-12 EP (0.75 – 0.9 USD) per kg for feed, while tilapia market prices are now 20 EP (1.5 USD) per kg, meaning that feed now accounts for around 60 percent of the farmers’ daily running costs.

In the last 10 years water quality and disease have also significantly affected Egyptian tilapia farmers, with some ploughing back their ponds to use for crop production. This irony does not escape Ismail, as it follows similar patterns he sees in the southern US catfish sector, where all those years ago he learnt his trade.

However, always positive and forward-thinking, Ismail believes declining margins and increasing environmental concerns have made those in the industry sit up, and to remain competitive and profitable realise they have to increase their own efficiencies, both in terms of production and in terms of the environment, so that they and their children will still be able to farm fish in years to come.

The author wishes to thank Ismail and his daughter Rabaa Radwan for their contributions and patience while writing the article. Thanks also to Randy Brummett for his help going back to the Auburn days and then what followed.

Ismail may be contacted at ismailabdelhamidradwan@gmail.com