When wondering how Southern Africa’s tilapia sector could achieve exponential growth, David Fincham found inspiration in the poultry industry. He told delegates at the Association of International Seafood Professionals tilapia webinar series, Future of fish farming, that the poultry sector transitioned from a simple production model to an intensive model and exponential growth in 70 years. He identified specialised chicken houses as key to this expansion. Individual chicken houses can raise hundreds – or even thousands – of birds efficiently by optimising feed use, water use, stocking densities and health costs. So Fincham’s key question for the tilapia industry is, “how do we get to the chicken house scenario?”

He told delegates that the industry needed to identify the basic building blocks of tilapia farming – a set-up that would give producers consistent results in different environments. Taking this approach spurred the development of the “aquaculture production unit” or APU. Fincham’s APU is a single-tank system that can be housed inside a greenhouse structure. Single APUs can operate as a small-scale farm but since they are modular, farmers can purchase more units and scale their production. The systems are suitable for fishes’ different development stages – from fingerlings to slaughter weight. Fincham’s initial work with APUs across Southern Africa has been successful – and could be the system that lets the tilapia industry fulfil its potential as the “aquatic chicken”.

Fincham’s aquaculture experience in Southern Africa

Fincham has worked in Southern Africa’s tilapia sector for 35 years, and said that watching the industry progress has been, “an interesting observation.”

“Whilst the tilapia industry has grown exponentially worldwide, in Africa, the developments have been much slower,” he said. Most of the continent’s tilapia production is based on models that were developed by the Belgians and brought to the Democratic Republic of Congo 60 years ago. This production model emphasised pond farming and subsistence yields – commercial development wasn’t a high priority.

According to Fincham, Southern Africa’s commercial ventures have been comparatively slow to take off. Zimbabwe’s Lake Harvest was the first commercial cage farm on the continent. Other tilapia ventures have used Lake Harvest as a model for their own businesses and the farm’s personnel have been keen to share their expertise with other producers.

But building on Lake Harvest’s success has been difficult. Fincham told attendees that fewer than 100 commercial ventures have been developed in 30 years and that most of Africa’s tilapia is imported. The continent’s total population hovers at 1.4 billion – “at this pace of development, we’ll never produce enough fish to feed ourselves,” he said.

He wanted the industry to achieve exponential growth – and he looked at the poultry sector’s housing approach for inspiration.

What works with feathers could work with fins

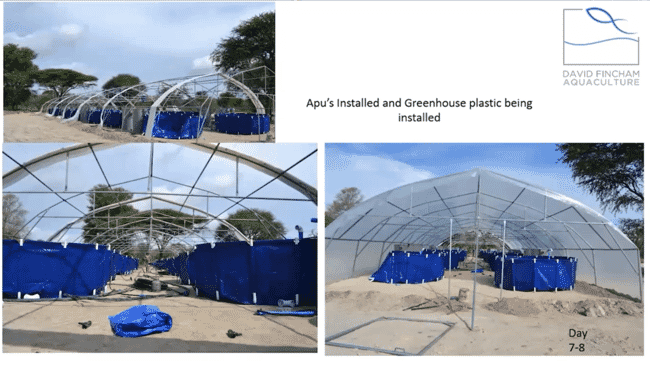

Fincham explained that the aquaculture production unit and greenhouse system was a tilapia farm’s basic building block. During a project in February 2021, Fincham and his team were able to construct a greenhouse in five days and install pre-assembled tanks shortly after. Individual APUs allow small-scale farmers to establish their operations and create low-tech ways to gain control over production. The APUs also develop farmers’ “wet hand” skills – the practical know-how and husbandry skills that can take farms from subsistence levels to commercial outputs.

Fincham said that the greenhouse emulates the temperature and environmental control capabilities in poultry barns. The set-up takes advantage of Southern Africa’s sunlight and heat, allowing farmers to keep tilapia at the optimal temperature for growth. This inexpensive “climate control” system gives farmers a longer growing season as well, making it easier for them to expand their operations.

Establishing APUs gave local communities an opportunity to develop skills and practices for commercial aquaculture. The modular and self-contained design means that the systems aren’t limited to rural environments either. Urban residents can establish an indoor unit or farm in developed areas, presenting an opportunity to, as Fincham said, “farm more fish in more places.”

APUs are also serving as research infrastructure for universities. Currently, there aren’t enough commercial farms where universities can conduct field research. APUs are helping address this gap, and giving scientists an opportunity to improve tilapia genetics, nutrition and health. The production research emulates the specialised work conducted in broiler chickens and egg layers – and will likely give the tilapia sector a similar production and efficiency boost.

As of 2022, Fincham has sold over 450 single APUs in nine different countries. He expects that APUs will gain traction in the future since the system, “creates more farms and allows fish to be farmed in more places.” As more communities opt for APUs, Southern Africa’s tilapia industry could achieve its goal of exponential growth and “[put] more fish on plates and [feed] more people.”

The Future of fish farming – tilapia series was held from 12 January to 26 January.

*Note - when this article was published on 11 February, the author said that Lake Harvest was operating in the 1980s. This is incorrect - Lake Harvest was established in 1997. We apologise for any confusion caused.

-

Preparing the site for the APUs and greenhouse -

Constructing the pre-fabricated trusses for the greenhouse -

Putting the trusses in the foundation holes -

Constructing the PVC ponds for the tilapia -

The indoor tilapia ponds and water filters -

The modular design allows multiple ponds to be added in the greenhouse structure -

Water supplies and aeration being installed -

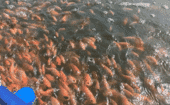

The tanks allow workers to develop their "wet hand" skills -

Tilapia at feeding time