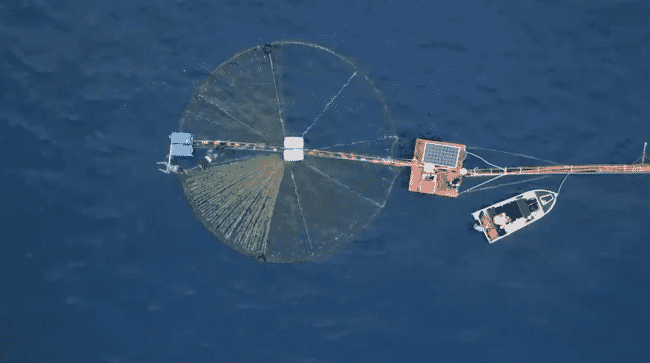

Recent trials suggest that marine permaculture makes seaweed production more efficient by raising the platform during daylight hours and submerging it at night. © The Climate Foundation

Delivering the keynote speech at the Seagriculture Asia-Pacific online conference, The Climate Foundation’s Dr Brian Von Herzen shared the latest updates on its marine permaculture project. Von Herzen showed delegates multiple videos and computer simulations of marine permaculture rigs – flexible platforms that can be seeded with seaweed and then safely raised and submerged beneath the ocean surface as the macroalgae grows. Recent trials suggest that the system makes seaweed production more efficient: raising the platform during the day improves photosynthesis and lowering it below the water at nightfall takes advantage of improved nutrient upwelling.

Though seaweed farming has been a mainstay of East and Southeast Asia’s aquaculture sector, recent research pinpointing the segment’s economic and climate adaption potential has sparked interest beyond its traditional home. For The Climate Foundation, seaweed farming has become a crucial component in their vision for a climate-positive marine economy.

In Von Herzen’s view, farming seaweed at scale can help the world meet its carbon capture and sequestration goals. Scaling production could also help regenerate ocean ecosystems – returning them to their pre-industrial levels of biodiversity and resilience.

During his speech, Von Herzen showed delegates results from the third phase of trials of the novel marine permaculture system at seaweed farms in the Philippines. The submersible platforms grew eucheumatoids and other hitchhiking seaweeds over a 1,000 m² area in 2022; and there are plans to scale the system to cover full hectares in 2023.

According to Von Herzen, the recent trial shows that marine permaculture increases seaweed growth and doesn’t deplete surface nutrients in the ocean’s upper layers. Results also indicate that the system doesn’t upwell stored ocean carbon – it actually facilitates new carbon sequestration. As an additional bonus, he noted that the ability to submerge the platform below the ocean’s surface makes it storm-proof.

The Climate Foundation used marine permaculture arrays to grow eucheumatoids and other hitchhiking seaweeds over a 1,000 m² area in 2022.

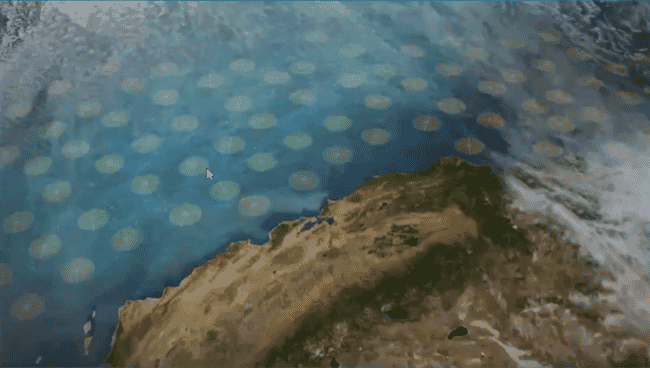

Von Herzen told delegates that the real potential for marine permaculture lies in offshore seaweed production, especially for seaweed species in Southeast Asia. Moving offshore would allow the NGO and local farmers to incorporate more ocean area into farming plots. He estimates that there are more than 200 million km² of aggregate ocean area that could be partially transformed into productive seaweed habitats by using the novel system.

As the NGO enters phase four of its trials, Von Herzen expects development costs per hectare to decrease, as its climate co-benefits grow. He told delegates that reaching this level of production could help ameliorate damaging climate trends like marine heatwaves and ocean acidification. It could also revolutionise Southeast Asia’s seaweed sector – making marine permaculture an agent of ocean restoration.

The cascading impacts of rising ocean temperatures

Ninety-three percent of the heat captured by greenhouse gases is stored in upper ocean strata. As industrial emissions increase, ocean temperatures have been rising as well, creating a slow-moving disaster for marine ecosystems. Escalating temperatures can make marine stratification – the temperature difference between ocean depths – more pronounced. This in turn impacts current circulation, nutrient levels and phytoplankton populations that support entire ecosystems. The increased heat, intense stratification and reduced nutrient currents reinforce one another, making the aggregate climate impact more pronounced. The scientific community has noted that the tropics are on the front lines of this impact, and ecosystems are beginning to degrade.

“Our coral reefs and tropical seaweed production [are] on the front lines of climate disruption within one degree of mortality every summer,” Von Herzen said. Marine heatwaves are damaging Southeast Asia’s ocean habitats and putting pressure on the region’s seaweed and aquaculture industry.

Von Herzen cited recent data showing that warmer water temperatures in the Pacific made macroalgae more susceptible to disease threats. He also noted that decreased cool water and nutrient upwelling from the heat makes it harder for seaweed cultivations to thrive. Indonesia’s eucheumatoid sector has seen a steep drop in production since 2015 – and kelp forests near Tasmania and California are declining as well.

Despite the marine heat crisis falling firmly into the “doom and gloom” climate story, Von Herzen and his colleagues theorised that they could harness the ocean’s natural systems – and seaweed ecosystems in particular – to ameliorate it.

Decreased cool water and nutrient upwelling from marine heat waves and climate change makes it harder for seaweed cultivations to thrive. © Kelp Blue

Making waves with marine permaculture

Seaweed ecosystems spark a lot of interest because they’re among the most productive habitats on the planet. Macroalgae species store carbon and nitrogen in their biomass as they grow, improving the surrounding water quality and addressing the increased acidification that comes with ocean warming. Macroalgae also provide shelter and food for marine species, allowing areas to retain their biodiversity.

There’s a compelling economic case for farming seaweed as a crop as well. The plants require no feed inputs or fertilisers and they can be grown in diverse ocean environments. Seaweed farming has been a key economic engine for coastal communities across Asia and Oceania for decades – making the recent production declines both a worrying economic and ecosystem trend.

As Von Herzen sees it, learning how to counteract declining farm landings is key to bringing the other co-benefits of seaweed aquaculture online. He explained that seaweed beds can fix multiple kilograms of carbon per square metre of growth every year. If these habitats – either farmed or wild – account for hectares of the marine environment, they could each remove tens of tonnes of excess carbon from the atmosphere each year. Producing seaweed by the hectare could also help address marine heatwaves, improve biodiversity, and provide livelihoods for coastal communities.

Von Herzen needed to find a way to protect – or re-create – the natural nutrient upwelling and cooler water that facilitates seaweed production. He drew inspiration from ocean waves and designed the marine permaculture system to use their constant ebb and flow to create a water circuit to fertilise seaweed.

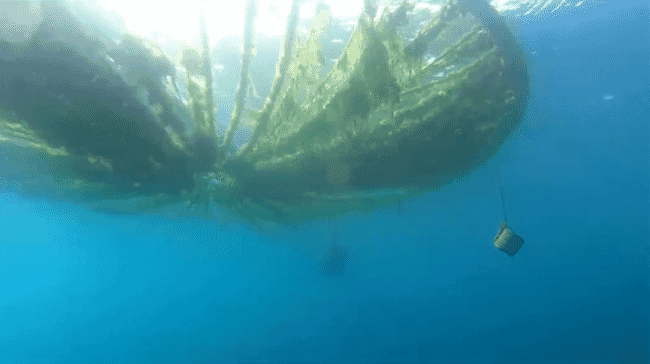

Marine permaculture arrays were originally developed using regenerative upwelling, today most arrays use a version of deep cycling, in which sunlight acts like a sponge and absorbs sunlight during the day. The platform is lowered at night below the onset of the thermocline, for the seaweed soaks up nutrients during the night. At sunrise, the platform rises to the surface, enabling the seaweed to soak up sunlight and carbon dioxide in the top metre of the sea, which is in daily regular equilibrium with the atmosphere and its carbon dioxide. Thus the seaweed is able to absorb deep water nutrients and surface carbon in a way that provides a true blue carbon sink with marine permaculture arrays. This is one of a number of methods available to the industry,

The arrays also host mini-ecosystems as the seaweeds thrive – ensuring that the area does not become a monoculture. Once the marine permaculture array has helped the ocean water regain its natural rhythm of overturning circulation, kelp and eucheumatoids can grow and seaweed forests reappear.

This “deep cycling” raises and lowers the submersible seaweed platforms on a diurnal cycle: lowering at night to give the seedlings greater access to micronutrients and phosphates in the water, and raising during daylight hours so the plants can utilise sunlight and absorb carbon dioxide from upper ocean strata.

“The seaweed acts like a sponge,” Von Herzen told delegates. The greenhouse gas impact is potentially enormous. "The total amount of emission reductions and carbon removals could approach 30,000 tonnes per square kilometre per year,” he said. This is comprised of 8,000 tonnes per square kilometre per year of carbon removals and up to 22,000 tonnes of avoided emissions when seaweed products are used on agriculture to reduce the use of NPK fertiliser. Of the 22,000 tonnes of avoided emissions, 12,000 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent is avoided from conventional fertiliser manufacturing.

He also told delegates that the system could sink approximately 8,000 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent in the deep ocean as portions of seaweed growth detach from the platform and sink to the abyssal sea floor. The remaining seaweed serves as fish habitat and is later partially harvested and processed for downstream industries.

Next trials and next steps

As The Climate Foundation enters its fourth phase of trials with marine permaculture, it’s hoping to scale the arrays to a hectare in size and verify its business model before embarking on a commercial rollout. The current trial will deploy 10,000 m² (one hectare) of arrays in 2023 and the NGO is looking to move the rigs offshore. Von Herzen expects the platforms to provide hundreds of tonnes of harvested seaweed per year.

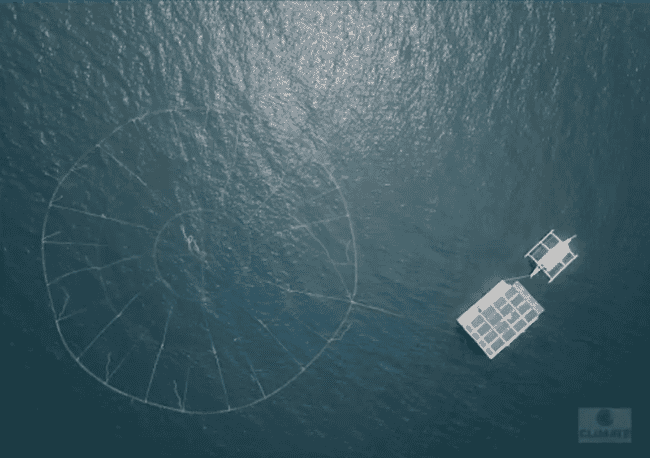

The Climate Foundation is entering its ninth round of trials with marine permaculture. © The Climate Foundation

The NGO’s team in the Philippines is exploring ways to build larger submersible platforms as they quantify the production benefits of the marine permaculture system. Farmers are reporting a fourfold jump in the system’s seaweed growth rates, from May 2020 to March 2021. The arrays also show strong monthly growth in low-nutrient waters. The group is currently using the rigs to provide seed material for local seaweed farmers – addressing a key chokepoint in the seaweed value chain.

The next step is to take advantage of the declining costs of development and deployment per hectare. “Our first hectare development cost $3 million,” Von Herzen said, but after ten hectares, it decreased to $1 million per hectare. He believes that when the company develops 100 hectares, costs will fall to $500,000 per hectare. The first part of phase four (their ninth trial with the system) is projected to cover 15 hectares and cost $25 million.

Von Herzen hopes that the system can be deployed offshore in the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of different countries as they scale. He told delegates that his vision involves using marine permaculture arrays to grow seaweed the way terrestrial farmers grow crops in the US and Canadian prairies. He wants to create offshore seaweed circles that restore the ocean’s nutrient circulation and re-wild marine habitats.

In his view, Southeast Asia holds tremendous potential for EEZ development with marine permaculture arrays. Many nations in this region are island archipelagos with extensive coastlines. Von Herzen estimates that 200 million km² of empty ocean area can be made amenable to marine permaculture.

Von Herzen hopes that the system can be deployed offshore in the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of different countries as they scale. © The Climate Foundation

This assessment sounds incredibly optimistic – 200 million km² is nearly twice the area of the Atlantic Ocean. There are also outstanding questions on how seaweed farming at the projected scale could impact nutrient and carbon cycling in the marine environment.

However, there are plenty of reasons for Von Herzen and his colleagues to remain hopeful. Marine permaculture has received recognition from legacy publications like The Washington Post and The Economist and groups like the Sustainable Ocean Alliance. The Climate Foundation is also the only nature-based ocean group to win the X-Prize (Milestone Award) for carbon removal. If their newest round of trials maintains their winning streak, we may have a feasible way to farm seaweed, sequester carbon and restore marine habitats.

Seagriculture Asia-Pacific was held from 8 to 9 February 2023.