Erik Jan Lock is co-ordinating the four-year offshore aquaculture research project

As Europe’s offshore renewables sector grows, so does the importance of assessing and addressing the opportunities and threats it poses to marine industries and biodiversity. And many people in the aquaculture sector are cautiously optimistic about the potential offered by the increasing numbers of turbines being installed in the seas

One of these people is Erik-Jan Lock, from Norway’s Institute of Marine Research (IMR), who will be co-ordinating the four-year project.

“The blue revolution is on its way, but we need to remember that it is not only aquaculture. Windfarms at sea can take a lot of space and the more efficiently we can use that space the better it is. Aquaculture within windfarms can be a good way to use offshore marine space for green energy and blue food,” he reflects.

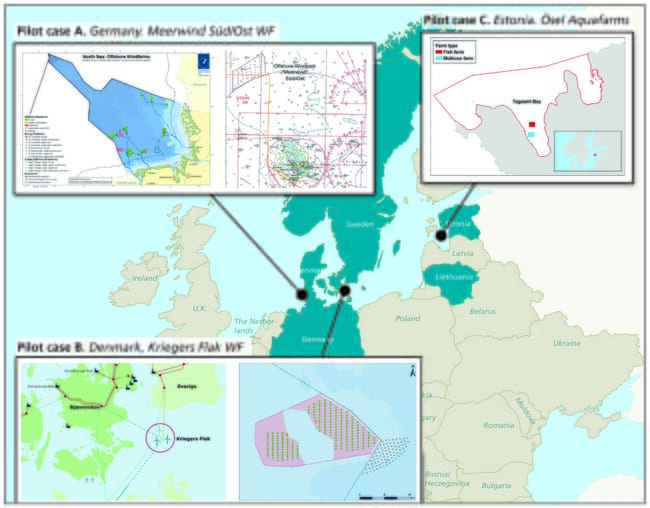

Called offshore low-trophic aquaculture in multi-use scenario realisation (OLAMUR), the project involves 25 partners – from a range of industries and academic institutes, as well as NGOs – and is set to take place across three pilot-scale demonstration sites. One will be in the North Sea, off the coast of Germany’s Helgoland island; one in the Baltic Sea at Kriegers Flak on the east coast of Denmark; and one off the coast of Estonia.

The pilot projects will take place in the North Sea off the German coast, in the Baltic Sea on the East coast of Denmark and off the coast of Estonia

“The sites in Germany and Denmark are operational wind farms and the companies that run them [Wind MD and Vattenfall Europe Windkraft] are part of the consortium and will allow us to establish seaweed and blue mussel farms near the turbines. Meanwhile the site in Estonia is a rainbow trout farm, run by Ӧsel Aquafarms, where we will farm seaweed and blue mussels in an IMTA setting,” Lock explains.

“The reason that we are conducting trials at windfarms in both the North Sea and the Baltic is that the salinity levels and weather conditions are very different in these two locations, which will affect the organisms that we can grow and the technology that we can test,” he adds.

Although the mussel and seaweed lines will be within the footprint of the renewables sites they will need to be at least 200 m from each individual turbine to ensure that the operators can access and maintain every turbine, whenever required. However, the exact details of the farming setups are still to be finalised.

The project wants to grow mussels in the proximity of wind turbines, but the exact details of the farming setups need to be finalised © Offshore Shellfish

“We have discussed various offshore seaweed and blue mussel systems. We’ve not quite finalised which ones to choose yet, but it’s likely that at the more exposed Helgoland site we will use submersible longlines, which can be sunk deeper during stormy conditions to avoid damage,” says Lock.

Indeed, as Lock observes, conditions on the windfarms could require high spec equipment to be used.

“The sites at Helgoland and Kriegers Flak are truly offshore and could be challenging to farm, which is why we’ll be monitoring the wave heights and – perhaps more importantly – the wave frequencies. This will help us construct models for conditions both above and below the water,” he explains.

Meanwhile, some of the other partners in the project will be investigating the impact of three types of artificial reefs which were created when the Danish windfarm was built – boulder reefs from preparing the seabed, scour protection systems and the bases of the turbines themselves. Under the OLAMUR project, the biodiversity at the three types of structures will be compared, and then contrasted to natural nearby boulder reefs.

Wind farm operators who participate in the project will share their environmental data with aquaculture producers

The current project also has the support of the wind farm operators.

“They will provide us not only with access but also with environmental data that they are continuously collecting. In the future the power they produce could be used to charge electrical service boats, for example, but at this stage that is not part of the project,” Lock explains.

A question of scale

Although the current project is on a pilot scale, Lock notes that significant volumes of kelp and mussels are still likely to be produced, which is why they are working directly with commercial mussel and seaweed producers.

And he says that this industry involvement will help to reinforce the potential offered by the locations should commercial production take off in the future.

Although the current project is on a pilot scale, it will likely generate large volumes of kelp and mussels © Greenwave

“At the end of the project we hope we can give an estimate to relevant stakeholders about the potential for farming at different wind parks in the North Sea and Baltic Sea. This will be in the form of a data-based service system that will be set up. Another part of the project will look at life-cycle analysis of the produced biomass – for example the levels of nutrients and CO2 that the farms absorb, what this means for the marine environment and also what it means for the food production chain,” Lock reflects.

Essentially the project should provide a range of valuable information for those considering co-locating aquaculture and offshore renewables.

“The data-based service system will allow a range of stakeholders to find a lot of information about siting and more. As well as the 25 partners there will also be five associated partners, made up of interested stakeholders (such as renewables producers or local authorities) from countries that are not part of this project but are thinking about establishing a similar concept and want to learn more. This increases the chances of scaling up the impact of the pilot project, both during and after the project,” says Lock.

He adds that associated partners will each receive €100,000 and opportunities to visit the sites. In return they will be expected to provide their own perspectives on the opportunities and challenges presented by co-locating aquaculture and offshore wind and work actively on developing a similar concept at their location. The plan is to start selecting associated partners in January 2023.

Lock is looking forward to assessing the implications of a wide range of other possible interactions between the windfarms and the mussels – not least because he thinks that the project is completely unique.

“Wind farms at sea exist and seaweed and mussel farming exists. But if you put these two together there are so many questions that arise. Anything from food safety concerns, like whether microplastics from the blades of the wind turbines end up in the blue mussels; to marine spatial planning, as these activities are normally planned alone not together; to insurance; to regulations, which don’t yet exist for such co-located projects,” Lock reflects.

“Even within the EU there are huge differences in regulation and it might be legislation, not technology that proves the biggest barrier to the commercial development of such sites,” he concludes.