Sea lice cost the Atlantic salmon industry an estimated $1 billion of losses each year

Can you tell me a bit about your own experience with sea lice?

In my first role as a fish health manager with Marine Harvest [the previous name for Mowi] I worked initially with new methods of treating sea lice, improving the efficiency of bath treatments and timing intervention to prevent the development of egg-bearing females. I was able to supervise many of the first farm treatments with new medicines such as Azamethiphos, cypermethrin and hydrogen peroxide. The overall effectiveness and safety of the treatment medicine had to be assessed to lead to a full market licence.

At an early stage I was able to work on stocking wrasse in salmon pens as a biological control of sea lice, and in recent times, of course, I was rearing cleaner fish at the Ardtoe marine hatchery and working on welfare and Operational Welfare Indices for wrasse and lumpfish. In the early 1990s I was fortunate to work with the late Gordon Rae and Andrew Grant linking Marine Harvest and McConnell salmon in the first salmon farm management agreements on fallowing, single year class stocking, synchronising treatments and exchange of information between companies. This revolutionised sea lice control within specific hydrographic zones, such a fjord/loch systems, and broke the cycle of sea lice infestation with immediate beneficial results. This led to work on a national sea lice treatment strategy for Scotland and, along with other health managers from other companies, we worked on strategic treatments. This entailed all companies in specific management zones treating salmon for sea lice simultaneously.

Treasurer helped develop the sea lice counting and reporting system the industry uses today

This later developed into integrated sea lice management, which is described in the book. I was fortunate to be involved in the development of the sea lice count and reporting system and we collected many years of farm data. This was analysed by the late George Gettinby and Crawford Revie of Strathclyde University to understand, through epidemiology, the environmental and management factors that affect the cycle of sea lice abundance and effects of treatment intervention.

What inspired you to edit a new book on sea lice?

The new book is called Sea Lice Biology and Control and my co-editors are Ian Bricknell, Professor of Aquaculture at the University of Maine, and James Bron, Professor of Aquatic Animal Health at the University of Stirling. It is 29 years since the first dedicated book on sea lice biology and management Pathogens of Wild and Farmed Fish: Sea Lice (Boxshall and Defaye, 1993).

We felt that the main requirement for the new book was to bring all the knowledge about sea lice biology and treatment methods into one single source of reference. We had all been involved in sea lice research and management over a long period. I was involved in the first sea lice conference on the biology of sea lice and control in 1992 in Paris, organised by Geoff Boxshall and the late Andre Raibaut. That was a unique moment as it brought researchers and industry members together for the first time to try to understand the biology of sea lice and their impacts on aquaculture.

The new publication has 25 chapters and more than 60 contributors

Since that time the methods to control sea lice have changed dramatically, and the potential interaction of wild and farmed salmonids has developed as a source of debate. However, at the same time, there has been a wealth of new advances in knowledge of sea lice biology, examination of resistance development to medicines, and in sea lice treatment methods. A dedicated book on sea lice was therefore long overdue.

Who are the key contributors?

The book has over 60 contributors and the leads on each of the 25 chapters were critical in assembling a team in each discipline to give a good overview of each subject. Each chapter has a key part in understanding sea lice biology. The chapters are in logical sequence and all carry key conclusions and suggestions for future research and development.

I suppose the key contributions for readers will follow their interest as researchers, farmers or regulators or on interaction with wild fisheries. For farmers, the chapter on physical control methods will give a comprehensive and interesting review of the various forms of physical control that are now being used widely and replacing medicines in many cases. The regulatory licensing and use of medicines is an area unfamiliar to many and the regulations applying to sea lice medicines in various salmon producing countries are described.

New subject areas, not covered by the sea lice book of 1993, will have considerable interest – such as the chapters on sea lice vaccines, genomics, sea lice physiology and epidemiology of infection.

Physical lice barriers like semi-closed containment systems are being adopted in lieu of medicinal treatments © Cermaq

Who is the target audience?

The first section deals with the biology of sea lice and so will interest biologists and researchers. However, understanding the biology of sea lice is critical for all who attempt to control sea lice numbers, and to understand their impact.

The second section looks in detail at the various control methods – medicinal, mechanical, biological or preventative – and so will be of interest to fish health staff and farm staff and managers. There is also a lot of sound science in this section that explains how resistance to medicines develops, how functional feeds work and the basis of selective breeding for salmon resistance to sea lice.

The final section on the global impacts of sea lice will be of interest to those who work in wild fisheries and an extensive overview is given of wild-farmed fish interactions.

What makes sea lice such a perennially hot topic in salmon farming?

The sheer persistence of sea lice to new control approaches! The control of sea lice is the largest health cost for salmon farming. Sea lice are adaptable and have developed resistance to medicines. That is why the focus has moved to genomics to understand the mechanisms of resistance. Also there is greater emphasis on preventative methods, mechanical methods, the use of cleaner fish, and new treatments such as functional feeds and potentially vaccination and genetic selection of sea lice resistant salmon families. There are many anthropogenic and environmental factors affecting wild salmonid stocks, but sea lice have been quoted by objectors to fish farm developments.

How much does the salmon industry spend a year on combating lice?

The global figure has been estimated by several commentators at around $1 US billion. This includes treatment costs, health input, medicines, but the major impact will be on salmon growth rates, reduced appetite and loss in biomass and shortfall in production.

Sea lice cost aquaculture in control methods and medicines, in economic damage and also in public perception, with aquaculture expansion being made more difficult by planning and regulatory controls. There are the obvious costs of medicines and technical veterinary and health expertise and staffing and logistical support, such as wellboats and the cost of treatments such as thermolicer and hydrolicer, and adaptation of nets and applying skirts or snorkel cages. Also, there are costs of downgrade at harvest.

What other farmed fish are significantly impacted by lice?

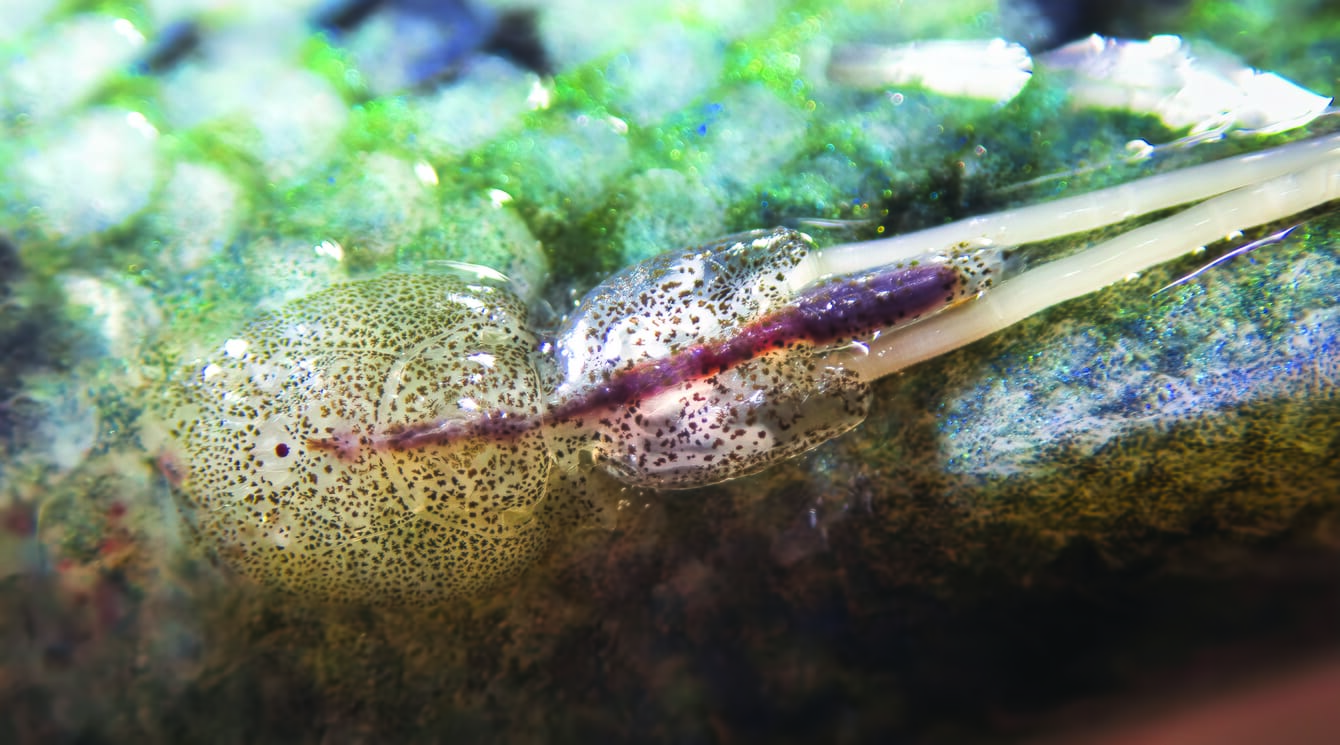

The emphasis in the book is on the main sea lice species that are a threat to farming of salmonids and these are Lepeophtheirus salmonis and Caligus elongatus in the northern hemisphere, and C. rogercresseyi in Chile. However, a chapter in the book by Dr Ken MacKenzie lists and describes over 40 sea lice species that have been recorded from farmed fish worldwide.

Snorkels are another example of a preventative measure against sea lice © Frode Oppedal

This includes almost all geographical areas – including the Mediterranean, South Africa, the west coast of Africa, the Middle East, south east Asia, Australia, the north east Pacific, and the south east Atlantic. Sea lice have infected many cultured species including black sea bream, yellowtail amberjack, common dentex, groupers, striped trumpeter, mullets, milkfish rabbitfish and Atlantic halibut.

How has sea lice control evolved over the years?

The book describes and analyses in detail the first methods of sea lice control. These were medicines in Norway and in Scotland that were applied as bath treatments after the pens had been enclosed in a tarpaulin and oxygen supplied. Preventative methods then followed, with site fallowing and management agreements to follow single year class stocking of smolts in fjords and sea lochs and in coastal areas this helped break the cycle of infection.

Over time and with the development of reduced sensitivity new medicines had to be explored. Oral treatments such as Emamectin benzoate were introduced in the late 1990s but resistance to these also developed. Emphasis shifted from 2015 to mechanical methods, first in Norway, and this has seen a considerable reduction in medicine use. Management tools such as area and national treatment strategies and adoption of an integrated pest management approach to sea lice control have given benefits. The use of cleaner fish on a larger scale in the last 10 years and the focus to preventative methods has also been a major shift.

The aquaculture industry is exploring new treatment methods for sea lice like functional feeds, sea lice vaccines and selective breeding

What emerging tools do you see as having the greatest potential to control sea lice – both in the short term and in the more distant future?

Novel treatment methods such as functional feeds – but also selective breeding and a sea lice vaccines in the longer term – are being explored. In the immediate term I can see further use of mechanical methods and an extension of preventative measures. These include reducing the opportunities for the infective copepodid stage to encounter salmon with barrier methods such as skirts on pens, snorkel pens, air bubbles from the bottom of the net, and also lights and feeding practices to increase the depth of the fish in the water column. Methods for reducing attachment include functional feeds as mentioned, the use of cleaner fish, and vaccination.