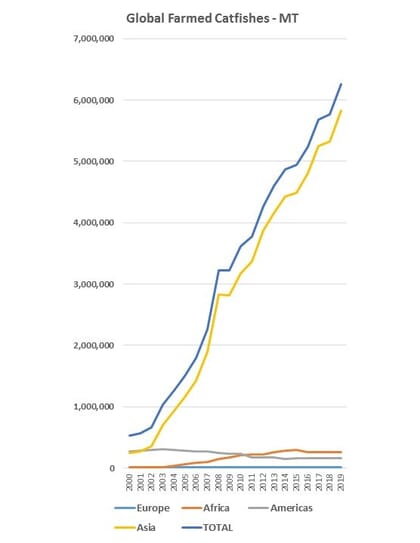

According to the FAO, although carps are still the most cultured group of fishes worldwide – over the past several years catfishes have surged past tilapia to take the number two spot globally.

However, the term “catfish” can mean different things to different people in different places. And that’s understandable since there are so many distinct species.

Taxonomists claim there are over 3,000 recognised species of catfish, and every year more are discovered and classified. They comprise the order Siluriformes, and can be found on every continent except Antarctica. It has been said that roughly one in every ten species of fish is a catfish, as is one in every 20 vertebrate species. The US government’s Integrated Taxonomic Information System recognises some 36 families of Siluriform fishes, and what makes a catfish a catfish actually has more to do with its skull and swimbladder than its whiskers. While there are literally thousands of catfish species and hundreds of potential candidates for aquaculture production, this article will focus on several that contribute the bulk of global harvests.

Channel catfish and its hybrid

The North American channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) was one of the first catfish species to be farmed commercially.

While federal hatcheries had been propagating the species since the late 1920s, the industry really began in the southern US in the late 1950s. It expanded from Arkansas throughout the Mississippi Delta and, as feed mills were established, acreage and harvests continued to grow. Eventually, the development of a number of processing plants across the region firmly established the industry as an economic force to be reckoned with. Most of the US industry has now shifted to the production of hybrids of channel catfish and blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus), and pond production methods are becoming more intensive.

The channel catfish tolerates cold winter temperatures and, as a result, it has been widely introduced beyond its natural range to far-off temperate countries in South America, Asia and Europe. In fact, from approximately two years of age onward it requires from several weeks to several months of cold temperatures to trigger maturation and spawning. In 1984 this species was introduced to China, where pond-based culture began in 1988 and exports to the US and elsewhere followed in the year 2000.

Channel catfish offered a novel alternative for Chinese fish farmers operating in temperate climates. Since 2010, Chinese production of I. punctatus has surpassed that of the species and its hybrid in the US. Over the past decade production in China has increased from slightly less than 200,000 tonnes to over 300,000 tonnes. Blue catfish were also introduced to China in the 1980s, according to reports from that country, but to date widespread channel x blue hybrid production has not occurred there.

Unlike some catfish species cultured in Asia and Africa, I. punctatus and its hybrid cannot utilise atmospheric oxygen, and therefore cannot tolerate prolonged or severe low oxygen conditions. Typical yields are 8 to 11 tonnes per hectare (ha) annually, but some intensive pond systems have been reported to attain harvests approaching 17 tonnes per ha.

Pangasius

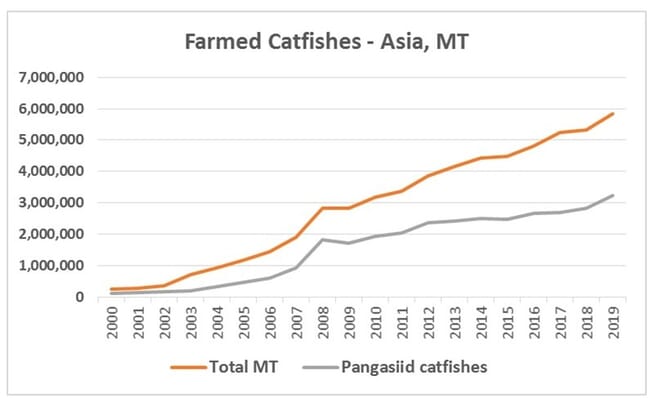

The Pangasiid catfishes are a closely related group of species found in Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries, the most widely cultured of which is Pangasianodon hyphophthalmus (formerly Pangasius hypophthalmus).

This tropical species is particularly suited for farming, as evidenced by the phenomenal growth of the industry in Vietnam over the past two decades. Although P. hypophthalmus had been cultured in Thailand since the 1950s, the first reported production from Vietnam to the FAO (40,000 tonnes) did not occur until 1997. By 2019, Vietnam’s reported production was 1.6 million tonnes. This growth trajectory is clearly what has propelled the rise of catfishes globally in recent years.

As was the case with channel catfish farming in the US, industry expansion in Vietnam and surrounding countries has been fuelled by the availability and adoption of manufactured feeds, as well as access to export-targeted processing facilities. P. hypophthalmus is increasingly being cultured in other Asian countries – including Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Laos and Malaysia. In recent years production has also been reported from several Caribbean nations, and the species has reportedly been introduced to Brazil and Colombia for farming.

A facultative air breather, which means dissolved oxygen levels are less important than for most farmed fish, the key consideration in successful culture of P. hypophthalmus is maintaining the other water quality parameters at acceptable levels. In most production operations in Vietnam this is accomplished by daily water exchanges of 20 to 40 percent. Production ponds are typically 4 metres deep, and yields are approximately 300 tonnes per ha per 6-8 month crop cycle (…that’s not a typographical error).

Clarias species and hybrids

Although there are several species of Clarias currently cultured throughout the world, the most recognised is probably C. gariepinus. Named after the Gariep River that delineates the southern part of its natural range in South Africa, the species occurs throughout most of Africa, the Middle East and northward into Eastern Europe. It has been described as having the widest range of latitude (some 70 degrees) of any freshwater fish. Thanks to its adaptability, C. gariepinus has been widely introduced to many countries beyond its native range – including Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Cuba, Nepal, the Netherlands and the Philippines.

Although interest in culturing C. gariepinus was already widespread in Africa and Europe by the 1970s, methods for reliable fingerling production were not developed until almost a decade later. As technical information and commercially available hormones have become more accessible across the African continent in recent years, fingerling availability is no longer a major barrier to the future growth of the industry, although fingerling quality remains problematic.

Some larger hatchery operators in Nigeria and elsewhere utilise intensive recirculating systems to produce high quality fingerlings in large numbers. However, fingerling supplies and quality are still cited as constraints to expansion of farming activities in many African countries. Since C. gariepinus is quite cannibalistic, fingerlings must be closely graded at stocking and at least once during the grow-out period.

While pond production has been the traditional method of culturing C. gariepinus, the species lends itself to high-density production in static tanks (with one to two water exchanges weekly) and also recirculating systems. This is due to the presence of an accessory air-breathing organ. While yields in static tanks have been reported as approaching 40 kg per m3 in a six month cycle (80 kg per m3 annually), those of recirculating systems can exceed 1,000 kg per m3 per year (with regular partial harvests).

As the standard of living increases and the number of consumers continues to grow, Africa’s catfish industry is expected to expand substantially in the coming decade. Increased availability of manufactured feed sources should help fuel this growth, as has been the case in other regions. Processing plants, however, are probably far off in the future for this sector, since traditional value chains are still sufficient to deliver fresh and smoked product to consumers in both rural and urban markets.

© B. Ganguly

African catfish production continues to attract investments from within the continent and beyond. A Czech company recently invested in a modern catfish hatchery in Cameroon, and the government of Tanzania has signed an agreement with the International Fund for Agricultural Development to support the annual production of 10 million catfish fingerlings at 15 development centres across that country. Numerous other projects promoting industry expansion are ongoing in many countries.

Another Clarias species, C. batrachus, is widely cultured in Thailand and the surrounding region. The range of this species apparently overlaps with the closely related C. magur and two possibly undescribed but distinct species or subspecies, from Bangladesh to Borneo. C. batrachus may be less cold tolerant than its African cousin, but it thrives throughout tropical Southeast Asia. Between C. batrachus, the introduced C. gariepinus and the native species C. macrocephalus in the Philippines, Guam and mainland Southeast Asia, a number of Clarias hybrids have been produced and cultured. C. batrachus was introduced in the state of Florida many decades ago and is now considered a well-established nuisance species there.

South America

A number of catfish species with aquaculture potential can be found in South America. Most are tropical, and many exhibit fast growth and are amenable to artificial reproduction.

© Estefeni de Jesus Pinto

The genus Pseudoplatystoma is already widely commercialised, and ongoing research is helping the industry advance rapidly. Recently, larval and juvenile diets for P. fasciatum were optimised by researchers in Peru. This species is important in several other countries as well, especially Brazil. Other related species of interest include P. reticulatum in Colombia and Venezuela and P. corruscans in Brazil.

A number of hybrids between various Pseudoplatystoma species and with Leiarius marmoratus are cultured, and these fish typically grow to 1.5 to 2 kg in 12 months. Hybridisation is relatively easy because artificial spawning methods have been well documented and are easily implemented. Pseudoplatystoma are more piscivorous than most catfish species, so their dietary protein requirements are comparatively high. Most production occurs in ponds, but these fish can adapt to grow-out conditions in raceways and cages, as well as recirculating nursery tanks.

The silver catfish, Rhamdia quelen, has been the focus of research and development in Argentina, Uruguay and also southern Brazil. This species appears to be more accepting of plant proteins. It is adaptable to a wide range of temperatures but it does best in mild, sub-tropical regions.

The future for catfishes?

As is the case with the carps, catfishes are a diverse group of species and many of them lend themselves to farming. And, as has been the case with tilapia and many other species, as commercial feeds become more widely available in places like Africa and South America we can expect to see more and more catfish aquaculture in these regions. Will these fish maintain their lead over tilapia? Will they eventually rival carps for global dominance? The trends suggest it may be possible one day.