Originally built in 1974 it was totally rebuilt in the early years of this century.

It was as a young engineering graduate that Dick Haldane first heard about fish farming. Having spent much of his boyhood catching trout in his native Perthshire, he was inspired to visit a friend who was working at Gateway West – a trout farm in Argyll that had recently been established by Shell.

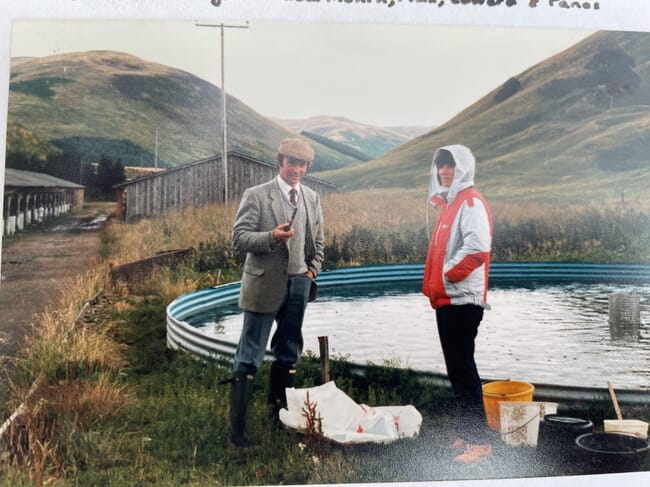

“It was then that I met Kris Dalsgaard, who was the fishmeister. I said I had a little bit of water and was fascinated by the idea of fish farming,” Haldane explains.

Dalsgaard, who had learned his trade in Denmark’s world-leading trout sector, soon came to visit Haldane’s family farm to look for potential locations. Despite the comparative paucity of water available he decided that a farm – of sorts – could be established at a place called Nether Cloan.

Behind him, under fairly rudimentary cover, are 68, 12 ft. diameter tanks.

“’As there is very little water, what we’ll do is we’ll grow lots of little fish, not any big fish’, Kris suggested. So, in August 1972 we almost immediately formed a partnership, built a house for Kris and by early summer 1974 we had our first 4.5 g fingerlings ready for market,” Haldane recalls.

The success of the first farm inspired Haldane and Dalsgaard to set up two more, in 1974 and 1975, at nearby Frandy and St Mungo’s. The former lay immediately below two, 200 acre Waterboard reservoirs, with a guaranteed compensation flow as its water supply; the latter was fed by St Mungo’s Well, a reliable spring. Both were successfully developed by Dalsgaard, and Frandy soon became the biggest trout fingerling farm in Europe.

“In ’74 we sold 700,000 [4.5 g fingerlings], in ’75 we sold 1.8 million, and in ’76 we sold 3.4 million, so it was a very quick expansion – the reason being that there were no other trout farms in the country specialising in fingerling production. The only other fingerlings available were the leftovers from mostly relatively small-scale farmers who were producing a few trout for the ‘table market’ and for their local rivers,” Haldane explains.

“The other key was that you couldn’t import live fish from abroad, which was another reason that the industry was just waiting to expand. Without any market research – and therefore clearly by chance – we suddenly started producing fingerlings at the right time. Without our fish the market couldn’t have expanded, but I take no credit for that at all. If we had had enough water we would probably have followed the sheep and grown a small number of table-sized fish,” he adds.

Cloan’s fingerlings were sold for on-growing by the relatively new and much larger producers in the south of England – such as Kimbridge, Trafalgar and Test Valley Trout – for the then booming table trout market. But, despite the sales growth, margins were tight.

“Even though we were selling 3 to 5 million trout a year we didn’t make much money, as they didn’t sell for very much,” Haldane recalls

It was also brutally labour intensive, with all grading – which needed to be done three times per cycle – done by hand. But, despite the challenges, Haldane continued and further expanded his operations in 1986, buying Westmill. Originally designed by Dalsgaard, to supply Scotland’s expanding table market, Haldane soon turned it into Scotland’s largest flow-through farm by adding the extraction and discharge licences for the defunct Eastmill farm. This doubled both his water supply and carrying capacity and he went on to diversify Westmill into producing medium-sized fish for on-growing too.

“In our first year we transferred 5 million 5 g fingerlings from Frandy to Westmill and sold them as larger grown-ons of 20-100 g, which would be able to survive challenges from conditions such as prolific kidney disease (PKD), which was rife in places like Hampshire by then,” he explains.

The dual model worked and, by the turn of the millennium, Westmill’s production had risen from 40 tonnes to over 300 tonnes – split evenly between grow-ons and restocking fish.

Forays into salmon and char

While rainbow trout have always been the mainstay of Cloan’s business, in the late 1980s Haldane, Chris Saunders-Davies of Test Valley Trout and another friend of his, went into partnership and established a salmon hatchery at Templeton, near Kinross, and at Fossoway, roughly 8 miles downstream of Frandy. They also set up a salmon farming company, Mull Salmon – which some years later they sold for a pittance at a time the salmon sector was at its most fragile.

Under his Cloan Hatcheries umbrella, he also diversified into Arctic char. Reflecting on this today, he remains surprised that the latter didn’t gain more traction, given the appetite for the fish in other countries and their natural suitability for intensive production.

“They are – in theory – very valuable: if you go to a restaurant in central France, ‘Hombre Chevalier’ are the most expensive item on the menu. Char also love to shoal – the tighter you pack them the better they grow. They don’t seem to fight. We were staggered by the stocking densities we were keeping them at. But we couldn’t sell them,” Haldane recalls.

“We desperately tried to get them into the fish market in Glasgow but didn’t have enough to ensure continuity. I still don’t quite see why nobody in the trout game has gone for them,” he wonders.

“Perhaps my less than rudimentary knowledge of marketing was my real problem. After all, in all my years of growing baby trout – sales by now approaching 100 million fish – I had never advertised or even phoned anybody in an effort to sell them. The farming fraternity seemed to know who we were, and where to find us – and they came to us. I appreciate that may sound immodest, but it’s how it was,” Haldane explains.

Changing tastes

One of the defining features of trout farming since the turn of the millennium has been the move from portion-sized trout to ones that are large enough to fillet – an era heralded by the arrival of Dawnfresh, a company that began farming trout in Loch Etive (which is a sea loch) in 2006 and grew to four sites on the loch.

“The market quickly moved from portion-sized trout to fillet-sized trout of 3-4 kilos. I’m amazed that growing large trout on a large scale didn’t take place sooner. I suppose the obvious answer was the lack of available fresh water supplies. When it was shown that, once grown to a suitable size, trout adapted readily to a salt water environment – at one time a seemingly limitless supply of which surrounds the UK, they could follow their perceived-to-be-nobler cousins – and have now gone down the salmon route,” Haldane reflects.

“What this, of course, did was to cut the demand for fingerlings by a factor of ten. At our peak, annual production at Frandy was 10 million 5 g trout. It now produces half a million 100 g fish,” he explains.

Dawnfresh became one of Haldane's key customers

Haldane not only supplied companies such as Dawnfresh directly with special salt-acclimatised fry but also leased them three of his sites – Frandy, St Mungo’s and Templeton – which provided the juvenile fish for their marine farms.

Looking ahead

The future of Scotland’s trout farming sector is far from secure, following Dawnfresh – the UK’s largest trout producer – going into administration earlier this year.

“The jury is out over what’s going to happen in the next few months with the sale of Dawnfresh. My guess is that, as salmon farmers have very deep pockets, they will get it if they want it,” Haldane ventures.

Other issues include the increased incidence of dry spells – which mean a more regular need for trout farmers to aerate their ponds – and the falling popularity of angling, and therefore the contraction of the restocking market.

Dick’s elder son Adrian, aged 12 at the time, later spent a couple of years working at both Westmill and Frandy, before deciding that fish farming was not for him.

“Fishing is becoming an old man’s game,” Haldane reflects. “So we’ll be converting more and more back to producing grown-ons rather than restocking.”

Abiding memories

Looking back over the last 50 years Haldane reflects that “the big financial success came from buying Westmill, because it gave us a quantum leap in turnover – from £250,000 to over £1 million very quickly.”

“The very early days were also, I suppose, a success. My father told me to forget about being a trout farmer as quickly as I’d thought of it, but after he saw the breakthrough of the fingerling farm he soon became even more enthusiastic than I was. But I still maintain this was luck – it wasn’t me being particularly clever,” he reflects.

Outside of farming he speaks with great enthusiasm of long distance running – and, in particular, of a 15 week, eight time-zone 11,000 km relay race from Vladivostok to St Petersburg which he organised in 2005 to raise money for Russian orphanages. Having himself completed nearly 600 km of the run, he flew down to Moscow, stopping off to run its annual marathon on his way home.

Not only did it raise nearly £1 million and earn him an MBE, (ordinary Member of the extraordinary order of the British Empire), but it was also praised by the – then relatively new – Russian president, Vladimir Putin. The framed telegram from the Kremlin may no longer hang in pride of place.

Unfortunately, the trout sector hasn’t managed to mirror the meteoric rise of the salmon sector in the time Haldane’s been farming. However, he sees this as being largely inevitable – due in part to the limited availability of fresh water; in part to the comparatively modest standing of trout compared to salmon in the eyes of the consumer; and in part due to the fairly consistently high profit margins of the salmon sector.

“It’s one of the reasons we went into salmon farming in 1987, and did it for eight or nine years but we came out at just the wrong moment and sold the company, my share being 7p,” he chuckles.

While the fate of the trout sector might be in the balance Haldane believes there’s still scope for growth.

“There’s no doubt there’s a future for companies such as Kames and Dawnfresh. And if there’s a future for them then there’s a future for us,” he asserts.

However, whether the next phase occurs under Haldane’s continued supervision remains to be seen, and he points to the fact that he’s not getting any younger.

Indeed, back in 2008, when Cloan first let all four of its farms and hatcheries to Dawnfresh, Haldane assumed he had effectively retired from fish farming. And, being relatively youthful and fit he immediately launched out on a totally new occupation, the breeding of pedigree Highland cattle. With no employees and only occasional help from local farmers, he and his wife Jenny, the latter only 18 months his junior, now have a fold of over 50 beasts, with its annual crop of 20-plus calves expected in March and April next year.

So, now in his 76th year, Haldane is not exactly idle. And – as he finds his Highlanders rather more loveable than his trout – he might not be averse to an offer for Cloan, or handing over to someone who wants to take a significant stake in the business.