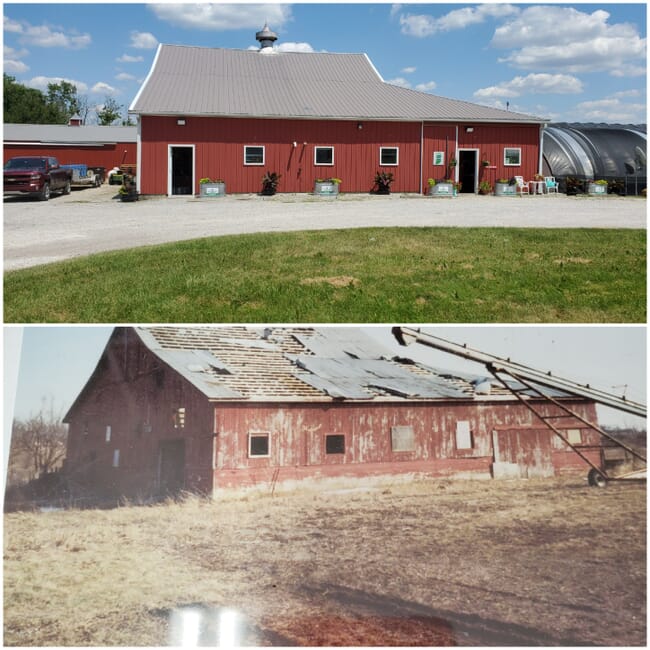

Brown co-founded RDM aquaculture, one of the first indoor shrimp farms in the US, in 2010 © RDM Aquaculture

Briefly describe your aquaculture career

It started in 2010 when I co-founded RDM Aquaculture and began working with shrimp. I thought there were hundreds of shrimp farms but later found out I had established the third indoor shrimp farm in the US. In the first two years, I was told it can’t be done and that I was wasting my time and money. Many said you can't raise shrimp indoors in a recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) but I’ve now been doing this for 12 years. It has been challenging, yet very rewarding at the same time.

What inspired you to start up a shrimp farm?

I completed my degree in fashion at Indiana Business College then worked as an interior designer for ten years and then had my son. I stayed home with him until he went to school. I wanted something the same hours as him that fit nicely with his schedule. Then I worked for nine years as a cafeteria manager. In 2010, my husband started the shrimp farm and I decided to give up my job and work there too. The best part was that I only worked three hours a day, finished by noon and drove 2 minutes to work.

Brown uses a biofloc system to raise Pacific white shrimp © RDM Aquaculture

What size is your farm and what species do you produce?

We run 19 production tanks, seven intermediate tanks and six to ten nursery tanks. We raise the Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) – the most common shrimp consumed – using biofloc or heterotrophic bacteria. Our water is 12 years old. The heterotrophic bacteria convert ammonia to nitrites to nitrates. In a way, it's allowing mother nature to do all the work of filter our water, just like the ocean takes care of itself.

We get shrimp post-larvae (PLs) that are ten days old and place them into nursery tanks for 25 days. We then move them, along with all their water, to an intermediate tank, where they go for 25 more days before entering the production tanks. We place 60,000 PLs every 25 days in the nursery tanks with new water. When the PLs come in, we acclimate them to 32 ppt saltwater. Then over the next week, we slowly add our biofloc from the production tanks to the nursery tank.

In the production tanks we divide them from 10,000 PLs to 3,500 PLs per tank. Once in production, we grow them out for 90 days for sale. By this time, the shrimp will have grown to 22 g each.

We did also raise crawfish in a clear freshwater system, and we did very well. But, for now, I have stopped because it takes 4 hours a day to weigh crawfish, and I did this seven days a week for four years. If I skipped a day, I would have about 40 dead crawfish in my tank [the larger ones will eat the smaller ones if not graded regularly].

Brown runs 19 production tanks, seven intermediate tanks and between six to ten nursery tanks © RDM Aquaculture

We also experimented with raising oysters indoors. We had a 50 percent survival rate then we made a mistake that killed them all. We're going to try that again in April of 2023. We originally started raising the oysters in the shrimp tanks, but they were not growing as well as we had hoped. We decided to move them to a clear saltwater tank where we conduct a water exchange every other day. And if we can master raising oysters, I would like to try other species moving on to scallops.

What have been your key milestones to date?

The first milestone was to have lasted more than one year. Our first year was awful. We lost a million shrimp during the first year and nearly a million during the second year. After three years, we did our first expansion by adding seven intermediate tanks. In 2017, we added 12 more production tanks, and we're looking at expanding again in 2023 with 24 more tanks.

We also were very successful with breeding and raising crawfish. Raising the crawfish was simple other than having to weigh them every day. If they were 1 g to 1.5 g larger than the others, the larger ones could kill the little ones, up to 10 a day. We had to keep the crawfish separated by size. We’ve designed a new system that will start in January, which we hope will reduce the procedure of weighing daily to once a week. In terms of raising oysters, we will have to try again next year.

How many tonnes of shrimp do you produce each year and what kind of production system do you operate?

On average, we raise 3 tonnes of shrimp per year. We sell on average 0.25 tonnes per month. We grow our shrimp in a RAS biofloc system, meaning that we use heterotrophic bacteria-based water, just like the ocean. We only use air to keep the water in suspension. Simple is best. We’ve no pumps or filters. We’re not replacing the water, not replacing that much salt, and the shrimp do fabulous. We have had our water for over 12 years.

RDM aquaculture raises 3 tonnes of shrimp per year and sells an average 0.25 tonnes per month © RDM Aquaculture

Are there any particular disadvantages using a biofloc system?

The only disadvantage is it takes about a year and a half to develop true heterotrophic bacteria. When you start out with the clear water tanks, you exchange all that ammonia and nitrites, and you get better survival rates.

Can you describe a typical day for you on the farm?

A typical day on our farm involves testing, feeding and cleaning the facility. Once a week, we move tanks and refill tanks. We conduct nine tests on the tanks daily. We test dissolved oxygen (DO), temperature, salinity, pH, ammonia nitrites, CO2, alkalinity and settled solids. We conduct four of these tests on a meter (DO, temp, salinity, and pH), do the settled solids with an Imhoff cone and the remaining test with a chemical reagent.

We spend the rest of the day on feeding because our old automatic feeders broke down due to the salt air. We move the water and shrimp if there are less than 5 pounds of shrimp left in a tank. This involves taking down all the water out of the tank by moving the water with a sump pump to a holding tank and then removing the remaining shrimp into the next sale tank. We will then clean the tank with water and a scrub brush. We put the water back into the tank and put the next batch of PLs into the tank. Occasionally, we offer tours as well to schools and the general public.

I have no desire to automate the tanks. Every tank has its unique ecosystem. Doing automation makes people lazy and not pay attention to the little details in the tanks. To give you some context, we visited a fish farm with a robotic system and noticed the alkalinity and pH levels were low, but the farmer didn't seem to care about the water condition. The next day, they ended up with dead fish as they weren’t paying attention to the water and how the fish moved. With automation, you rely on something else to tell you what is happening, and biofloc distorts the answer. The sad part is you aren't going to get high survival rates. You write down the numbers and don't look at what they mean. You have to know what your tanks are doing.

I hope to add 24 production tanks by the end of next year. I plan to do the tests hands-on on a Monday, which will take 4 hours with extra 24 tanks, every other day chemical tests and the rest on a metre, which takes about 2 hours. Once, I skipped four full days of testing and the next day came back to two full tanks of dead shrimp. The only problem is that their alkalinity levels had dropped. If I had caught it on the first day, all the fish would have survived. I cannot stress enough the importance of testing.

We rake the bottom of the tank, a task we never skip. We do this seven days a week. This consists of a small aquarium net attached to a 5-foot PVC pipe, which we use to rake into the dead spots to look for feed, dead fish, excess shells, and of course, to see the shrimp. The shrimp will dictate the condition of the water by their characteristics.

What are your main considerations to ensure the farm runs smoothly?

Our main concerns would be electricity and water quality. Without power, the shrimp will die in one hour. If their water quality is not up to standards, they become stressed and die.

Brown has found that indoor shrimp farming is possible, but it isn't as simple as people think © RDM Aquaculture

What challenges have you had to overcome to make your business economically successful, especially at a time of spiralling input prices?

In the beginning, it was challenging due to low survival rates. Once you get the bacteria at optimal levels, the survival rates will fall into place, and all that is required is the usual daily testing and feeding. Feed costs have gone up this year. We raise our shrimp for about $8 per pound and sell for $18 to $20 per pound.

What are your views on the rising popularity of indoor shrimp production in temperate regions?

It can be done but not as simple as people think. People tend to believe it's like having a fish tank at home. You throw in the fish and forget about them. Hopefully, they will live. There's work involved in raising this livestock. It's like any other livestock. People shouldn't chuck them in a tank and hope they survive.

What advice would you give to fellow indoor shrimp producers?

I would suggest giving it one year. Maintain your water at all times. If the water is brown and you don't see the shrimp, be sure to know what's happening. That's why testing the water every day ensures you understand how your shrimp are doing.

Do you consider yourselves true pioneers of indoor shrimp production and how have you managed to succeed when so many others have failed?

I guess we could be called pioneers. We made many mistakes in the first couple of years and stuck with them to make it a success. We didn't give up because things didn't go as planned. We continually test every day. And I think it makes a massive difference. Many people will disagree with me, but perhaps this is the reason we succeed. We never take water quality for granted. There isn’t much difference in raising shrimp, crawfish or any others. It's all about taking care of their water. That's why we call ourselves "guardians of water" and not seafood producers.

It’s been 12 years since RDM Aquaculture was established. How do you see the company evolving in the next 12?

We hope to have a go-to seafood facility in the next few years. We hope to have a seafood deli and restaurant, increasing our tourism and aquacultural production. By the end of 2023, we aim to have 24 more tanks. We want to expand by raising more species and offering fresh seafood choices for consumers. We’ve over-harvested the ocean. Our ocean needs a break. We hope to bring the ocean indoors to supply a great source of seafood without antibiotics, hormones or pollution. Then consumers can get good quality fresh food, free from chemicals and hormones. I have a lot of plans for our little farm. We aim to raise crawfish again and try the oysters again. If we succeed, hopefully, we can do an aquaponic system raising different vegetables too.