The project is a collaborative effort involving Fish Welfare Initiative (FWI) and Sage, a cafe and store chain in Hyderabad, which is FWI’s first corporate partner.

Improvements in welfare have included greater pond preparation, more feed management and reducing stocking densities. Most recently the team at FWI visited Sage to follow up on their progress and trial a higher-welfare stunning and slaughtering process.

Neither Sage nor the FWI team had much practical knowledge of stunning pangasius in the Indian context, and they agreed to work together to test and refine this process.

“Although slaughter is often challenging and almost invariably involves some suffering, we believe our work with Sage is a critical step towards implementing pre-slaughter stunning in a country where, to our knowledge, it has never been practiced before for fish,” explains Jennifer Kirsch, director of international programs at FWI.

Why stun fish before slaughter?

Fish are sentient beings capable of feeling pain and distress. By itself, this necessitates an improvement of slaughter practices to reduce induced distress and pain for a large number of individuals. While slaughter only makes up a comparatively small part of fishes’ lives (ie, a few minutes to one hour), the inflicted pain can be particularly intense. On most Indian fish farms (as in many other countries), during capture, fish are usually crowded in nets for several hours before asphyxiating in air or on ice.

This process causes severe distress and pain. Research in the past few decades has been uncovering more welfare-friendly alternatives to conventional fish slaughter with the goal of minimising pain and distress. Stunning prior to killing is a promising method to desensitise the animals and avoid pain in their last minutes of life.

Fish are said to be desensitised if spiked or stunned percussively or electrically before killing. Percussive stunning is done by delivering a strong hit on the fish’s head to “knock them out” by disrupting brain activity. For electrical stunning, fish are immersed in electrically charged water or electrocuted in a dry chamber, inducing a cessation of brain function. In a similar way, spiking the brain directly causes irreversible damage to brain functions and thus the ability to process painful stimuli. These methods aim to make fish fully immobile and unconscious before bleeding them out and thereby killing them.

The process

Discussing the possibilities for stunning with Sage’s staff, FWI recommended that they stun fish percussively. Electric stunning devices are usually stationary and made for stunning a lot of fish (several tens or hundreds of thousands). The equipment needed is expensive, and only trained personnel can operate it safely. This makes its use challenging in rural and poorer regions.

“Some forms of electrical stunning have also been criticised as being ineffective at rendering all fish unconscious, due to differences in their size and physiology, and is believed to negatively affect flesh quality. Considering the small number of fish and the ability to handle them individually, percussive stunning, in our best judgment, appeared to be most promising,” Kirsch explains.

“After extensive research and conversations with experts, we recommended a three-step stunning and killing process to ensure minimal suffering for the fish involved. Three of our team members went to Sage to oversee the process,” she adds.

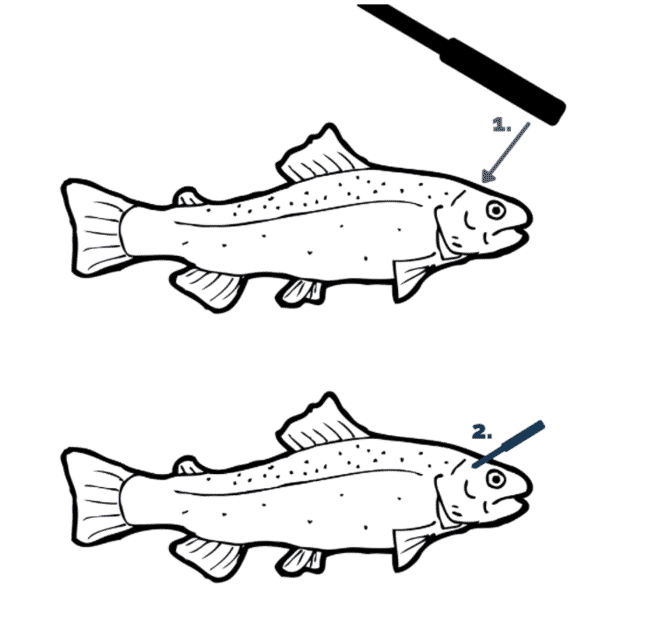

First, fish were percussively stunned by hitting them on the head with a metal pole. The effectiveness of this method was judged by checking the fish’s unconsciousness through assessing the eye-roll reflex. Percussive stunning ensured that all fish were desensitised (ie couldn’t feel pain) before continuing the killing process.

“After the successful stunning, fish were spiked with a needle in the middle of their brain to achieve brain death and the resulting inability to process painful stimuli. In theory, percussive stunning is sufficient when fish are killed before regaining consciousness. We used the spiking as a secondary measure to prevent the fish regaining consciousness and the ability to feel pain at any point,” explains Kirsch.

While the fish were still unconscious, their gills and main artery were cut to let them bleed out.

“Advising Sage’s team in this process was graphic work, as is most work involving animal slaughter, and despite our best efforts it was still an imperfect process. We intend to work with more corporations like Sage to further refine the stunning process, and we firmly believe that the solutions to these problems will necessarily involve rolling up our sleeves and interacting closely with them,” explains Kirsch.

Over the course of that day, Sage staff caught 24 pangasius and used the process described above for all of them. From their observations, five of the fish were desensitised with a single hit on their head and showed immediate unconsciousness when assessing the eye-roll reflex. For the remaining 19, Sage staff were only able to confirm unconsciousness after two to four hits on the fishes’ heads.

“It seems that the biggest challenge of percussive stunning is to desensitise the fish with a strong enough, single hit on their head without requiring a second or third. Having to hit fish several times creates immense distress and pain for the fish and, thus, percussive stunning is only a proper stunning method if done perfectly – which is often difficult. The steps following the stunning were easier to implement, and fish were successfully spiked and bled out before regaining consciousness,” says Kirsch.

“To our knowledge, this has been the first attempt to stun finfish before slaughter in India. While the process was not yet perfect, some fish were spared unnecessary, prolonged suffering during this killing process. We think that this stunning method could be used by small-scale fish farmers across India to ensure high animal welfare and related benefits like better product quality. Nevertheless, for large commercial applicability of percussive stunning, the effective blow to cause instant unconsciousness will require some kind of automatisation and standardisation. This can only be achieved by further collaboration between researchers and farmers, alongside proper training to decrease the likelihood of doing more harm than good to the fish,” she adds.

“We are grateful to SAGE for pioneering this space to get closer to a pain-free killing process for their fish. We will continue to work together to refine the stunning process, both with Sage and our other partners in India,” Kirsch concludes.