Groupers are highly prized throughout Asia and have traditionally been caught using nets, traps and baited hooks, but overfishing has led to diminishing wild stocks all over the world. As a result, over the last decade there has been a concerted effort to develop the means to culture grouper – both to help relieve pressure on wild stocks and to provide regular quantities of high-quality fish to the market (Frisch, Cameron, Williamson, & Williams, 2016) (Rimmer & Glamuzina, 2019).

One of the key constraints limiting growth of the grouper aquaculture industry is a lack of high-quality fingerlings. This problem is due to two main issues – the limited availability of good quality eggs, and the extremely small size of the newly hatched grouper larvae. Recent developments on cryopreservation techniques for storing tiger grouper sperm in Vietnam could help address the first issue. As for the second, the small size renders the grouper larvae fragile and in need of small live prey of adequate nutritional value.

Where rotifers fall short

While today’s practice of feeding rotifers during the first larval period has allowed for cultivation of various grouper species, the survival rate is usually low and the growth and quality of the larvae varied. To ensure the rotifers have an adequate nutrient composition is not straightforward – they often lack key nutrients such as taurine, vitamin A, Iodine and fatty acids like DHA and EPA. Looking into alternative feed solutions has therefore been a priority.

© CFEED

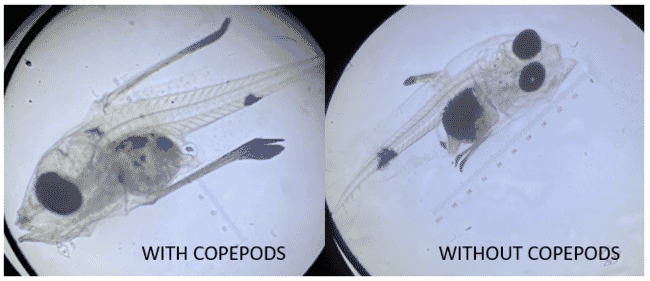

In the wake of this, several studies have appeared showcasing the potential offered by the application of copepods as feeds for larval grouper. For larval leopard coral grouper (Plectropomus leopardus) a tenfold increase in survival, in addition to more rapid development, was observed (Burgess, Callan, Touse, & Santos, 2019) (Melianawati, Astuni, & Suwirya, 2013). Adding copepods to the diet also quadrupled the survival rate of tiger grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus) (Rimmer, et al., 2011). In addition, growth parameters such as total length, body depth and dorsal and pelvic spine length were positively affected, all in all producing more vigorous larvae.

Despite these results, setting up copepod production units has not been an option for most hatcheries, as they require much work and don’t always produce a steady supply. However, due to companies like CFEED* now supplying the Asian market, copepod eggs can be obtained and hatched on demand in a similar way as Artemia cysts. The newly hatched copepod nauplii are just below 100 µm in length, making them an ideal size for the young grouper larvae. This has led to a number of commercial hatcheries starting to incorporate copepods into their feeds. One of these, Eco Aquaculture Asia in Thailand, reported that including copepods in their hatchery feeds had led to stronger and faster growing grouper fry being produced, ultimately helping to increase their production levels.

The nutritional benefits of copepods

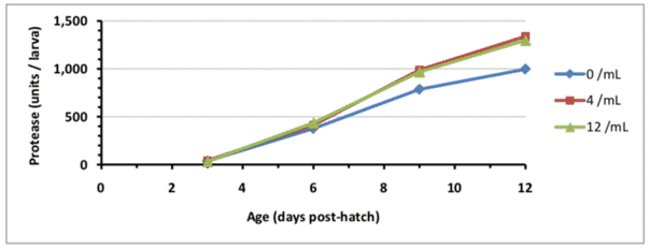

One benefit from feeding copepods comes from their capacity to stimulate enzyme activity in the gut of the grouper larvae. For tiger grouper a significant increase in enzymatic (protease) response was demonstrated when copepod nauplii were added to the diet, raising the enzyme activity by 25.8 percent compared to traditional live feeds such as rotifers and Artemia (Rimmer, et al., 2011). Even the addition of a small proportion of copepods was sufficient to stimulate this increase. A similar result was seen for larval coral trout, where both a full and a partial inclusion of copepods increased the activity of the digestive enzymes protease, amylase and lipase significantly (Melianawati, Pratiwi, Puniawati, & Astuti, 2015).

© Rimmer, et al., 2011

Another factor seen to be important for grouper larvae is the fatty acid composition of the live prey. In addition to ARA and EPA, the fatty acid DHA has been identified to be of crucial importance for tiger grouper larvae (Rimmer, et al., 2011). When starved, the larvae conserve this to a higher degree than other fatty acids, indicating how essential it is for early larval growth and development.

This could provide another reason why copepods boost survival, growth and development of grouper larvae, as they naturally contain high level of these fatty acids, commonly reaching over 25 percent of the total lipid content (van der Meeren, Olsen, Hamre, & Fyhn, 2008). They are also known to have a naturally high content of taurine, astaxanthin, vitamin C and iodine, and contain 60-70 percent protein.

© CFEED

In nature, copepods are considered the most important group of zooplankton, forming a vital link between primary production and fish larvae. Studies on gut content in larvae of coastal tropical fish revealed that the majority relied on copepods as their primary source of feed (Sampey, Mckinnon, Meekan, & Mccormick, 2007).

Providing a way for fish producers to offer their fish larvae the diet they would prefer in the wild has been one of the goals for the Norwegian based company CFEED. With bio-secure, indoor production of the calanoid copepod Acartia tonsa, they can provide a stable, commercial supply of copepod eggs to hatcheries around the world. These eggs can be hatched on demand, providing a nutritionally balanced prey option for the fish larvae. The small size of the newly hatched nauplii makes them ideal feeds during the most sensitive stage for the grouper larvae. In combination with a nutritional composition that is ideal for first feeding, this easy solution of introducing copepods into commercial grouper aquaculture could greatly improve the productivity of hatcheries in the future.

*The Fish Site is owned by Hatch, which has invested in CFEED, but we remain editorially independent.