Since 2022 China has dropped out of the top 10 of the world’s top net exporters of seafood © Shutterstock

So notes Gorjan Nikolik, Rabobank’s senior seafood analyst, in discussion with The Fish Site about the bank’s latest report on global seafood trade dynamics.

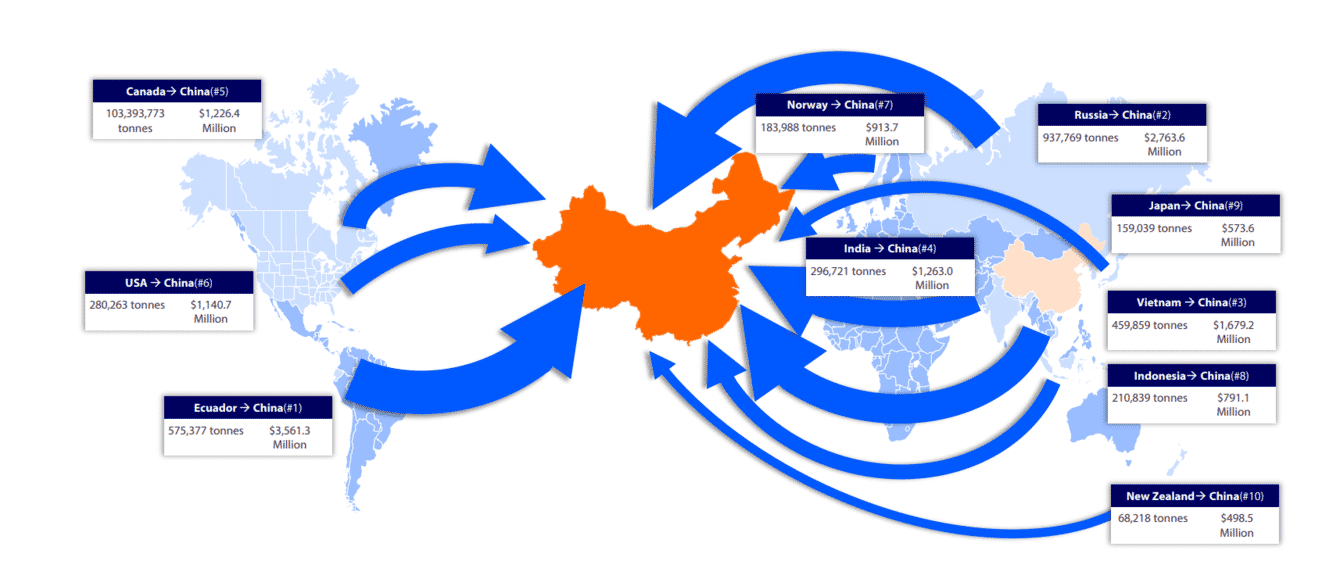

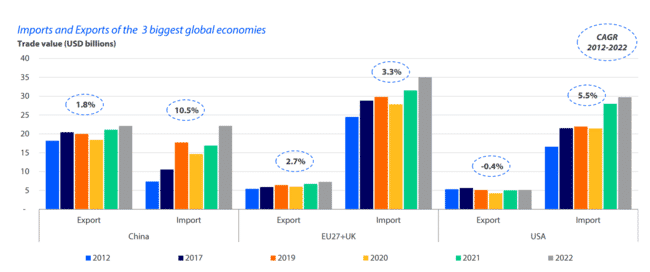

As Nikolik points out, China was consistently the world’s top exporter of seafood (in value terms) until 2017, when it was replaced by Norway. Meanwhile, since 2022 it dropped completely out of the top 10 – compounding a trend that has been accelerated by macro-economic forces since Covid, during which time China has experienced meteoric growth in the exports of more valuable goods.

“Even in 2017 China’s net seafood exports were worth $10 billion – which is astonishing for a country that has such high seafood consumption. But then, by 2022, they weren’t even in the 10 net exporter list. Something happened in the Covid period and what I believe happened is that the Chinese government gave up on being a net exporter and identified different priorities, in line with the country’s declining population,” he explains.

And the switch in priorities appears to be paying off in several, hugely lucrative fields.

Many of these come from countries that have comparatively small populations and access to excellent natural capital © Rabobank

“Pre-Covid China’s car exports were 10 times lower than those from Germany or Japan. But, following Covid, China’s huge investments in making electric cars – a field in which they control the whole value chain – paid off and they’re now the world’s number exporter of electric cars. You can see that China’s economy is gradually shifting towards higher value activities, including pharmaceuticals as well as cars,” he reflects.

History repeating?

According to Nikolik, it’s a natural progression. After all, while the US and EU both have good resources for seafood production – in terms of coastline and fresh water – they are not being effectively utilised, due to the wealth of other employment options available.

“People feel that they can do better jobs – more people want to work in semi-conductors than in seafood. Most mature economies would prefer to import seafood, not grow it themselves. In Europe and the US seafood exports are limited, production is limited – Europeans import $35 billion worth of seafood, and Americans import $30 billion and our imports are growing a 3.5 percent a year,” he observes.

“Even China has a finite number of people – in fact they have a shrinking working population – so we can expect this trend to continue, as fewer people will be willing – or available – to work in seafood production. Their production will flatten out, they will consume more and import more. Until recently, when they were a net exporter, they were contributing to global seafood supply, but now they will be more and more like Europe or the US. Chinese imports are growing at 10 percent and their exports are growing at 2 percent – clearly this trend is going to continue. It might take decades, but in time China’s seafood graph will look similar to those of Europe and the US,” he adds.

Nikolik suggests that this is only going to increase thanks to their success in exporting higher value products, such as electric cars © Rabobank

A marked contrast in demand between China and the West

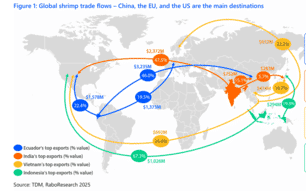

At a time when global demand for many key seafood commodities, especially shrimp, has been decreasing – and prices have declined correspondingly – changes in China’s seafood trade patterns offer hope for beleaguered seafood export-focused economies.

This is especially the case given the decreasing demand for many of the key seafood species – other than salmon, which continues to thrive in the US market in particular – in the West. Indeed, as the report shows, US seafood imports values fell by a massive 22.7 percent in the first half of this year, while in Europe they dropped by a comparatively meagre, but not insignificant, 3.2 percent.

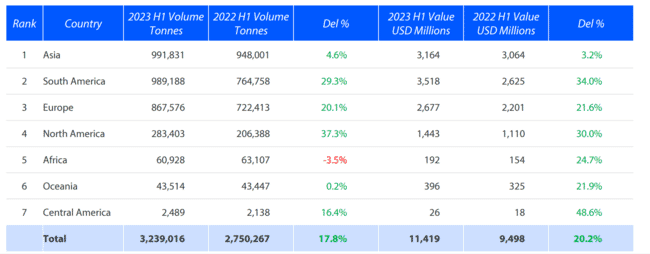

China’s demand has been in marked contrast, with growth akin to – but more extreme than – that experienced in the US, during and immediately after, Covid.

“China has been a demand driver in the last few years, especially the last two years when its seafood imports have increased by 17.8 percent and 20.2 percent respectively. Changes in China are good for net demand at a time when there’s less demand from the US and Europe. The US is likely to have depressed seafood demand for another year, while the European economy is weak and disposable incomes are low, so the slump in demand there could last for over a year,” Nikolik forecasts.

“And if the conflict in the Middle East escalates, fuel costs will increase again, just as we are coming out of an energy crisis. And another energy crisis, combined with high interest rates, will make for a really difficult 2024 and 2025. It’s not an easy time to sell seafood to Europe and the US,” he adds.

Nikolik expects this to continue, even if it slows slightly during 2024 © Rabobank

Key beneficiaries to China’s reduced exports include a number of Latin American nations. As Nikolik notes, in 2022, Ecuador and Chile were joined by Peru and Argentina in the list of the top 10 exporters.

“It’s normal that when a country with a high endowment of people starts to focus on other sectors, that countries with high levels of natural resources on a per capita basis, will take over. Peru sells 80 percent of its fishmeal to China and Argentina has a high dependence on China, for its shrimp and a few other species,” he points out.

However, it will be interesting to see what impact the reduction in Chinese seafood exports will have on those countries, including much of sub-Saharan Africa, that have been reliant on imports of cheap Chinese tilapia.

While it could cause food security concerns, it could also help to catalyse the necessary growth of Africa’s fledgling aquaculture sector – a sector that has struggled to fulfil its potential and a sector whose growth will be essential to provide the nutrition needed for the continent’s rapidly growing population.