One of the most animated discussions in the global aquaculture community undoubtedly remains the industry’s dependence on brine shrimp (Artemia) to feed many fish and shellfish species while in their larval stage. Paradoxically, it might well be that the very thing that has made large-scale aquaculture possible is also one of the greatest impediments for the industry’s further growth.

In a series of articles published on the INVE Aquaculture website and released to selected aquaculture media, we are gathering the thoughts of some of the leading Artemia experts and pioneers, looking at past, present and future Artemia feeding strategies in fish and shrimp hatcheries worldwide.

Historical importance of Artemia

The larvae of shrimp and most marine species have to be offered a live food, whereas chicken and cattle accept inert diets throughout their lifecycle. And because culturing of the zooplankton (the natural food of fish and shrimp larvae) was either commercially unfeasible or technically hard to realise, the efforts of early aquaculture pioneers were hampered by inadequate larval food supplies.

Patrick Sorgeloos, founder and former director of the Artemia Reference Center at Ghent University, explains: “The beginning of a solution to this problem came from the discovery by Seale (1933) in the USA and Rollefsen (1939) in Norway, that newborn fish larvae could be fed with the 0.4mm nauplius larva of brine shrimp Artemia. A small crustacean species that thrives in salty, desert-like conditions where few microalgae and bacteria survive. This discovery was particularly interesting because of the unique reproductive system of this fascinating crustacean species.

“For the species to survive in its typically harsh environment, Artemia have developed the ability to produce ‘winter eggs’. These ‘eggs’ are in fact cysts containing embryos that enter a period of dormancy – this is an intriguing biological event in which an organism remains in a deep sleep and stops metabolising, only to wake up when conditions are favourable. This means that these encapsulated, inactive embryos can be stored for a long time and simply have to be incubated under the right conditions to produce free-swimming nauplii that are very well accepted as a food source for fish and shrimp larvae. All of a sudden aquaculture had theoretical access to a source of live feed that could be produced on demand.”

Development of the Artemia market

The first true commercial supply of Artemia cysts came from salt ponds in the San Francisco Bay Area and later from the Great Salt Lake in Utah. The latter remains a source for sustainably managed, quality cysts up to this day.

Very soon, however, the increasing demand exceeded the yearly harvest of approximately 30 to 50 tonnes. From the late 1960s on, there was an aggravating cyst shortage, and the hatching quality of the available cysts became less and less reliable. It was only after the FAO’s Technical Conference on Aquaculture in 1976 in Kyoto that the situation started to change for the better.

Mandated by the FAO, and following on from his earlier work at the University of Ghent, Belgian biologist and researcher Patrick Sorgeloos led a number of initiatives from 1978 onwards to try to future-proof the limited global Artemia supply as a resource for professional aquaculture.

This work later resulted in the foundation of Artemia Reference Center and of INVE Aquaculture.

The work done by Patrick Sorgeloos and his team focused on finding solutions for the major impediments for the further development of Artemia use in aquaculture:

The need to explore new natural sources of Artemia in Europe, Asia, North and South America and Australia and the introduction of brine shrimp in other suitable habitats such as north-east Brazil, Vietnam and China.

Improving cyst quality by developing new harvesting techniques, such as harvesting at the water surface instead of at the lake shores (where dirt particles build up between the cysts and the repeated hydration-dehydration cycles affect the hatching quality and energetic content of the embryos).

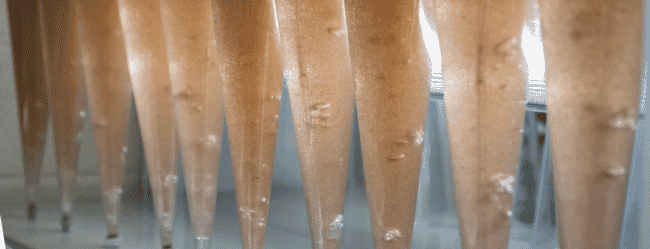

Improving yield reliability by developing standard Artemia hatching protocols that establish the optimal conditions for the nauplii to hatch successfully and simultaneously.

Classifying and fingerprinting the differences in size, hatching performance, growth rate, nutritional value etc of Artemia cysts coming from different strains, locations and even harvests.

From “raw” to processed Artemia

For a long time Artemia cysts were simply harvested from the shoreline and distributed as a raw product. But due to seasonal and regional variations, differences between subspecies and contamination of the product with sand and other external substances, the efficient and safe use of Artemia as a live feed required a more structured and responsible approach.

Alessandro Moretti , product manager for fish hatcheries and Artemia, INVE Aquaculture, explains: “Decades of intensive research and development have led to the sophisticated live-feed resource aquaculture knows today: a carefully processed product, namely the dry cysts that produce live nauplii within 24 hours of incubation.

"Thanks to superior processing and fingerprinting techniques, cysts can be packed and labelled according to their specific characteristics – such as size, hatching capacity and nutritional value, regardless of their strain or origin.

"Advanced and patented technologies make it possible to break the embryos’ dormancy on demand for optimal hatching efficiency, to easily separate the empty cyst shells from the nauplii after hatching and to secure the Artemia’s biosecurity and energetic content with innovative processes and enrichment (Selco) products.

"This means that in an ideal situation every hatchery can procure the exact Artemia that is most suited for its specific application needs, without having to dread any kind of unpredictable outcome.”

Current situation and bottlenecks

Today we are at a point where the world’s most interesting Artemia resources have been identified and are exploited to their full capacity while maintaining a sustainable harvesting rate. Together these sources provide a global supply of more than 3,000 tonnes per year. This is a major industry bottleneck on its own. Because, unlike global aquaculture which is expected to keep on growing exponentially, the Artemia supply will remain more or less stable at its current capacity.

Geert Rombaut, R&D manager, INVE Aquaculture, explains: “For aquaculture to keep on growing using the available Artemia supply, the industry will have to take on the challenge of using Artemia as efficiently as possible. This requires adequate knowledge and application strategies.

“We will elaborate further on this in some of our upcoming articles.”

Patented technologies in aquaculture: blessing or curse?

The considerable ongoing investment in the R&D of new technologies continues to open up exciting possibilities to improve the management and productivity of hatcheries and farms worldwide. However, to protect this investment, the companies investing in these new innovations often patent the technology. How should we look at this as an industry? The discussion arose when Benchmark Holdings (representing its subsidiary INVE Aquaculture) won a case before the IP&IT court in Bangkok to protect its patents relating to its Artemia hatching technologies.

The company successfully prosecuted infringement of its patented technology in Thailand. In this case, the patents specifically applied to technology that allows INVE to break the naturally long and unpredictable dormancy of certain Artemia cysts. The patented treatment elevates these cysts’ normal hatching percentage of approximately 20-40 percent to over 80 percent and therefore has brought enormous benefits to INVE Aquaculture’s customers and the market.

As Philippe Léger, CEO of INVE Aquaculture, concludes: “We have been pioneering in aquaculture for more than 35 years. Needless to say, that since then countless hours of scientific work and considerable financial resources have been dedicated to the benefit of our industry and of our customers – aquaculture farms and hatcheries worldwide. We have an obligation to ourselves, to our shareholders and to our customers to protect this investment in the future of aquaculture. It is the only way that we can guarantee the effectiveness of our innovations in the field, and the only way that we can keep the development of new breakthroughs viable.”

This article, which originally featured in Asia Pacific Aquaculture, has had input from Patrick Sorgeloos (Artemia Reference Center, Ghent University), Philippe Léger (CEO, INVE Aquaculture), Geert Rombaut, R&D manager, INVE Aquaculture), Eddy Naessens (product manager for shrimp hatcheries, INVE Aquaculture), Alessandro Moretti (product manager for fish hatcheries and Artemia, INVE Aquaculture.