© Victory Farms

Overcoming the fragmented nature of Kenyan land ownership – which is caused by the nature of the inheritance system – has traditionally been one of the most challenging obstacles for anyone looking to build an industrial-scale enterprise in the country.

However, Victory Farms – the country’s largest tilapia producer, with an 18,000 tonne target this year – are currently trialling a unique system for their egg production. One that is producing promising results.

“The biggest limit to our growth is fingerling production – our model is based on an extensive pond system for broodstock and egg collection, so to grow we need huge tracts of land,” explains Steve Moran, who co-founded the company, having previously helped to establish Tropo Farms as the pre-eminent tilapia producer in West Africa.

“The land gets divided and divided over generations: we ended up having to negotiate with 54 signatories to buy 12 hectares to establish our core farm,” he adds.

As well as the difficulties that this entailed, Moran also questioned whether establishing and expanding a single, fenced off site was the best way to do business, especially as Victory is based in an area where many people are living in poverty.

“We wanted to create a model that has multiple winners outside the fence as well,” he explains.

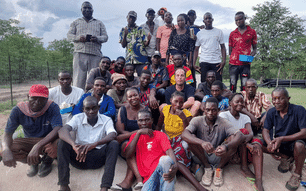

As a result Moran and co-founder Joseph Rehman decided to trial a radical alternative – outsourcing egg production to local farmers. The model, which is now known as the Homa Bay Extensive Aquaponics Programme (HEAP), is showing a great deal of promise.

“We find partners from within the community – we have a waiting list longer than your arm – and lease a plot of land from them. On each plot we put in a small broodstock pond – typically 20 x 60 m, with about 1,000 broodstock. Having built the pond we manage it as a Victory asset, while the landowner collects a monthly royalty, based on the volume of eggs we collect from that pond. That royalty alone averages out to about 2.5 times the minimum wage – pure passive income from a piece of land that’s been historically almost idle,” Moran explains.

.jpg?width=650&height=0)

The HEAP project provides Victory Farms with a stable egg supply, whilst partners receive a passive income © Victory Farms

Most ponds will be drained, disinfected limed and fertilised twice a year between generations, meaning that partner farmers will receive an income for 10-11 months of the year – bringing in much better income than the somewhat haphazard livestock and arable farming patterns that are characteristic of the area.

“Maybe every third or fourth year there would have been a maize or a sorghum crop, but generally there’s just goats grazing and soil degradation. We’re also using the effluent water from the ponds to irrigate land for vegetable production – hence why we term it extensive aquaponics,” Moran observes.

“Rather than normal aquaponics systems involving high value crops, which typically struggle to make any money, you now have tilapia produced in ponds, and effluent water from those ponds producing local vegetables for local consumption – tomatoes, onions, greens,” he adds.

The vegetable side of the business is being run by one of Victory’s sister organisations – Stable Foods – which runs the irrigation systems, either via a profit-sharing agreement or by renting the irrigation to the farmers.

According to Moran, around 30 percent of Victory’s eggs are currently being produced using the system, and he expects this to ramp up to 50 percent in the course of the next 12 months.

“It allows us the opportunity to grow our core business, and also to start selling our fingerlings to other farmers – meaning more people can use our genetics and it’s also creating winners outside of the fence. We’ve currently got 12 different partners in the pilot phase, which we initiated with support from Msingi, and we’re now working with USAID to scale it. We’re really excited as it’s unlocking incredible potential in terms of egg yield and fish production, as well as turning our bay into a bread basket for the region,” Moran enthuses.

Victory fills the ponds using solar-powered pumps and flushes each one regularly to ensure the water quality remains optimal for the tilapia. It is the flushing process that is used to irrigate the surrounding fields, thereby allowing for crop farming even in the dry season.

Water from the broodstock ponds is then used to fertilise and water fruit and veg in the surround lands, producing more food and more income for participating farmers © Victory Farms

“You take a product like tomatoes – in peak season people are dumping them and they’re rotting at the side of the road; in the scarce season they’re being brought in from halfway across the country and retailing for five times the price they would be in Nairobi. With this project you now have a consistent 12-month supply of affordable tomatoes. The same with onions, the same with greens – it’s all about enhancing food security and improving the nutrition in the local area,” Moran reflects.

Meanwhile, the company is also looking at ways to use the water from its core ponds to similar effect – pumping it to nearby fields rather than settling it in bioremediation ponds and then returning it to Lake Victoria.

“That way all the phosphates and nitrates that are in the water from the feed and fertiliser we put in the ponds produces veg for local consumption,” explains Moran.

The benefits of the system spread further than just the partner farmers.

“The landowners are the immediate winners, as they get direct cash, but they’re also employing people,” Moran notes.

Victory’s team will collect the eggs from each pond on a weekly basis, using a small mobile recirculatory system on the back of a pickup truck to transport them back to the main farm to be hatched and then on-grown

Given the increasingly high tech and biosecure nature of many aquaculture facilities around the world, this system of sending fish to – and bringing eggs back from – so many different sites, might come with risks. However, according to Moran, the benefits have – so far – outweighed any problems.

“There’s a slight risk of theft, but part of the agreement is that the landowner is responsible for security. The payment model allows for an acceptable level of attritional mortality but anything beyond that the landowner is responsible for. The good thing is that the fish are not seen as Victory’s fish, but as Alastair’s fish or Gladys' fish and – so far – we haven’t had any significant theft events from our partners’ ponds,” he reflects.

There is also a biosecurity concern related to bringing in eggs from external ponds, but the company is in the process of mitigating this with the installation of a separate RAS loop for any eggs that have arrived from partner farms.

“While, arguably, we have increased risk as we don’t control the external ponds, they are also diversifying that risk, as any challenge that occurs on the core farm would have the potential to spread much more quickly to adjacent ponds,” he points out.

As a result he’s keen to see the system rolled out more widely. And, given its advantages, so – no doubt – are many of the smallholder farmers around Homa Bay.