The report, written by the bank’s chief seafood analyst Gorjan Nikolik, is largely positive about the prospects of the global salmon sector – with demand for the fish growing despite the recession. However, Nikolik admits that he is deeply concerned by the potential impact of the new 40 percent tax.

“While Rabobank can only speculate on the outcome, a significant additional tax is likely to be imposed on salmon farmers. This could have both short- and long-term negative effects on growth and innovation in the industry,” states Nikolik.

“We lend to the large salmon players globally, including those in Norway, and it is a moment for us as a bank and others who are stakeholders to the sector to mention something in the public domain – they could reverse the growth of the sector,” he adds.

“There are several issues with the tax. First of all the way it was introduced suddenly, without consultation with the sector – which creates a risk premium for investors in the industry. Even if the tax is not as high as the 40 percent originally announced by the government – I assume it will be somewhere between 20 and 35 percent – suddenly Norway will have the most taxed salmon industry. The government is assuming that Norway will continue to farm salmon as it’s not possible for such a big industry to move in the short term. But, theoretically speaking, salmon farming – unlike hydroelectricity or mining – can move,” he explains.

“Either way the growth rate will become lower. There will be fewer new jobs and less growth so, over time, they might lose the advantages of higher tax. And, in a sector like salmon, in which you need to invest a lot just to remain competitive and sustainable – it’s possible that a loss of market share will start to become a loss of competitiveness, at which point it will become more profitable for Norwegian large corporate farmers to exit coastal salmon farming or start to invest in either offshore or full land-based production,” Nikolik warns.

“I think they’re really risking one of their best industries – they’re the drivers of innovation, they’re the drivers of profitability, their companies bring profits into Norway. But, after a while, you can imagine Norwegian companies investing in full RAS production in Europe or the United States, or offshore installations that are not in Norwegian waters,” he adds.

Nikolik believes that the new resource rent tax will spur Norway's salmon farmers to reduce their investments and dramatically change their farming practices

Most Norwegian salmon farmers will, Nikolik predicts, initially reduce their investments in the sector. However, he adds, they might decide to radically change their farming systems in the long run.

“If you move your production from the coast to land-based post-smolt farms you not only get bigger smolts and bigger licence allocations but you also pay a lot less tax. And the same goes for offshore – if it is defined as a different licence, which we will know in July – the speculation is that these will not be taxed, which will mean it makes more sense to grow-out the fish in offshore farms. What makes more sense is to grow smolts up to perhaps 700 g in land-based systems, skip the coast and grow them offshore for with a much lower tax,” Nikolik explains.

“And, what’s more, they might decide to do that in other countries – as offshore is much more moveable. It really motivates the industry to move way from the Norwegian coast, which means in the long run the tax will have failed and the government will earn a lot less, “ he argues.

“Initially the government might raise the 4 billion NOK that they are aiming for, but after a while the industry will adjust – if the conditions are not right than the growth could reverse,” he adds.

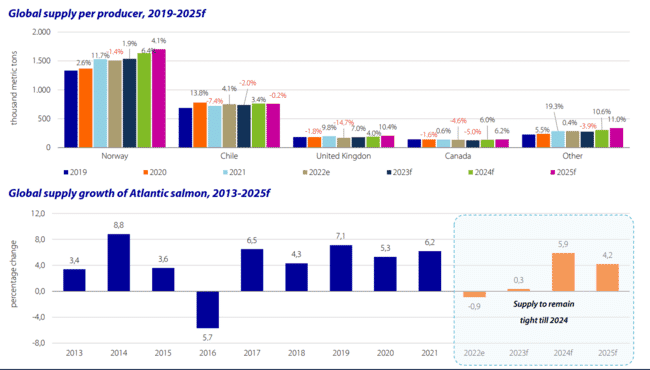

The bank expects supply to remain tight until 2024 © Rabobank

Low growth

Regardless of the tax situation, the report suggests that global salmon production is unlikely to grow by more than 2 percent – with Chile experiencing setbacks caused by widespread outbreaks of salmonid rickettsial septicaemia (SRS) and recent government regulations which limit growth of individual sites to no more than 3 percent a year, a rule that didn’t previously apply to Region XII. Meanwhile Norwegian production is likely to be limited by colder water temperatures and the large harvests at the end of 2022, as producers sought to harvest more fish before the new tax system was enacted.

“The number of fish is higher in Norway, but the biomass is lower than in 2021 or 2020 – either because they harvested the large fish before the tax or the growth rates were slower than expected,” Nikolik observes.

“The good news is that growth should normalise later in the year. Usually after a few years of low growth you typically get high growth – partly due to prices, partly due to unutilised things becoming utilised. It is possible Norway will grow by 6 percent next year, but that will depend on the biological performance,” he adds.

Strong demand

According to Nikolik, any increase in production is likely to be met positively in the market.

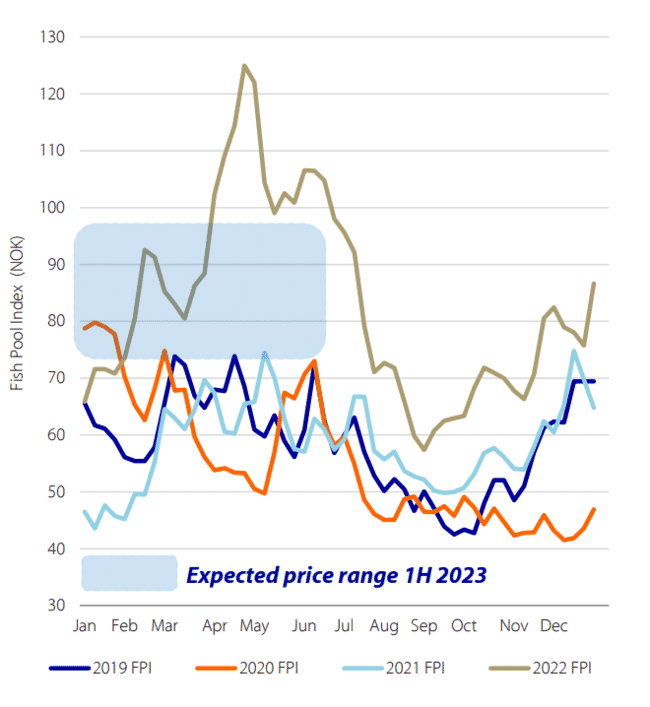

80 NOK / kg is, according to Nikolik, "the new normal"

“Everything we see so far points to salmon being a very resilient species – almost all seafood species in the US retail market have come down in volume and in value but consumption of salmon is remaining high. And food service demand hasn’t come down in either Europe or the United States. We talk about recession but you don’t really see that in food service yet, while in retail it seems to be mainly the most expensive species that have seen a drop in demand. For salmon were going into this year with record demand combined with a weak supply, so we expect high prices – ranging from 75 to 95 NOK per kilo. 80 NOK is the new normal,” Nikolik explains.

Meanwhile, in terms of cost, Nikolik notes that although feed prices are stabilising, or even falling, the cost of production will actually be higher this year than during 2022.

“Salmon harvested in 2022 consumed comparatively lower cost feed in 2021, while the salmon harvested in 2023 will have eaten expensive feed throughout 2022, so overall the cost of production will stay high until the end of the year,” he explains.