© The Travel Channel

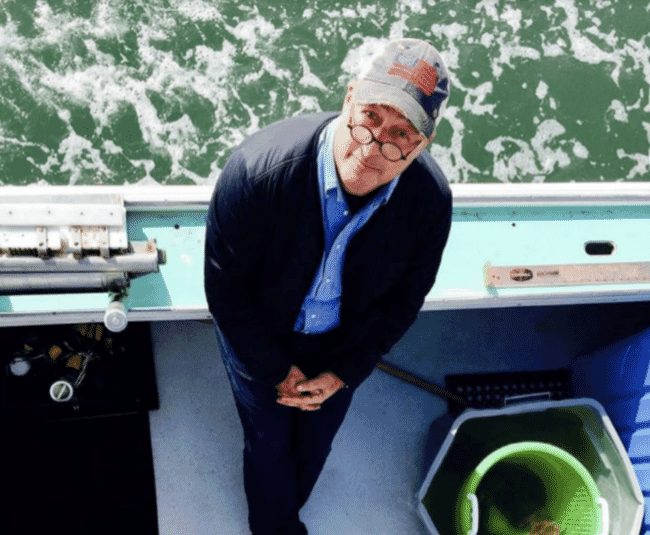

As the creator, executive producer, and host of the Travel Channel’s Bizarre Foods franchise, Andrew Zimmern’s Driven by Food, The Zimmern List, and Food Network’s Big Food Truck Tip, he has explored culture through food in more than 170 countries, en route discovering the value of “water farmers”.

Can you tell us a little bit about how you got to where you are today?

I spent my childhood out on Long Island. We would fish for striped bass, bluefin tuna, and much more, on the weekends. I was a skinny, 60-pound 10-year-old. My dad would hold me by my ankles and lower me between these giant boulders on the beaches on the east end of Long Island – we're talking about boulders the size of a small house that big guys like my dad couldn't reach down into. But if you lowered your kid, you could catch fish. So, he’s got me upside down between the rocks by my ankles, and he's like, “I got you”. It was the most important and foundational connection to the water and to him that I could have ever had.

He also attracted blue crabs by laying out chicken bones that he would let rot in a Ziploc bag all week long. We'd take that week-old, rotted chicken, tie them on strings, and throw them out into the estuaries on the other side of the dunes, where the salt and freshwater mixed. If you slowly pull the strings, the blue crabs couldn't catch up to them to get the chicken. They would come on shore! We would catch them in nets and throw them in a cooler. We would go out to Barnes Landing and the bay between the Two Forks and dig for clams every week. We would set out lines at night for eels in Three Mile Harbor. Nowadays that's called foraging, right?

I believe that food and our relationship to it has been revealed to be something of incredible value – like gold in a miner’s pan. Anthropologically. Sociologically. Civically. Politically. Every which way. I now see food as a magnifying glass, as a lens, through which to view so many things, learn so many things, and interpret so many things.

What’s been your most memorable aquatic experience?

When I was about eight or nine, in 1968 or 1969, my mother took me down to the beach at like five in the morning. We watched the fishermen pull these white long boats with eight sets of oars on them with huge nets piled high into the ocean. They would row out through ten-foot surf in the early morning hours. It was so dramatic – like something you would see in a movie! Once to the flat water in the swells, maybe a half mile offshore, they would drop their nets in giant half-moon shapes. Then, they would rapidly row a half mile parallel to the shore, pulling in the nets that they had laid out at five or six o'clock the night before. After this herculean effort, in the boat would lie thousands of pounds of fish in their nets. I asked my mom “Why are we watching this?” She said “because in a couple of years, this isn't going to exist anymore and I want you to pay attention”.

What are the most crucial issues facing the aquatic environment at the moment?

With our oceans over 90 percent depleted or fished to capacity, we need to think about how to produce an economy, a true blue economy, around a balance of aquaculture and wild capture fish, in order to be able to bring the price down and create more access to fresh fish and seafood for everyone.

Imbalances in our system are everywhere. If corrected, it would keep more money at home, support more domestic water farmers, keep more fish, increase the amount of fish on American’s plates, and we would be healthier. The trickle-down effect of fighting ocean depletion and bringing access to more sustainable nutritious ingredients would be enormous. What's lagging behind is education and communication to the American consumer about these issues, so they can make smarter choices at the grocery store. We need to expand, not shrink, the presence of seafood in supermarkets.

© The Travel Channel

Do you think that people are interested in the provenance of seafood?

I grew up in this environment where seafood was the most treasured thing. We understood the balance of nature and where our food came from. I started cooking in kitchens the summer I turned 14 and I've never stopped. I'm 59. That's 35 years that I have been in kitchens. I've watched the seafood industry change over those years. We have watched the culture change, the industry shift. In some ways for the worse, some ways for the better. I want to go to the National Supermarket Owners Convention (is there one or something like it?) and stand on stage yelling, “Bring the seafood counter back! Fill it with real seafood, have people tasting and sampling”.

Let's get some passion and some right-sized thinking around the marketing of seafood products in America. The result will be that people will want to eat more seafood both from our wild habitats and most importantly, from our water farmers. We have incredible solutions to offer to save this planet and we're not taking advantage of them.

Have you mainly source wild or farmed seafood in the past?

I remember working in a restaurant 22 years ago. I'm trying to order fish from my supplier in Maine and everything was so expensive. By the time we got it shipped here, I couldn't serve it in my restaurant in Minneapolis. People didn't eat that much seafood here. I put a raw bar in my restaurant – it was the first one people had seen! They were like, “What are you doing?” There we were, shucking clams and oysters.

I remember my supplier, from Brown Trading Company, telling me, “Well, we have this other thing. Are you familiar with wolfish?” And I'm like, “Sure, loup de mer?” This was a very specific wild Northern Atlantic fish. It was $3 a pound! Within three years, this same fish was over the $17 mark. We could no longer afford it! At the same time, 25 years ago, aquaculture was a confusing topic for chefs like myself. Fish farming practises didn't line up with some of the moral equations that chefs like myself were wrestling with.

My evolution began shortly thereafter.

What was the moment that helped you to appreciate sustainable aquaculture?

I kept investigating fish and fish stories. There was so much opportunity for growth in the aquaculture business. I think it was President Clinton's administration that started to subsidise tobacco farmers to help them get out of tobacco. All of a sudden there was a surge in aquaculture production in the South. Then I started doing TV and travelling to Asia. I saw mangrove forests in coastal Vietnam and Thailand. I started to see fish farming of sturgeon in central Taiwan and in the People's Republic of China. Someone turned to me and said, “Yes, our family has been doing this for 5,000 years.”

It wasn’t long after that when I went to Hawaii, where indigenous people told me that the king would have runners that would carry live fish from the ocean in a cloth that was soaked in seawater and wrapped in leaves. They had to run the fish as fast as they could before it died, or they would be beheaded. They put the live fish into buckets of seawater to have “fresh fish” close by. After many years, they figured out that they could use that ancient wisdom and apply it to raising fish in ponds and mountain streams. It was then that I realised this isn't a modern thing. This is ancient wisdom, and I should listen.

Is there a particular farm or farmer that helped you change your opinion?

It was probably about ten years ago. I was on a trout farm in Pennsylvania. I did not want to taste their fish because farmed trout was probably the biggest example of poorly farmed fish, in my mind. Some of the worst farmed fish I have ever tasted was trout. I really wasn't looking forward to it. But here were these two young guys, eager for me to see this, with a system that was less than, shall we say, sophisticated. They were on a swift part of a river outside of Pittsburgh. They had fast-moving water, they were raising these trout, and they were trying to figure out how to sell it. They had 500 fish swimming in this raceway, if that!

Next, they tell me that they want to pull out a trout and grill it for me! I am thinking, how am I going to politely tell these guys, “better luck next time”? But then, I ate their trout. I was like, ok, I'm being punked. This is wild fish. But sure enough, it was a stunning farmed trout. From that point on, my eyes were opened.

© The Travel Channel

How do you see aquaculture evolving?

There are so many good things happening in aquaculture. Once I tried a fish called Verlasso salmon I sort of dug into the industry and started tasting farmed sturgeon, farmed trout, farmed bass, farmed cobia. The future of our well-being in this country is to think of ourselves as part of a global system, a global economy, a global everything – especially now that our climate crisis is so real. We have to come at aquaculture from the same viewpoint. Increase global understanding. Make it the basis on which we are going to repair our problems. Use better technology. Farm chemical- and antibiotic-free. Do not overcrowd the pens or farm in areas that should not be farmed. We can do this, but we have to do it in the right way.

What are the three most crucial issues facing people and the planet?

The biggest one by far is climate change. I think everything starts with addressing that. I'm extremely frustrated when companies announce that “because of climate change,

in 20 years we are going to…” To say it's pissing into the wind is an understatement.

We need an immediate global, systemic halt to doing harm to our environment. I am stunned at the foot-dragging globally. Does it mean that some businesses, through the power of law, will literally be told, “You cannot be in that business anymore”? Yeah, that's what's going to have to happen.

I ask, “Is this the planet we want our planet to be? The time to act is now, before our domestic population areas are uninhabitable. We have, over the last couple of years, seen the first climate refugees in the world. We simply cannot continue to go down this road. Farmers are jumping up and down about these issues, trying to say, look at me, look at our climate issues. At the root, we have a massive failure of leadership in America at the federal level, where science has been discounted and the people who are losing are all of us. It's an economic disaster for farmers.

On top of that, visas have been limited and restricted to the point where there are not enough people to do this important work. That brings me to the second issue. We need leadership on immigration. Migrant workers, documented and undocumented, feed our country. Full stop. If we don't settle that issue and allow for those folks to come in and help us do our work, we will not be able to solve the critical issues around food.

They pay taxes on their paychecks, they support the economy, AND their money that goes back home to their countries of origin helps keep those communities stable. So it's not only a jobs and economic development issue in our country, but it's a national security issue overseas. Friends will ask me, “Did you see there's gun violence at a bordertown in Mexico?” To which I answer: “If people had jobs there and people were spending money, opening businesses, that’s the kind of thing that stabilises a community.”

The final issue that must be solved is health and wellness. We have to eat our way into a better world – less protein, more fruits and vegetables, more seafood, more beans and pharyngitis foods. We are addicted to salt, sugar, and fat. We are the middle of the supermarket. As far as I'm concerned, convenience foods can be remade into healthy and nutritious foods. If we do not do that, if we do not allow for everyone to have the ability to shop for healthy, nutritious food, then the cost alone for healthcare will be catastrophic for our economy.

We have to get leadership to accelerate our timetable on climate, immigration, and health and wellness issues. Solving these issues is critical to our people and our planet.