Frantzen has worked on various fish farms and is getting experience in business management and the startup sector

Despite only being 21 years old and having a full-time aquaculture management degree, he is working as a business developer at Olaisen Blue, having previously worked as a salmon farmer for Ellingsen Seafood and Lofotyngel, and taken up internships with SalMar and Nordlaks. He was also part of the Insight Academy started by Aino Olaisen, one of the owners and chairwoman of Nova Sea.

Can you tell us a bit about your background?

I’m from the Lofoten Islands. Growing up on the coast inspired me to pursue a career that had something to do with the ocean. I remember telling my dad that I did not understand why I had to go to normal school, thinking they should just place me on a fishing boat. As I grew up, my fascination with the sea evolved, and my interest in other subjects – like biology, chemistry, law and economics – also grew. I wanted to have a broader understanding of the world, and to work with many different people.

Why did you decide to pursue a career in aquaculture?

When I completed high school, the choice of what university subject to choose stood between three things: shipping, maritime logistics and aquaculture. The reason why I ultimately chose aquaculture was the endless potential within it. I saw an opportunity to join a young industry that was modern and forward looking. Aquaculture will change huge amounts in the coming decades. I wanted to be a part of that.

How have you managed to fit in so many work placements during your time as an undergrad?

Frantzen is capitalising on an opportunity from Olaisen Blue and is working as a business developer

By taking every opportunity that I had, by showing active interest in what I was doing, being invested in what I was doing and knowing why I was doing it. I have always been sure to give it my all, and more opportunities keep on arriving.

Why don’t more graduates get involved in farming?

I think there is a growing gap between farming and office jobs, which I find alarming. As the industry has grown, competence in specialised positions is now required. However, those who built this industry had practically no education but were incredibly stubborn people who were not afraid to do the dirty work, as well as running a business. The industry should always keep this in mind, and remember what aquaculture really is.

What have the highlights been?

One thing that stands out is having had the opportunity to meet so many amazing people along the way. There is so much knowledge to be gained by being with people in the industry. The best knowledge is not taught at university, it is out there.

What have you learned from the farming experience and where is there the most scope for Norway’s salmon sector to improve?

I believe there are several elements where Norway´s salmon sector can improve. Firstly, overall fish health needs to be addressed, as well as work to improve the public perception of the sector.

There are three key areas where we are not as good as we think we are and have not improved in the last 20 years:

Frantzen believes that Norway's salmon sector can improve across multiple areas to earn greater public acceptance

- Production time at sea: This should ideally be kept much lower than it is today. The less time the fish spend at open sea pens, risk goes down. Both in terms of sea lice, but also other pathogens that are freely in the marine environment. If we can start to bring this down to further, either by evolving the salmon further with breeding or finding alternate production methods, I think we would see a strong correlation with mortality at sea will go down.

- Mortality at sea: in the latest report from the Norwegian Ocean Institute the mortality on a national basis is around 15 percent, but varies throughout the country’s different production regions. I think we should of course aim to have this as low as possible, but I think we should reach 5 percent. This is important from an economic standpoint, but even more important from an ethical position. We should always look to improve this.

- eFCR: the rapid increase in raw material prices demonstrates that we need to find alternative protein sources, that are also closer to where we actually produce the salmon. Not only from an economic perspective, but also from an ethical (climate change) standpoint, given that we import so much of our raw materials.

On the feed side of things, there is an absolute need to find alternative ingredients, and we need to tackle the industry’s CO2 footprint from its core (which is feed) instead of focusing too much time on cosmetic improvements like building new electric boats.

What are your thoughts on closed-containment, RAS and offshore production?

All the three certainly have their benefits, and I think they will each play a role, but it is worth noting the benefits of the existing open net pen system: it is cheap, reliable and – when done right – easy and sustainable.

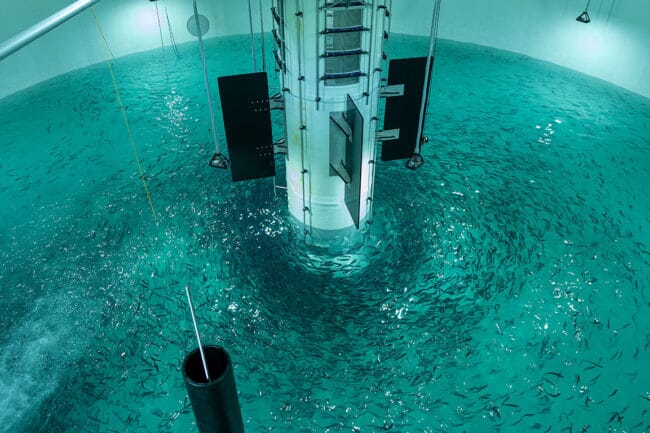

Frantzen hopes that innovations like RAS will help the industry reduce the duration of the sea stage, helping reduce disease burdens © Salmon Evolution

Starting off with RAS for producing bigger smolts, then moving them to either closed-containment or offshore production is something I really believe in as an efficient way of doing things. But I don’t think we can throw away open pen system just yet.

You’ve worked with cod – do you think Norway should look to diversify its aquaculture industry more?

Absolutely. I think we can grow the whole aquaculture industry. A key success factor that made the salmon industry grow, was sharing knowledge and cooperation. I think we see the same happening in the cod sector, where a shared success will benefit everyone.

Cod farming itself shows great potential, and I believe it would be beneficial for the seafood business here in Norway, as well as in general, to supplement the seasonal supply from wild fisheries.

Other marine species, like halibut and wolf fish, also show potential. I also think we should pay more attention to the production of micro- and macro-algae.

The meeting took place at Havets Døgn's annual event © Image credit

How have your friends and colleagues reacted to the resource rent tax proposals?

Initially with shock and disgust. While many of us agree that we should indeed pay more tax, the haste to introduce a taxation system that was not well planned, that showed little understanding of the industry and – overall – a lack of interest to understand the industry, was embarrassing.

Now that it has calmed down, it feels good that we can start to focus elsewhere, not just on the tax. I think the government and the industry can reach an agreement – perhaps somewhere between 10 and 20 percent – that will benefit both parties.

What’s your current role with Olaisen Blue and do you see a good pipeline of innovation emerging?

I have been a part of the Olaisen Blue team since August, I have helped to host the Lovund Days event, as well as helped to select three new startups to join our accelerator programme. Now that we have selected our three startups. Last year I worked closely with BioFeyn and I am looking forward to building a relationship with the new startups and helping them further. We will also be hosting a demo day and Lovund Days this year again.

Regarding a good pipeline of innovation, I believe that the new taxation could be beneficial. Now, the need to maximise profits and improve what and how we do things is a lot more important. Tools such as AI can benefit the industry. There are definitely exciting times ahead.

What do you plan to do when you graduate?

It may sound like a cliché, but my plan is to continue what I have done, to be prepared for whatever opportunities arise, and take good care of the opportunities I already have.

What would you like to be doing in 10 years’ time?

I would love to be looking around me and feeling that I am part of the evolution of the industry. I don’t know exactly what or where that would be, but that’s my overall goal.