© Tor McIntosh

Apart from two large yellow buoys bobbing in the water there is little to indicate that we are passing the site of a licensed seaweed farm. But despite the lack of obvious ‘seaweed farming’ paraphernalia, the occasion is momentous – my boat companion Jennifer O’Brien is getting the first look at her company’s inaugural seaweed farm in Cleggan Bay, in the north-west of Connemara on Ireland’s west coast.

Skippering the boat is local fisherman Johnny King, owner of the 10-hectare site located a short boat trip from Cleggan Pier, who is leasing the licensed seaweed farm to O’Brien. Farming native seaweed in Ireland’s waters for use in Sea & Believe’s macroalgae-based alternative seafood products – as a core ingredient but also as a functional ingredient for use as a binder and flavour – was a business goal she mentioned when she spoke to The Fish Site last year. Having the opportunity to lease King’s site to cultivate Palmaria palmata – a native red seaweed, also known as dulse – without enduring the potentially long wait to secure her own licence, has fast-tracked her seaweed farming ambitions.

“For the moment this is a great opportunity to showcase Palmaria and show the work we're doing to investors – it's essentially a proof-of-concept site,” explains O’Brien, who hopes the success of the pilot site will allow Sea & Believe to establish several farms along the west coast of Ireland, growing a range of native seaweeds. By developing a network of small-scale farms O’Brien envisages her company playing a role in improving livelihoods and increasing job opportunities for coastal communities, while helping to restore the area’s marine ecosystem – and potentially boost local fish stocks such as mackerel that, as King attests, have depleted in recent years.

P. palmata has an unusual reproductive cycle that makes it challenging to cultivate successfully – a challenge a team of seaweed scientists at the Carna Research Station in the west of Ireland have cracked © Susan Whelan / Irish Seaweed Consultancy Ltd

From wild harvest to farm site

With its excellent nutritional value – including high levels of protein and a wide range of essential amino acids, B6 and B12 – and appealing taste, choosing to cultivate P. palmata as a food-grade seaweed was a simple decision. However, it’s a species that hasn’t been commercially farmed due to its unusual reproductive cycle, making it a challenging seaweed to cultivate successfully, despite various attempts.

Having previously used wild harvested P. palmata in her plant-based seafood products, O’Brien was aware that in order to scale her business she would need large quantities of the species, meaning she could no longer solely rely on wild harvest. Troubleshooting this dilemma she reached out to a team of seaweed scientists, including Dr Maeve Edwards who has an extensive background in pioneering algal research and has worked with Michael O’Neill on his seaweed hatchery venture on the Beara peninsula in West Cork.

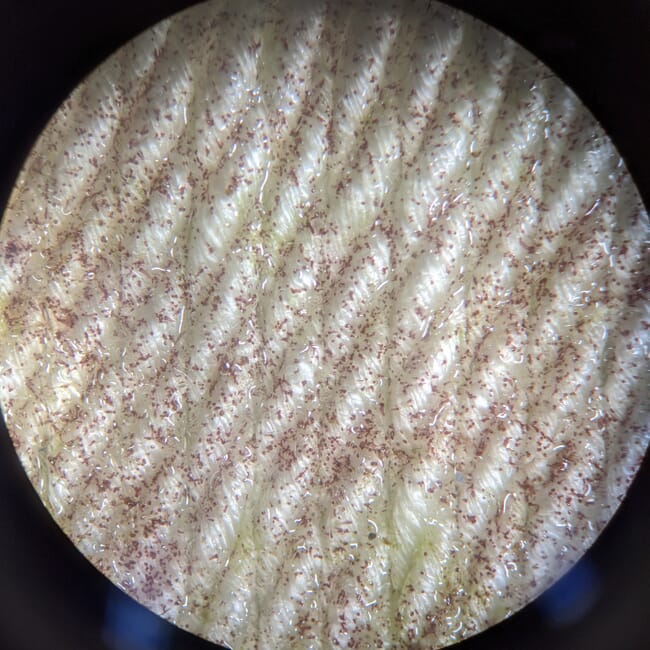

More recently Edwards has been co-supervising research undertaken by University of Galway master’s student Susan Whelan. Based at the Carna Research Station (CRS) – an aquaculture research centre of the University of Galway’s Ryan Institute located in a Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking) region in south-west Connemara – Whelan has been trialling a unique and revolutionary way to successfully culture P. palmata using wild-gathered tetraspores (asexual spores produced by red algae).

© Tor McIntosh

Over the past year Whelan has gathered a staggering 6,000 samples of P. palmata from sites along Ireland’s west coast – where it thrives in the wild along the exposed Atlantic-facing coastline – bringing the samples back to the lab to study the seasonal changes in the reproductive cycle. “I'd look at them to see if they were males or tetrasporophytes, then look at the frond to estimate how many spores had been released to find out when the best time was to collect them to gather their spores,” she explains.

According to Edwards, Whelan’s research has provided a clear understanding of the species’ lifecycle. “In the past we would have cultivation issues, they would either work or wouldn't work, but Susan's work has really stabilised a lot of that early boom or bust research. Through intensive work like Susan's we are confident enough now to say it does have a commercial future, which is not just confined to research.”

A scientist’s perspective

Edwards’ involvement in O’Brien’s plans to farm P. palmata to meet the biomass demand required to scale-up her business has certainly elevated the project. “The problem with scale-up is the challenges are so many that you have to continually monitor and improve and tweak every year. So you still get your biomass, but it's a great advantage to have scientists on board to understand the metrics,” Edwards says, laughing at her ability to blow her own trumpet.

Learning about the history of the CRS from Edwards – which was established in the 1950s initially as a field station and later as a facility for basic and applied research of many native and novel aquaculture species, from mussels and salmon to cod and purple sea urchins – it’s clear that aquaculture has played a key role in the area for decades. But, as Edwards reveals, slowly over time a lot of the independent fish farms have ceased operations. “It's a risky industry and people just couldn't handle the risk – they couldn't handle the losses,” she muses.

Whelan has been trialling a unique and revolutionary way to successfully culture P. palmata by growing wild-gathered tetraspores (asexual spores produced by red algae) on twine in the hatchery at the Carna Research Station © Susan Whelan / Irish Seaweed Consultancy Ltd

As someone who is naturally risk-averse – a trait she puts down to being a scientist – Edwards is particularly interested in exploring ways to de-risk the emerging seaweed industry in Ireland. “It's good for everybody: it's good for investors, it's good for incomes for farmers, and it just makes everybody's life a little bit easier,” she explains.

“The volatility of the sea is something that we always have to work with, not work against. In particular with the climate crisis we can only expect conditions to get more challenging, so we have to be forward thinking,” reveals Edwards. “But if we prove that we are de-risking our activities, then it will make it easier to have conversations with the investors that are needed.”

Scaling an emerging industry

Ireland’s long coastline and cool waters present ideal conditions for cultivating seaweed, but the industry is still in its infancy. However, Bord Iascaigh Mhara (BIM) – Ireland’s state agency responsible for developing the Irish seafood industry – recently published a strategy to increase the volume of farmed seaweed in Ireland, which, among other factors, identifies that only having one hatchery facility – established on a research and development basis rather than a commercial one – is hampering the scalability of the industry.

Both Edwards and O’Brien echo the concerns about the lack of commercial hatcheries in the country for the cultivated seaweed sector, with Edwards identifying hatchery space as a key challenge when looking to scale production commercially. As she points out, “what is put out on the lines at sea to on-grow is dependent on what can be grown in the hatchery space.”

Spawning strong seedlings in the hatchery environment is vital to ensure they are tough enough to withstand the short growing season at sea © Susan Whelan / Irish Seaweed Consultancy Ltd

Currently limited by the amount of seedlings that can be grown from the small hatchery space at the CRS, both scientist and entrepreneur are realistic about the quantity of biomass that could be harvested in the first year at the pilot site in Cleggan Bay, with Edwards reluctantly stating “you should be getting hundreds of kilos and then you're increasing from there, but it depends – I hate predicting the future!”

Her reticence is understandable when there are uncontrollable factors that could impact the numbers, often occurring when the lengths of seeded twine – initiated and maintained in the hatchery – are put out to sea. This means Edwards’ focus is on the control that’s possible in the hatchery environment to spawn strong seedlings that are tough enough to withstand the short growing season at sea, usually from November to May.

“From my perspective it's a lot of control in the hatchery, but it's not far off from being cracked and it just needs to be standardised and repeated,” explains Edwards. “I think seaweed [aquaculture] has to be made more efficient, because whatever way we do it in Europe, it's expensive – our labour rates are high and our sea conditions, while they're good for the seaweed growth, can be challenging to work in.”

The taste of Connemara

The sheltered bays along Connemara’s coastline provide the perfect conditions for growing P. palmata. As Edwards acknowledges: “There's an advantage to not having heavy industry on this side of the island, meaning the population is very low, the water exchange is high, and there's lots of interesting bays to work in – you have enough water turnover, enough nutrients, but you also have enough shelter.”

But there’s more than just ideal conditions that make this remote and rugged coastline in County Galway a sweet spot for P. palmata – and that’s all to do with taste. O’Brien – accompanied by agreeable nods from Whelan – points to the ocean nutrients, the swell and the currents in the area, meaning Connemara is “producing the tastiest, in my opinion, seaweeds that are out there,” she enthuses.

Now that this project is making headway, O’Brien’s excitement is palpable as she observes the dormant farm site from the boat and chats to King about purchasing equipment and setting up the infrastructure ready for outplanting the hatchery-grown seedlings in December. But, as easy as it could be for her to get caught up with only focusing on the emerging seaweed farming side of her business, she knows it’s important to keep pushing ahead with developing her macroalgae-based seafood products.

“We're selling products with seaweed, but this [commercially farming seaweed in Ireland] is the future – this is where we see things going,” she explains. “It's a very new industry, it's still emerging and it's probably going to take 10 years for the industry to commercialise and to stabilise. So our next stage is to do a big sale with our products, get some revenue, and ideally spawn the seedlings in early autumn and have them ready to go out to the site at the end of the year for our first harvest next year.”

The collaboration between O’Brien and Edwards oozes potential, and the duo are not fazed by the scale-up challenges. They are clearly passionate and driven to kickstart the commercial seaweed farming industry in Ireland with P. palmata. Despite her bias towards Palmaria, having spent much of her career researching the species, Edwards knows the native palm-shaped red seaweed is a high value species so “is worth that little bit of extra work to get it there [successfully cultivated] because if we can, we can make Ireland a real stronghold for it.”