© Rabobank

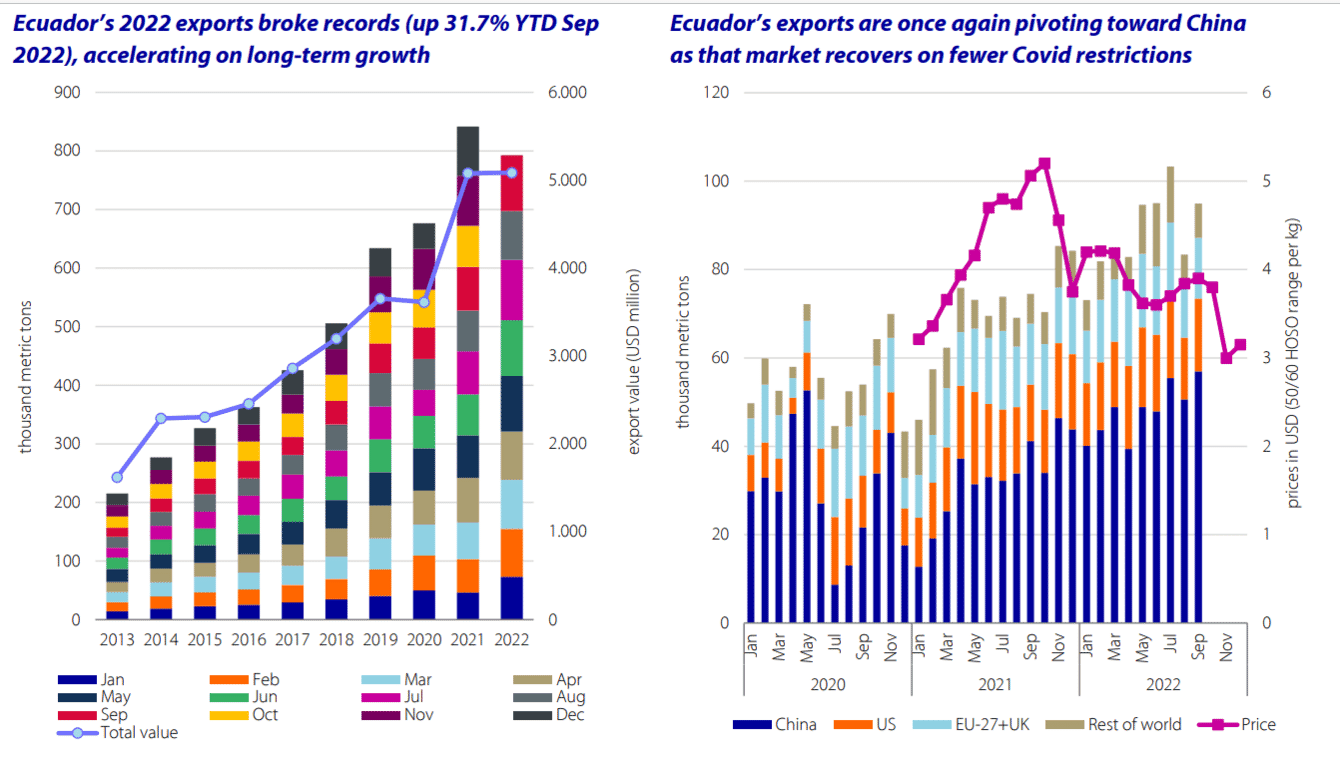

“The price was high at the bottom of the Covid cycle, but since then most of the industry has gone from being profitable to making a loss on a per kilo basis. The story is a little different for every producer but even Ecuador, which increased production by over 30 percent during 2022 – they added the volume of Thailand in one year – is becoming less competitive,” he observes.

“The fact that they’re a dollarised economy, means that they are becoming less and less competitive as the strength of the dollar increases. Secondly they have lost their diesel subsidy, so the cost of production has increased. Many of the small players are no longer profitable, so it’s possible that the large players, who are very efficient and use electric power, not diesel, for their paddlewheels, will buy up the small players and accelerate consolidation,” he adds.

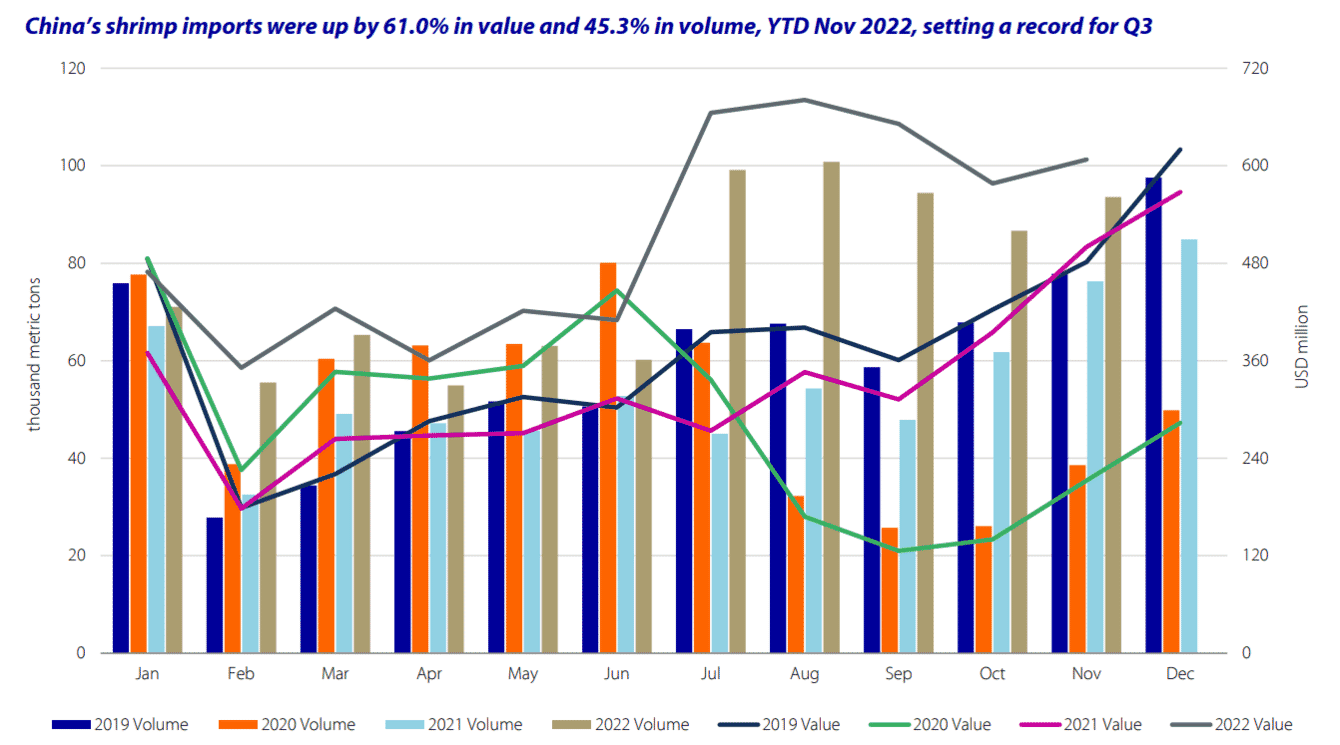

In terms of demand, Nikolik notes that while it began to decline in the summer in the US and Europe, the Chinese market rebounded strongly in the autumn.

The profitability of smaller shrimp farms is under threat, making consolidation more likely © Kurt Servin

“In quarter three they bought a billion dollars of shrimp, compared to the usual figure of $300 to $400 million per quarter – 43 percent more than in 2021. It has to do with the Chinese expectation that the domestic market will open up in a big way – around the end of the year the Chinese government announced more than 20 relaxations of Covid measures and all the importers and traders were getting ready, waiting for people to start going to food service and festivals again. They were expecting the economy to revive in a big way,” he reflects.

“The reality is that it hasn’t quite happened as much as expected. People can go to restaurants, but there is so much Covid that they’re afraid to get infected and are worried their vaccines aren’t as effective as they were – it’s almost like we were two years ago,” he adds.

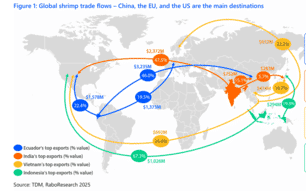

Ecuador was, Nikolik notes, the main beneficiary of the upturn in China and will therefore have the most to lose should China’s shrimp consumption not meet expectations this year. Elsewhere, he predicts that India’s shrimp exports are likely to be 5-10 percent lower in 2022 compared to the previous year – thanks in part to a slowdown in US shrimp consumption and the reduced prices on offer, which tend to lead to a reduction in seeding.

“With prices as they are now, maybe we will see a further slowdown in India. And I also expect a further slowdown from Indonesia – although they were up by about 9 percent in the year to September, I understand there is a slowdown after that, as they are so dependent on the US. That’s where 76 percent of their exports go. And when there’s a slowdown in the US, India and Indonesia are the first to get impacted,” he observes.

Vietnam, meanwhile, were 15 percent up, year-on-year, thanks to the momentum in the market in 2022, but he suspects this uptick will be relatively short-lived.

“At some point the prices will fall below the cost of production and you suddenly need to make decisions about whether you produce less. My predictions for 2023 are that certain producers – mainly in Asia, but also some of the smaller players in Ecuador, will exit the market, as their cost of production is above the price they’re getting for their shrimp. At the same time there will be a demand reaction in 2023 – shrimp is now a relatively cheap protein, so people might start putting more shrimp on the shelves and on the menu. That might reverse what was happening and those inventories that were built up in the last part of 2022, when more supply was offered to the market than was being consumed and caused the price to go down, and some point there will be an inflection – driven by lower supplies and higher demand caused by the low price,” Nikolik explains.

In one year, the country's production grew by 31 percent - more than Thailand's entire annual shrimp harvest © Rabobank

“I don’t know whether that will be in H1 or H2. It depends on whether China can maintain the big demand they had in Q3 and Q4 – if they don’t then the prices will remain low for longer and it will take longer for an inflection point to come,” he adds.

And, the longer the inflection point is delayed, the harder it will be for the farmers.

“I think it’s a very tough period for the shrimp farmers, unlike the salmon farmers. Although salmon farmers might face a big tax increase, they are still profitable, whereas the shrimp farmers are not being profitable on a per kg basis and they are small players who have a harder time to deal with making a loss,” he observes.

According to Nikolik, most shrimp players started to lose money in Q4, but it will be another 100 days or so before the next harvests are due, so it’s too early to tell if there will be a corresponding drop in supply – or in price.

“It’s even harder to understand how long it will take for retail prices to change – it takes 2-4 months before retailers take the price down, or food service changes menus,” he concludes.