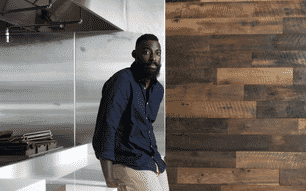

Wolfinger has been called the “Annie Leibovitz of food photography” by the New York Times. He’s photographed over a dozen award-winning books and travelled the world shooting amazing places and cultures through the narrative of the foods they eat.

But he hasn’t always been a photographer. After he finished college, he wanted to find a way to combine his passions for travelling and cooking. He became an apprentice at the famous Tartine Bakery in San Francisco and traded surfing lessons for bread baking tips with its owner. In 2011, he was commissioned to take the photos for the Tartine Bread cookbook. Ever since, he has been one of the most sought-after food photographers in the world – winning this year’s James Beard Award for Best Cookbook Photography for American Sfoglino: A Master Class in Handmade Pasta.

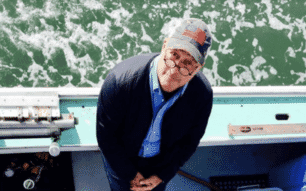

In addition to shooting wineries, restaurants and brands, Eric has helped to build the reputations of some of the most important leaders in aquaculture, travelling the world to capture hatcheries, farms and beautiful plates of reared fish.

© Eric Wolfinger

Can you tell us a little bit about how you got to where you are today?

None of this has been planned. It’s all been completely happenstance. What it drills down to is that, ultimately, I got my start in the kitchen out of a sort of basic love for and respect for food. I wanted work in kitchens because I wanted to tell food stories. At first, I thought I was going to be a writer and I wanted to tell stories from a place that I would respect. I wanted to be some sort of authority, you know, in the kitchen. Soon, I began to realise that there’s more to food than just how you cook and how you prepare it. There’s the whole story of where it comes from. And, I think, one of my main interests – and maybe one of the reasons for the success that I've had – is that I connect the dots. I connect with not just the food, but with the people who are responsible for creating the food – whether it be a chef, a cheese maker, or a fish farmer. These food stories are all human stories and environmental stories.

What are the top three most crucial issues facing people and planet?

We are populating the planet faster than it can sustain us. I think the biggest issue facing us is resource scarcity. How do we, as a society, as a global society, deal with that? How do we divide pie in ways that are regenerative and sustainable? Whether we're talking about allocation of fresh water to arable farmland or fish in the sea, how do we build sustainable systems that can provide for us? We're clearly staring down the barrel of resource scarcity and we need to find creative, regenerative, sustainable solutions to confront it. Once you get into that, you get into climate change, which I think is driving scarcity all over the world. That’s the reason why everyone should be concerned about climate change. Because the bottom line is that your own self-interest is at stake. How can this be ignored? We are witnessing this with the Napa fires. It’s heart-breaking to see this devastation so close to home. The effects of climate change are happening in our backyard.

Personally, I'm revisiting my own consumption choices right now; I'm revisiting a general life approach to choices that I make. I can be part of the solution and not necessarily part of the problem.

Which water body is most special to you?

I grew up in Southern California, two blocks from the ocean. I'm a lifelong surfer. Emotionally, I am tied to the Pacific Ocean, but at the same time it's hard to say that one body of water is more important than another to me. There's a stream in Wyoming that I look forward to visiting every year. Whenever I go back and set foot in that stream, I feel renewed. There's a lake in a part of Switzerland that I'll always remember fondly too.

What are the most crucial issues facing our water bodies?

We're losing vibrant stocks of life all around the ocean. Acidification of the ocean is causing reefs to die off, which is having chain reactions with species that live in those ecosystems. We've fished the oceans to extinction or near extinction. We have scarcity due to overconsumption, which has really scary effects on our oceans.

© Jennifer Bushman

Do you think people are interested in the story of seafood?

I'm all about making a connection with my subject and my viewers, and the projects that fuel my fire are the ones where I get to dive in, get my hands dirty, and come out with an irresistible story. The story of the water farmer is a story that needs to be told over and over again in order to change perception and get the message across. For the last decade, I have been travelling the world to tell these important stories. I believe that everyone is interested in the journey of a hard-working farmer, on land or on water.

Take us back ten years - wild vs farmed and why?

Ten years ago, I shopped entirely by taste – the consumptive choice, I know. But if I liked farmed salmon because it was buttery and mild, I ate it. I ate bluefin tuna with abandon, reckless abandon. Ouch. I skewed more to the wild end of the spectrum; farmed fish just has a certain connotation, some of it earned, some of it not.

What persuaded you of the benefits of sustainable aquaculture?

Nine years ago, I did my first sustainable aquaculture shoot with Verlasso. By then, some of the issues around sustainability in aquaculture were percolating in my head. I'd had the opportunity to write and photograph a story for a local magazine on the controversy surrounding the Drakes Bay Oyster Company. The controversy stemmed from whether or not they were going to have their lease renewed to continue farming oysters. I think they had been farming for over 75 years at Drakes Estero. I must admit that I went into the story with a knee-jerk environmentalist perspective. Why do they need their nets on public land? Get them out of there! Why do we need oyster farming on a national seashore?

I spent two days on the water with the farmers. Needless to say, I came away with a completely different perspective. Oysters are amongst the most efficient forms of animal protein that we can farm, that we can create on planet Earth. They require zero human input. They are filterers. The company employed eight full-time workers and they were producing thousands and thousands of pounds of healthy, fresh seafood. Now, I find aquaculture beautiful. I came away from that experience thinking that all around the Estero are dairy farms that have been grandfathered in; they have grazing rights that have been grandfathered in. But their grazing rights weren’t in jeopardy. It was the water farmer that was on the verge of getting kicked out because of knee-jerk assumptions like my own.

That was my “aha moment”. Sure, we all have assumptions. We've all heard things, but go spend a couple of days on the water and see what is really going on.

Is there a farm that's particularly impressed you?

I would have to say Pacifico Aquaculture – an extraordinary vision from some extraordinary people in just a breathtakingly beautiful place. You could feel their respect of place. When you visited the farm and met the people around it, there was an incredible sense of community – the support that they had from all of the people who lived in the surrounding area and the former fishers who work for them. The area was the North American capital for tuna fishing and now that industry is toast. I am going back to resource scarcity and whether that's human-driven or climate-driven. That moment was human-driven. Seeing a former tuna fisherman, or children of tuna fishermen, working and making a living in aquaculture was a really amazing thing to witness.

What aspects of aquaculture are you still sceptical of?

Verlasso raised one of the most interesting questions that I didn't even know should be a question. How much fish from wild stocks does it take to grow another fish? Depleting wild stocks to feed farmed fish really doesn't work for me. It doesn't work for the world. Aquaculture needs to improve. We need better site placement where there are tides and where the water is moving. We need sustainable feed models and to lower chemical and antibiotic use. Aquaculture has come far in the 10 years that I have been a part of it, but many farms still need to improve.

How do you see the future of fish and seafood?

I want to say that I am an optimist. I have friends who I'm very close to who run a fish restaurant and a wholesale fish business in San Diego. They have a beautiful fish case that has a balance between wild and farmed seafood. I think that, as long as there is balance in how we rear or catch our fish, then we have a sustainable food source for the future. Bycatch and waste can no longer be acceptable. Just because it's not a marketable fish doesn’t mean that we don’t have an obligation to eat it. We shouldn't be wasting anything that we're pulling out of our oceans, and at the same time we can't rely on the wild stocks of the ocean to feed us.