© Matt Moretti

Operating off a commercial dock in downtown Portland, Maine, Bangs Island Mussels boats are a familiar sight in the New England harbour city. Harvesting mussels year-round and kelp in the wintertime, the family-run company just announced they are branching into yet another income stream: oysters.

“We are now stewarding Chebeague Island Oysters and getting our hands dirty with another impressive bivalve,” announced Bangs Island Mussels on their Instagram this November. Grown in inter-tidal bottom cages, Chebeague Island Oysters are also produced in Casco Bay, near their mussel farms. The company said it was happy to be branching out into another “filter-feeding, environment-improving” shellfish.

“We basically grew up side by side in Casco Bay,” says Matt Moretti, CEO of Bangs Island Mussels. “The idea was to capitalise on the efficiencies that we've already created for mussels - like having a distribution network. We have customers across the country.”

Now, their oysters will piggyback on the same shipping infrastructure and will be distributed in markets including Illinois, Colorado, Georgia, Ohio, New York, Louisiana and Washington, DC.

“We started mussel farming because it was the most sustainable form of food production we had ever seen,” says Moretti, who believes that mussels should be a much larger part of the American diet. “It has the potential to do so much good [and] produce so much highly nutritious food with such a small impact on the environment.”

The Moretti family operates the largest rope grown mussel farm on the East Coast of the United States, with a team of 13 full-time crew working across nine sites on 32 acres, harvesting around 270 tonnes of mussels a year from the clean waters of Casco Bay.

But when they started in 2010, it was a risky business, as many Americans were unfamiliar with live mussels. Mussels were much more popular in European countries like France or Belgium, where the per capita mussel consumption is around 2 kg - 4 kg a year.

However, according to a 2022 report by Gulf of Maine Research Institute, the market for live mussels is growing at a rate of 4 percent a year in the US, something that Moretti sees in his business.

“The American diet is changing… people didn’t used to eat mussels unless they were hyper-local to the coast,” explains Moretti. Now Bangs Island ships their shellfish as far as Colorado, thousands of miles from Maine.

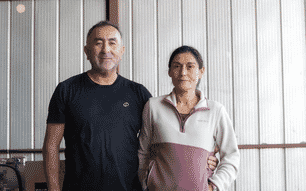

Following the purchase of a neighbouring farm, the Moretti family now produce oysters alongside kelp and mussels © Matt Moretti

In addition to oysters and mussels, Bangs Island farms kelp, but they’ve found that It is easier to wholesale seaweed then sell directly to consumers. Moretti laughs, remembering a kelp jerky product that they initially manufactured but never took off in sales.

“Kelp is a little tricky on the farm side - the market is still developing,” said Moretti. He often gets asked by newer aquaculture enthusiasts interested in farming seaweed and he says, “it's very important that you have a market or a way to sell it… before you start growing.”

Luckily in Portland, Maine - the heart of America’s kelp industry - it was easy to find someone to buy their wholesale kelp. Now, Bangs Island sells about 45 tonnes of raw kelp every year to Atlantic Sea Farms, a popular US kelp food company. With retail items like Sea-Chi, a kelp-based kimchi, or their Sea-Veggie Burgers, Atlantic Sea Farms has four products in every Whole Foods outlet in the US and distributes in national supermarket chains like Sprouts and Albertsons.

Growing commercial-grade kelp at scale has led Moretti to achieving one of his early dreams: setting up an integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) farm, where species from different trophic levels are grown in proximity to each other. He devotes two sites to co-culturing mussels and kelp, and tracks the data from the farm in a partnership with Bigelow Ocean Science Laboratory and the Island Institute.

© Shutterstock

The world-class research institutions became interested in studying IMTA when they realised that the Gulf of Maine is warming 99 percent faster than any other body of water on the planet. As a result, it could become too acidic for juvenile bivalves - like oyster or mussels - to form shells as early as 2030. This news was frightening to the local aquaculture, fishing and lobstering community in Maine which makes up a large portion of that state’s revenues; the seafood sector brought in $611 million in 2023.

Startled by these findings, Dr Nichole Price and Dr Susie Arnold, of Bigelow Ocean Laboratory and the Island Institute began working with Bangs Island Mussels in 2016 to study how co-raising species like seaweed and shellfish could help fight ocean acidification.

“We wanted to understand if kelp could remove enough carbon dioxide from the water, the major cause of ocean acidification, to improve water chemistry in and around the farm,” said Dr Arnold, in a 2021 post about the study.

The scientists found that raising shellfish near seaweed does decrease acidification locally and has led to thicker mussel shells, calling the phenomena the “halo effect.” These studies are still preliminary but Moretti says working with world-class researchers has been “validating.”

Co-raising shellfish and seaweed “is one of our climate change mitigation strategies that is all natural,” says Moretti, who was initially attracted to raising kelp and shellfish for their positive impact in the water.

“All those individual species on their own have the potential and do help the environment around them as they're growing,” says Moretti. “If you put them together, the hope is that they can also help each other grow better and potentially have an even bigger positive impact on the environment around them.”