As African aquaculture has evolved over the last 50 years, it is important for us all - both veterans and the up-and-coming - to acknowledge and recognise some of the special people who have had profound effects on its development.

Sadly, at the end of last year, we lost one of these true pioneers, Nick James, who devoted his career and passion towards African aquaculture - particularly in terms of hatcheries and indigenous African cichlids.

Its perhaps fitting we start with some words from one of his colleagues, which sums up Nick pretty well:

“Nick was really at his best when surrounded by fish. He would come alive in those type of surroundings, particularly if it gave him an opportunity to share knowledge with farmers who were interested in learning more about the species they were farming.”

The Fish Site published an article on Nick in 2020 when he was retiring from the famous Rivendell Hatchery, which he built and ran for over 32 years, so here we will not repeat too many of the details, but rather describe and celebrate his life.

The formative years

Nick was born in Lincoln, UK in October 1955, where his father was in the Royal Air Force and a lecturer at Cranwell College. Nick’s love of the water started when his father bought a 48-foot motor launch and converted it into a floating family home. By the summer of 1959, when Nick was only 4, the family sailed across to France and spent 18 months traversing across France’s canals and rivers to the Mediterranean, and then to Corsica, where they spent several months. Living on the boat inspired Nick’s fascination with fish and he often stored jam jars full of small ones he had caught in the cabin.

Towards the end of 1960 the family returned to the UK, but the English climate did not agree with Nick and he began to suffer badly from asthma. By 1966, despite further boat holidays in France, Nick's asthma was not improving. His parents decided a further move to a warm country and a new adventure was needed, so they packed up and moved to just outside Mutare - then Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe - where his father and mother taught at a boys' prep school. Nick was much happier and healthier, enjoying cricket and swimming in local rivers, and could often be found constructing dams in the stream at the bottom of the valley.

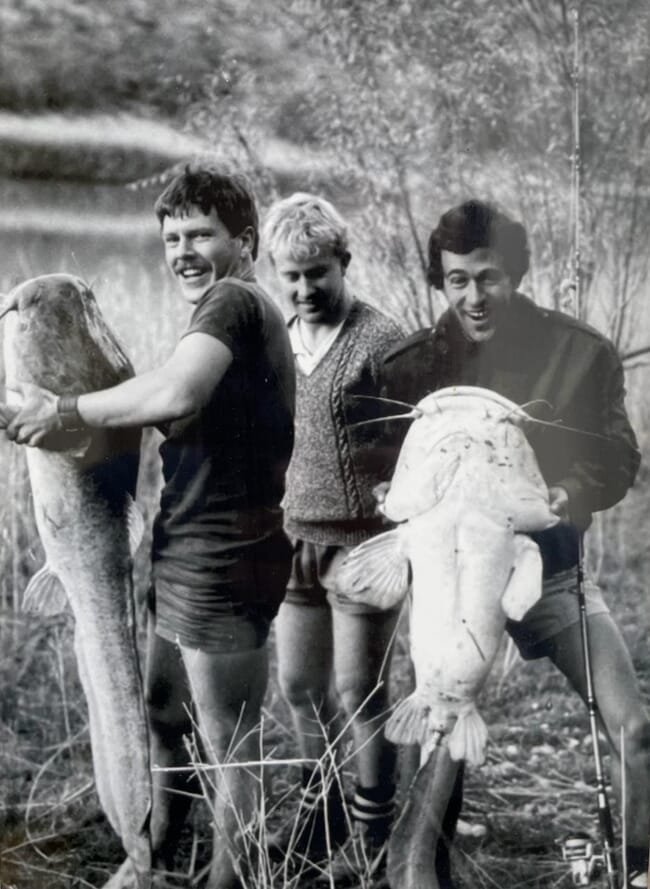

The family spent annual holidays on Lake Kariba in another boat Nick’s father had converted. At that time Kariba was one of the wonders of Africa. Nick loved sailing and fished with his father most evenings for bream (tilapia) and tiger fish, while Kariba and its magical sunsets taught Nick to love Africa – a love he never lost.

In 1974 Nick went to the University of Rhodesia to study geography, followed by a post-graduate teaching certificate. In 1978 he started teaching at Guinea Fowl School near Gweru. However, the bush war was getting closer and closer, so the family left Rhodesia and moved to Cape Town, where Nick found a position with Blue Star Line, negotiating ships’ entries and exits with the port authorities.

He enjoyed the work, but by 1982 began planning to start a fish farm with his parents. After considerable time looking for sites, they moved up to a small farm between Barberton and Nelspruit, in what is now Mpumalanga. Nick knew the importance of the water supply, and he spent the first years tirelessly digging small dams to create a gravity-fed flow supply for both the houses and the fish farm.

He started with carp and tilapia in basic tank and earthpond systems. In the early 1980s fish farming was just beginning in southern Africa. There were few, if any, hatcheries supplying fingerlings and no specialised fish feed producers. Also finding markets to sell the fish at competitive prices was difficult. However, despite some failures, these were hands-on learning days for Nick, which in later years he often said were vital for any successful fish farmer to go through.

In 1986 Nick moved down to Grahamstown where he joined the Department of Ichthyology at Rhodes University to do an MSc. On completion of his masters, he was offered a researcher’s position at the adjoining JLB Smith Institute of Ichthyology, which was at the time famous for its research on the coelacanth. His time at Rhodes made him realise he wanted to specialise in hatcheries and broodfish development. With this further knowledge and advice from faculty staff he shortly afterwards found the valley where his beloved Rivendell Hatchery was to be built.

A defining moment

In 1985 Nick found the hidden, empty valley with a broken nineteenth century dam, which he described as a real Shangri-La moment. He could see immediately the potential for renovating the dam and then being able to use the high-quality water specifically for hatching a range of cichlids and other species. He named the site Rivendell after JRR Tolkien’s famous home of the elves. The water supply was pristine and, even in the years of serious drought which adversely affected most of his farming neighbours across the Eastern Cape, Rivendell’s dam remained almost always full.

The hatchery was built using the hard-earned lessons from his first fish farming venture, combined with the skills he’d learnt at Rhodes. It was based round a series of polytunnels which allowed season-through breeding and manipulation of temperatures, so crucial for a commercial hatchery to be profitable. One room housed over 400 glass aquaria, whilst there were over 180 concrete tanks fed through different filtered RAS units, a solar heated breeding room, and four large polytunnels for green water ponds used for tilapia and Lake Malawi cichlids.

Nick also built two separate isolated facilities for sex reversal of tilapia swim-up fry and a conditioning section for fish ready for sale. Nick was always aware of the risk of disease transmission and took biosecurity very seriously, having strict protocols for not sharing equipment and water between sections, as well as disinfection when moving between them.

At its peak the hatchery was breeding and selling over 80 different species for the ornamental fish trade, including a range of Lake Malawi cichlids. For commercial aquaculture Nick bred and sold four Asian-developed strains of Oreochromis niloticus, two of mossambicus and also Tilapia rendalli (now known as Coptodon rendalli).

Rivendell steadily became known for the range and quality of fingerlings it produced. Most sales were within South Africa, but new markets and customers opened up in the USA, Mozambique, Swaziland (now Eswatini), Switzerland, and even South Korea.

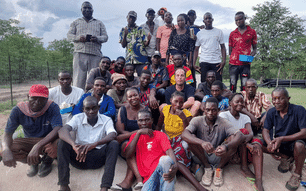

Despite the demands of building up his hatchery business, Nick also found the time to help set up many commercial fish farms in Mozambique, Zambia, Burundi, Botswana and South Africa. He did not believe in government or donor grants for building a financially viable African aquaculture sector, but rather in hard work, entrepreneurial innovation, and the use of designs and technologies appropriate for their surroundings.

In 2012 he became involved in the newly formed Tilapia Aquiculture Association of South Africa, and was elected onto its first executive committee. At that time, he was working and interacting with most of the early commercial tilapia producers in South Africa: including Lance Quiding, Frans Swanepoel, David Fincham, Valdi Periera, William Kelly, and Henk Stander and colleagues.

In those days there was considerable division of opinion across government, research and private sectors as to whether Nile tilapia should be an approved species for commercial farming in open waters. Nick was strong believer that they should be allowed to be farmed in more open systems to help reduce production costs per kg and spent a lifetime fighting for this, while providing a scientific evidence base to back up his opinions.

As one of Nick’s tilapia farming colleagues, Valdi Pereira, noted:

“I don’t think Nick’s deep understanding of what it takes to be successful at freshwater aquaculture was always properly understood or appreciated by policymakers – certainly not in South Africa. Despite this challenge it’s a testimony to his deep belief in the potential of the sector that he remained tireless in his willingness to become involved in local aquaculture projects that could showcase the contribution it could make to building financially viable livelihoods and contributing to food security.”

Nick had his own opinions but always worked towards providing an evidence base to inform both fish farmers and policy makers. In his later years he was invited back to the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (previously the JLB Smith Institute) in Grahamstown to run a nationwide survey project for mapping the country’s waters for the presence of Nile tilapia, something very close to his heart.

In 2019, aged 64, Nick decided to retire and pass on the hatchery to someone with the energy to take it to another level. Sadly, Nick didn’t see that day, but his words still reverberate about being a successful fish farmer to all of us:

“Be prepared to do everything yourself, be a fish farmer, a builder, a plumber, an electrician, a biologist and a business manager… only then will you be in any sort of position to tell others how it should be done… Be humble and not bombastic about your knowledge… getting your hands wet is essential.”

Acknowledgements

I would wish to thank Fran and Jacqui, Nick’s sister and daughter respectively, and other family members for their agreement and then help in writing this article. Also, to Valdi Pereira and Qurban Rouhani for their insights and fond memories of Nick.