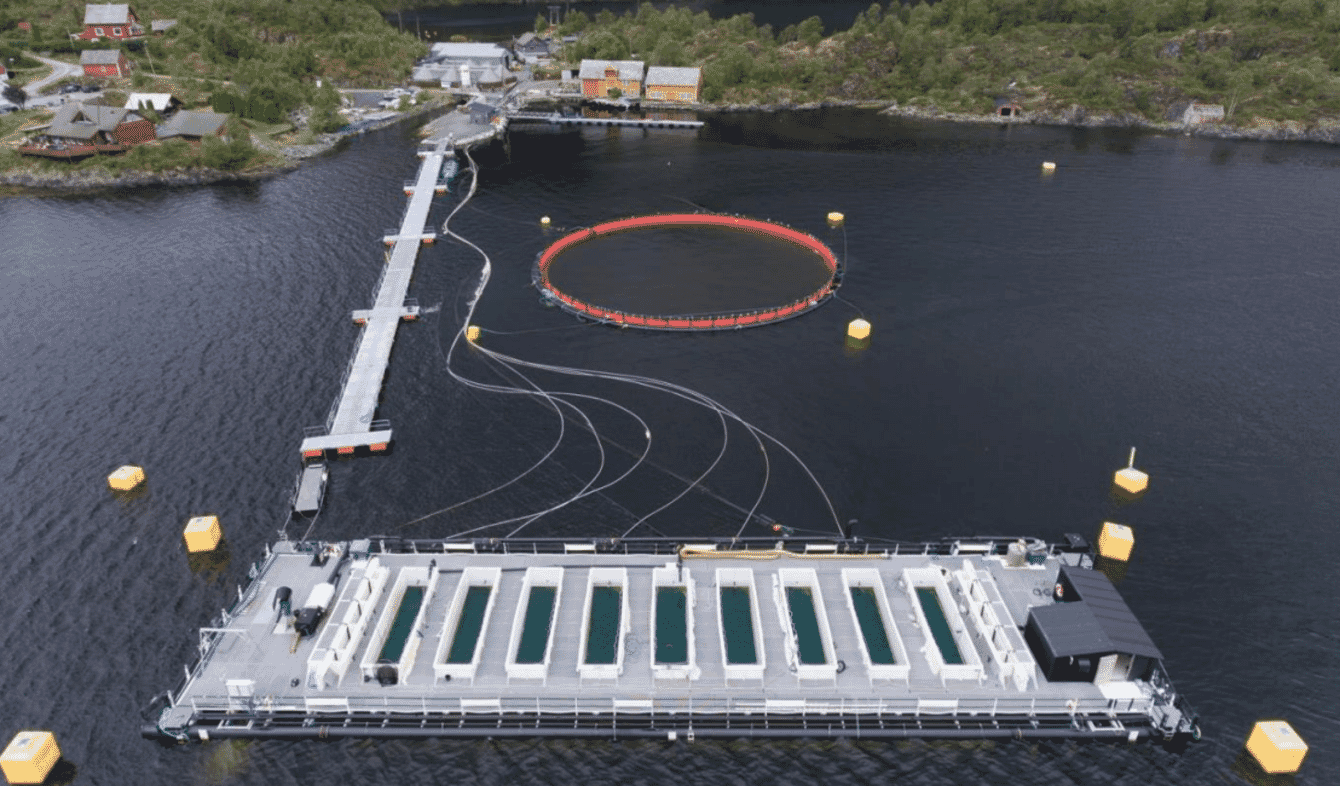

Semi-closed containments systems may help address some of the husbandry and sustainability challenges in salmon aquaculture © Preline

In a recent benchmark study published in Aquaculture Research, researchers road tested the Preline raceway platform – a semi-closed containment system – to see if the systems could address husbandry and sustainability challenges during the sea stage of salmon farming. The team tracked the growth and survival of six cohorts of salmon in the system – from when they reached the post-smolt stage and through the grow-out phase. They compared this performance it to post-smolts that were raised in a conventional rearing system.

Initial trial results showed that post-smolts in the Preline SCCS had a significantly lower sea lice counts, higher growth rates and final weights than post-smolts in the control cohort. Salmon in the SCCS also had higher survival rates when compared to fish raised in open net pens. This suggests that post-smolts raised in semi-closed containment systems are more resilient – which could yield benefits when the fish enter the final grow-out phase in seawater.

"We think these findings are both exciting and promising, as they show a possible way for the salmon farming industry to solve its key challenges," says Professor Albert K D Imsland, the corresponding researcher from the trial.

Conventional vs semi-contained

Norway’s salmon farmers are under increasing pressure to shorten the time post-smolts (juvenile salmon that weigh up to 1 kg) spend in seawater. Post-smolts face huge environmental and physiological challenges during this phase. In addition to adapting to the saline environment, they are often exposed to pathogens and difficult water conditions.

On the husbandry and biosecurity side of the equation, recurring pain points like sea lice, disease, escapes and potential environmental impacts stem from post-smolts sustained “exposure” period in seawater. Recent industry data found that approximately 20 percent of smolt in conventional sea cages are lost before they reach harvest size. Reducing sea phase duration could address these challenges and improve production volumes.

Semi-closed containment systems separate the fish from the ocean environment by surrounding the farm with a physical barrier © Preline

The industry has embraced two general approaches when tackling these issues: raising juveniles on land until they’re more robust and making fundamental changes to conventional sea cages. For sea cages, new designs create barriers between the fish and surface sea water, limiting their exposure to environmental stressors like sea lice and pathogens. The barrier systems also reduce organic pollution from farm activities.

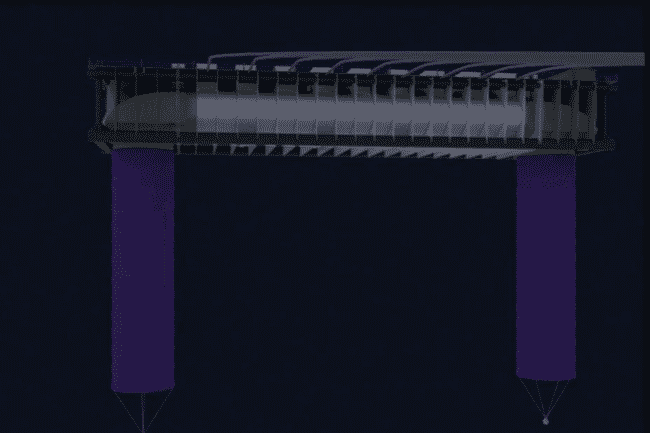

Semi-closed containment systems (SCCS) fall into this cohort – the tech separates the fish from the ocean environment by surrounding the farm with a physical barrier. The system’s water supply comes from the deep sea, where it is usually cleaner and free from juvenile sea lice and harmful plankton. SCCSs are starting to gain traction as they can abate many of the environmental challenges seen during the sea stage. Other trials suggest that opting for semi-closed containment lets operators increase their stocking densities without courting disease challenges or organic pollution.

An additional feature of semi-closed systems is related to water temperature. Since the water intake comes from lower ocean strata, there will be fewer temperature fluctuations during the production cycle. Some evidence suggests that stable water temperatures could have a positive effect on the growth and overall fish welfare – which would be an additional boon if the system is adopted.

The system’s water supply comes from the deep sea, where it is usually cleaner and free from juvenile sea lice and harmful plankton © Preline

The trial – from post-smolt to grow-out

For this trial, the researchers wanted to validate the biological performance (growth, resilience and mortality) of post-smolts in Preline’s Fishfarm system and compare them salmon raised in net pens*. In addition to a side-by-side comparison of the SCCS and control groups, the researchers also tracked the role of water temperature on salmon performance. This included comparing growth and resilience in fish that were stocked during the Autumn and Spring seasons.

After assigning the salmon smolts to control and experimental groups, the researchers organised the groups into six different cohorts. Three of the cohorts were stocked in the Spring (cohorts 1, 3 and 5) and the remaining three were stocked during the Autumn (cohorts 2, 4 and 6). As they were transferred to seawater at the Lerøy Vest AS facilities in Western Norway, the researchers created two distinct experimental phases. The first phase tracked the performance of the post-smolts after they were first introduced to seawater until they reached approximately 800 grams (between 4 and 6 months). The second phase observed the fish during a grow-out phase in seawater until they reached 5,000 g. The researchers then compared their performance against the control cohorts who were raised in open sea cages from the post-smolt stage.

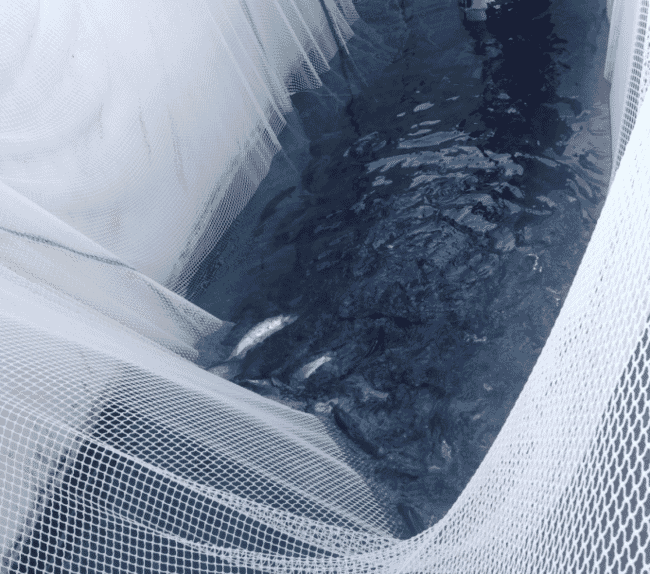

The trial was conducted in two phases, with one tracking the performance of post-smolts until they reached 800 g and the second measuring the grow-out period at sea © Preline

Key results

During phase-1 of the experiment, the researchers noted an improved feed conversion ratio (FCR) and higher weight gain for cohorts in the SCCS. They didn’t observe a significant difference in mortality between the two systems. It appears that seasonal temperature variations played a role in growth performance and FCR, with fish stocked in the Autumn performing better than those stocked in the Spring. Statistical analysis indicated that temperature was the key factor influencing growth in the cohorts at this stage – the rearing system did not play as strong a role.

The seasonal variation was observed during phase-2 of the trial as well. Data analysis indicated that post-smolts stocked in the Preline system in Autumn had an improved feed conversion ratio and lower mortality rate compared to Spring cohorts.

Fish that spent phase-1 in the SCCS showed improved performance across multiple metrics. The researchers suggested that the raceways used in Preline’s Fishfarm system played a role in the production benefits. Raceways are designed to control water velocity – which has a demonstrated impact on growth performance. The SCCS gave operators a chance to expose salmon to sustained swimming and exercise, stimulating their growth and lowering FCRs.

The improved growth performance in the Preline system was also observed during phase-2 of the trial. Post-smolts in these cohorts showed higher weight gain and higher final weights compared to salmon in the control group. This suggests that keeping post-smolts in a SCCS has a positive effect that lasts well into their final grow-out phase in the sea.

When examining sea lice levels, the researchers noted that infestations were significantly lower for post-smolts raised in the Preline system than those in the control cohort – regardless of the season. The team attributed this to the deep-water intake in the SCCS. Since sea lice tend to concentrate in surface layers, taking water from a 30 m depth – below the lice belt – kept infestations low. When examining salmon in phase-2 of the trial, trends in the data suggested that lice infestations would remain lower for salmon that were reared in the Preline system. Field observations also indicated that fish in SCCS cohorts needed fewer lice treatments than fish in control cohorts.

The researchers suggested that the reduced sea lice pressure could be down to the morphology of fish skin. Salmon skin and its associated mucous layer is the first line of defence against environmental stressors and pathogens. Since skin thickness and mucous cell numbers tend to increase in line with growth rates in Atlantic salmon, it is possible that improving growth rates could translate into a more robust skin barrier. Given the myriad of welfare risks and secondary infections that stem from sea lice infestations, ensuring that salmon skin remains healthy and capable of regeneration would be a boon for lice resistance.

The reduced sea lice counts seen in salmon raised in the SCCS could be down to the morphology of fish skin © Scottish Sea Farms

Other factors to note

Though semi-closed containment systems address many of aquaculture’s biosecurity concerns, it’s possible they can play a role in reducing behavioural stresses in fish as well. Salmon raised in sea cages often form hierarchies and can sometimes exhibit aggressive behaviour when feeding – causing stress for the individuals in the cage. Results from this trial suggest that semi-closed raceways could reduce these stressors – the salmon were constantly exercising instead of dominating their neighbours. The improved growth and feed conversion ratio could stem from these environmental changes.

The researchers concluded that using a semi-closed containment system for post-smolts yields numerous production benefits. When compared to conventional salmon farming methods – where post-smolts are exposed to the natural environment in open sea cages – SCCSs can help operators raise more robust fish that reach higher final weights and show greater survivability. The lower sea lice count in semi-closed systems shouldn’t be overlooked either. The system brings production advantages that may help the salmon sector break through its stagnating production volumes.

The full paper can be read in Aquaculture Research.

*Preline’s semi-closed containment system had a rearing volume of 2,000 m³ and was designed to include a 50 m-long raceway platform with an elliptical cross-section. For the sea cages, the researchers used open 160 m conical circular sea cages that had a capacity of up to 200,000 Atlantic salmon each.