© Aaron McNevin, WWF

When my parents were planning for retirement, they looked for a peaceful place that was still in the metropolitan area but far enough out to escape the hustle and expense of the city. They found an idyllic plot of land with mountains in the background and a stream running through the property but quickly abandoned it when they learned that a pig farm would be constructed a short distance away. They enjoyed their bacon but didn’t want to live near the pigs. And they chose accordingly.

My parents are not alone. It’s not unusual for people to oppose certain developments in their local community – such as a landfill site or a solar farm – that they might otherwise be fine with as long as it was located further away. While my parents did not purchase that home near the pig farm, someone did. The impacts that came from that pig farm were experienced by another.

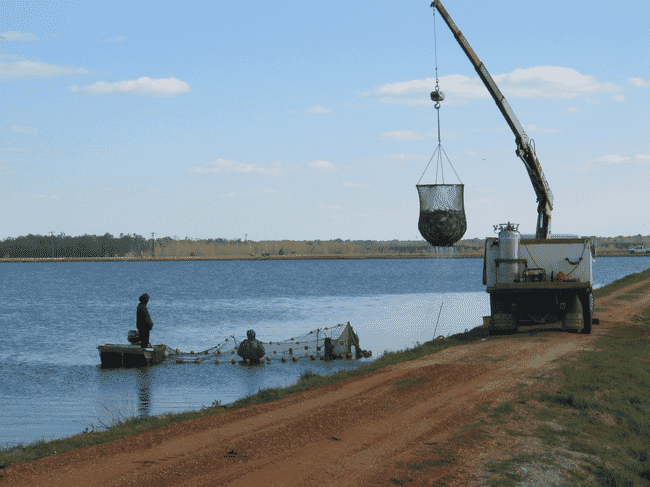

I’ve recently been thinking about US consumers’ reticence to allow production in their local communities – specifically as it pertains to aquaculture, which is my own area of work. Today, the relatively low aquaculture production in the US versus other countries in the world contributes to an enormous US seafood trade deficit, with 70-85 percent of seafood consumed in the US coming from other countries. That consumption has impacts on the planet and people. And an impact is an impact, independent of the country where it is felt.

Most US consumers are unaware of those impacts. They are too busy just trying to make ends meet to inquire where their seafood comes from. They can’t afford to dive deep into the origins and practices used to produce aquaculture products. Also, there is an inherent trust that retail, club stores and restaurants source their food from reputable actors. This sense of security allows for consumers to shop based on prices, even considering that most aquaculture products can’t be traced back to farm origin and the US government only tests about 1 percent of its seafood imports.

Both sceptics and supporters of aquaculture have been closely following some of the recent developments in the US sector, including increased seaweed and shellfish farming, CP Food’s big investment in US shrimp production and identification of offshore aquaculture sites where farmers are poised to begin operations. With the US aquaculture sector set for a resurgence, there are opponents who point to the potential negative environmental impacts of aquaculture – from pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, wild fish dependency, habitat conversion and chemical use.

© CP Foods

These are real impacts. But here’s the thing: compared to many areas of the world where most of our aquaculture currently comes from, wealthier countries such as the US have the resources to avoid and mitigate many of these detrimental impacts. In doing so, we could simultaneously create new jobs that strengthen local economies, help reduce some of the environmental burdens on less affluent nations and make progress toward many of our global environmental goals – which, incidentally, all people everywhere have a vested interest in achieving.

And when it comes to easing the burden of less affluent nations, it’s important to point out that producers in many other parts of the world are trying to ensure aquaculture development is done right. Stricter controls are being put in place for aquaculture in national parks, farm permits are being eliminated in some public water bodies, commitments to protect habitats are being set, and greater community consultation is taking place prior to aquaculture operations being sited.

But there are still barriers, as poverty and the growing wealth gap make it harder to address broader environmental degradation caused by aquaculture. Poverty doesn’t allow for long-term planning and enforcement of policies to protect natural resources. Poverty fuels desperation, and in desperate times the next piece of food is more important than the promise of food in perpetuity.

So how can we expect poorer nations to prioritise the appropriate siting of farms, limitations on waste discharge, importation and production of exotic species and natural habitat protection? And while there needs to be wealth concentration for investment, we’re now at the point where the inequity of supply chain value-sharing has become so extreme that pets in developed countries are nourished better than the farmers who are feeding us.

It’s not just unethical, it’s self-defeating. People and companies are taking advantage of poverty, and without poverty alleviation we won’t get environmental conservation.

The US has poverty too – not nearly as extreme or pervasive as other countries – but still, our own enormous wealth gap forces people to shop by price, and as a result there is a large market for food at the lowest cost, regardless of the consequences. We need to value our food more than we do, in terms of both nutritional value and the impacts it has on our environment and our global citizens.

Abalone are among the most prized shellfish species in the world © Aaron McNevin, WWF

A resurgence in US aquaculture could set a better example, one that shares value throughout the supply chain, so people can earn a living and workers can have a savings account. The US aquaculture sector could expand the US Shellfish Sanitation Program, or something akin to it, so there would be real traceability. There could be greater pride in the product produced – feed should be viewed not as a bag of pellets to make fish grow, but rather as nutritious ingredients sourced to ensure environmental sustainability, not work against it.

Aquaculture producers could work towards a more optimised system, where the intensity of production is matched with the quality of the product, rather than at the expense of it. It could be the return of the family farm, situated near urban centres with “plug and play” technology that helps make its operation easier and less impactful – solar energy, new water treatments to foster re-use, precision feeding, or the recycling of algae or organic sediments for greater circularity in the food system.

But to get there we need to accept that volume purchasing isn’t sustainable; it doesn’t allow for an embedded value to be conveyed for food. And volume purchasing will promote or sustain poverty for workers in aquaculture supply chains – both in the US and abroad.