Shellfish are struggling to thrive as ocean water becomes more acidic © Kelp Blue

One of the most serious climate change-related threats to shellfish is caused by increasing levels of carbon dioxide (CO₂) in the Earth’s atmosphere. As CO₂ makes its way into the oceans, chemical reactions occur that lower pH and create ocean acidification. For the past two decades, climate change research has shown that rising CO₂ levels in surface waters threaten shellfish that require higher-pH waters to grow and survive — an alarming discovery in coastal zones where additional sources of acidity can further reduce pH and slow certain species’ shell formation.

But researchers may have learned that kelp could help ameliorate this phenomenon.

A Stony Brook University-led study titled “Kelp (Saccharina latissima) mitigates coastal ocean acidification and increases the growth of North Atlantic bivalves in lab experiments and on an oyster farm,” reveals that harvesting kelp may be a new way to help keep bivalves such as clams and oysters healthy and more abundant. The study, led by Christopher Gobler, endowed chair of coastal ecology and conservation at Stony Brook’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS), and colleagues was published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

Mike Doall and oyster farmer Paul McCormick with kelp grown on the Great Gun oyster farm © Christopher Gobler

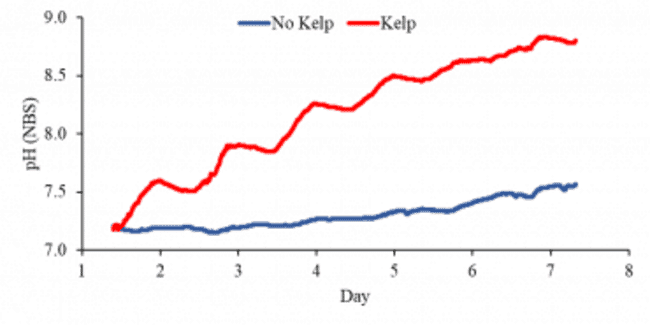

Gobler and his team conducted six experiments to assess the effects of elevated CO₂ and the presence of kelp on the growth rates of three different bivalve species: Eastern oysters, blue mussels and hard clams. In each of the experiments, kelp cultivation significantly reduced acidification. The research was supplemented with a field experiment at Great Gun Oysters aquaculture farm in East Moriches, New York.

“When people think about climate change, they’re most apt to think the weather is getting warmer, temperature is getting hotter, and that there are more heat waves, but a less well-known symptom of climate change has to do with our oceans,” said Gobler.

The study demonstrated that the deployment of kelp on an oyster farm combats ocean acidification and therefore helps protect bivalves. The process may also have additional ecosystem and aquaculture benefits, including the sequestration and extraction of carbon and nitrogen, and protection against harmful algae blooms. Gobler said acidification is detrimental to coral reefs and different types of algae, as well as species that need calcium carbonate to make their shells, including bivalves.

“This also affects lobsters and crabs,” said Gobler. “Making shells becomes more and more difficult as the levels of CO₂ increase in our atmosphere and in our oceans.”

The research team found that during a one-month deployment, oysters that were surrounded by kelp enjoyed higher-pH water and grew significantly faster than individual shellfish located farther away where the pH of the water was lower.

Mike Doall, associate director for bivalve restoration at SoMAS and a member of the research team, said kelp can be a beneficial and profitable option for oyster farmers.

“I’m an oyster farmer and I started thinking about kelp 10 years ago when I was looking for ways to diversify my business,” said Doall. “I met somebody who was growing kelp in Maine and my first reaction was one of surprise. I had no idea why they were growing it or what they were going to do with it. But the more I looked into it and the more I researched it, I began to realise that this is the perfect companion product of oysters.”

pH scale measurements with and without kelp. The graph shows continuous pH (NBS scale) bubbling, and the addition of 4 x 104 cells mL-1 Isochrysis galbana added daily to simulate daily feedings of bivalves © Christopher Gobler

Doall explained that kelp has an opposite growing season from oysters. Specifically, farmers can divert resources from oysters in the warm months to kelp in the colder months. What’s more, kelp can be integrated vertically with oysters and other shellfish, which means that farmers can diversify without having to replace one crop for another out in the ocean.

Overall, the research clearly shows that the cultivation of kelp constitutes an environmentally friendly means of protecting shellfisheries against present and future ocean acidification and other coastal stressors.

“We’ve helped grow kelp on 10 oyster farms across New York since 2018, and more and more aquaculturists have been hoping to incorporate kelp into their farms,” said Doall. “In addition to providing crop diversification and additive revenue streams, the ability of kelp to fight ocean acidification gives these oyster farmers one more reason to add kelp as a second crop.”

Doall described kelp and seaweeds as, “unlike anything else you can grow on land and water.”

“There are zero inputs,” he said. “You don’t have to fertilise them. You don’t have to feed them. They don’t require pesticides or insecticides. They suck up carbon dioxide, and they also suck up nitrogen, which is one of the major water-quality problems facing Long Island and other coastal areas. The result is a net extraction from the environment. So there are a lot of really good environmental and economic reasons to grow kelp.”

The recent study builds on previous research by the same SoMAS group demonstrating that kelp has the ability to deter the intensity of harmful algal blooms, another environmental threat to shellfish aquaculture. That study was published in the journal Harmful Algae in 2021.

Both Gobler and Doall said the findings could have powerful implications for oyster farming in coastal zones on Long Island and around the world.

Researchers at Stony Brook have also demonstrated that kelp can deter the intensity of harmful algal blooms, another environmental threat to shellfish aquaculture

“We have been witnessing coastal ocean acidification for years and have documented its ability to slow the growth of, and even kill off, shellfish,” said Gobler. “We began growing kelp on oyster farms to simply expand aquaculture regionally. After seeing its ability to rapidly take up CO₂ and improve low pH conditions, we knew it had the potential to benefit shellfish experiencing acidification. And while showing that in the lab was exciting, being able to improve the growth of oysters on an oyster farm experiencing coastal acidification proves this approach can have very broad applications.”