FAIRR's 2022 Oceans and Biodiversity Impact Report expresses concerns that even fisheries which are certified for managing their target stocks well, might have wider biodiversity impacts that are not taken into account by the certification bodies.

This article is the first installment of a three-part series which presents the main findings and trends that emerged from the Oceans and Biodiversity Impact Phase 2 report.

The main focus is on the fact that, while the aquaculture industry and aquafeed producers have shown an admirable commitment to reducing their greenhouse gas emissions, they also need to address their impacts on biodiversity – both on land and at sea.

Trends in feed ingredient sourcing

In 2022 the FAIRR initiative engaged eight of the world’s largest salmon producers on their respective feed strategies and approach to the range of biodiversity and climate risks that aquaculture feed ingredients pose.

The meetings underlined that aquaculture companies are keenly focused on reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. However, they are not focused on looking holistically at their ESG risks and using a nature-based approach.

A close examination of these companies’ carbon reporting shows emission-reduction efforts largely sit within Scopes 1 and 2 – ie relating to direct and energy-related emissions – via projects such as the electrification of feed barges and switching to renewable energy in processing facilities. Yet Scopes 1 and 2 emissions typically account for less than 40 percent of company emissions, with the remainder sitting in Scope 3 – primarily through feed sourcing and the transport of finished products. This inconsistent approach risks undermining the companies’ and investors’ efforts to reach emission reduction targets.

Five of the eight companies stated that GHG emissions are a top priority, with four having verified targets under the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi). Despite this, when asked about the risks arising from producing and sourcing feed, none of the companies presented a nature-based approach to reducing both their GHG emissions and biodiversity footprint.

The focus on reducing the emissions associated with feed is exhibited through the trade-off between the inclusion of fishmeal and oil (FMFO) and soy protein in salmon feed. Soy protein, the majority of which is sourced in Latin America, has a high emissions footprint relating to the deforestation often associated with its production. FMFO, however, boasts a lower carbon footprint, based on current estimates

However, evaluating feed ingredients on their emissions fails to address the inherent biodiversity-related risks associated with the sourcing of FMFO. Forage fish, from which FMFO is sourced, play an essential role in preserving ocean health. Damage to their populations can cascade across trophic levels and impact other high-value fish stocks, such as tuna, as well as endangered and protected species. Furthermore, 21 percent (2.1 million tonnes) of the total catch for FMFO purposes comes from poorly managed fisheries.

Companies readily cited certification of marine ingredients as a silver bullet, removing biodiversity risk from their feed, however, this reasoning is not shared by the certification bodies themselves, as these organisations make no claims that certification limits biodiversity impacts, only management of specific stocks. Although certification is a useful tool to increase investors’ confidence, the standards in which it is rooted do not necessarily cover every aspect of the biodiversity impacts associated with fishing methods such as trawling, dredging and lost gear.

The catch method utilised needs to be considered when assessing the risk of these ingredients as it is often a determining factor for the biodiversity impact of fishing due to the damage it can pose to marine communities and habitats. There is also an urgent need to quantify the potential emissions that arise from sediment disturbances related to fishing activity and catch method with the UK’s Climate Change Committee (CCC) stating that this may impact emissions, potentially undermining current carbon accounting as scientific understanding increases.

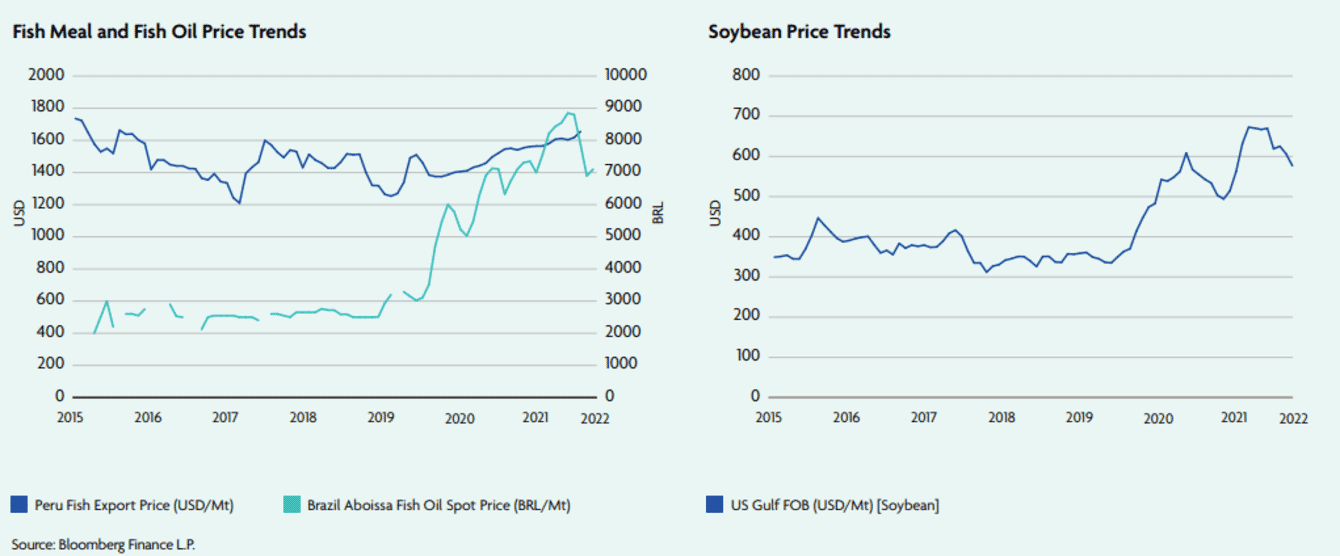

The dramatic rise in soy prices has encouraged feed millers to look more towards fishmeal © Bloomberg Finance

Another dimension to the emissions-biodiversity trade-off that has been playing out is the increase in soy prices in recent months, whilst fishmeal prices have stayed reasonably flat (see graphs above). This incentivises feed millers to move from soy to fishmeal, shifting the ecological burden offshore and into our oceans. With the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD)* expected to unveil its framework for risk management and disclosure in late 2023, this trade-off is already of huge significance, with organisations being required to disclose both how nature impacts them and how they impact nature.

Companies need to take a holistic view of the risks and impacts which their choice of feed ingredients poses. Whilst focusing on reducing emissions has its benefits, it does not address the issues of biodiversity impacts, a fundamental component in preserving the long-term productivity of the marine systems which these companies heavily rely upon.

*As the nature equivalent to the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the TNFD is set to enhance the disclosure of nature-related risks for investors, thus marking an important step to incorporate nature-related risks in financial decision-making, which has already been endorsed by the G7 and the G20. The TNFD is also expected to integrate the concept of "double materiality" more into its work than the TCFD as organisations will disclose how nature is impacting them, and how organisations impact nature.