The Asian shrimp sector may face its biggest challenge since the outbreak of early mortality syndrome (EMS), which took place in 2011

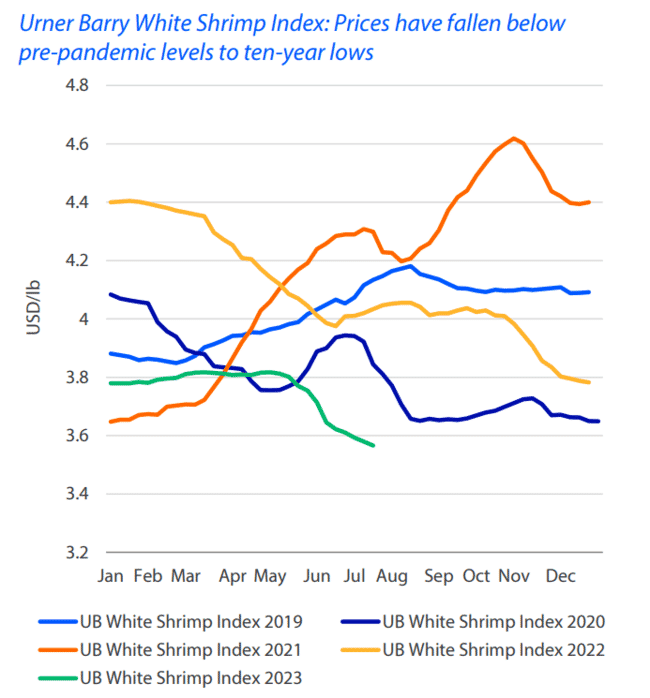

So forecasts Rabobank in its H2 outlook, which was published today. The new report suggests that continued low prices for shrimp, combined with a reduction in the availability of fishmeal, due to an El Niño-related slump in forage fish landings, is going to make margins extremely tight right across the aquaculture value chain, with shrimp farmers likely to be hit the hardest.

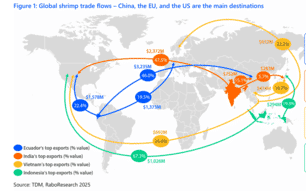

As the report notes, shrimp demand in the US and Europe has experienced a sharp drop in the last six months, due to inflation and economic recessions. Meanwhile, in China – where it was predicted to soar, following the more recent removal of lockdown restrictions – it hasn’t rebounded as much as anticipated, leaving suppliers stuck with stockpiled inventory.

And Rabobank predicts that prices are likely to fall even lower, due to a further drop in demand from China, combined with the continued growth of Ecuador’s production, and the report suggests that the Asian shrimp sector could be facing its most challenging period since the initial outbreak of early mortality syndrome (EMS) hit the region in 2011.

In Asia, according to the report, “virtually the entire industry is operating at a loss per kilogram sold”.

The green line plots 2023's prices in US dollars per pound © Urner Barry, Rabobank

“It’s the worst year since 2020 due to the drop in demand. China propped up the world at the end of 2022 and Q1 of 2023, as 2023 rolled out it turned out the Chinese were spending less than predicted. The economy is not opening out as fast as we thought it would and they’re experiencing deflation,” the report’s lead author, Gorjan Nikolik, explains.

To add insult to injury, retailers have been slow to respond to the softening demand.

“What’s really concerning is that retail pieces have stayed flat, which is preventing a demand recovery in Europe and North America,” notes Nikolik.

The result is that producers – especially in Asia – are heavily reducing their investments in broodstock and post-larvae.

“Indonesia, which targets the US market, has already cut production by 20 percent in H1; Vietnam – selling to Europe and the US – cut production by 20-30 percent; India hasn’t reduced production – it seems they didn’t get the message on time, but now broodstock imports have fallen by 40 percent – which could mean a collapse in India’s shrimp production in H2,” notes Nikolik.

The continued growth of Ecuadorian production – which rose by 19 percent year-on-year during H1 – is compounding the softening of farmgate prices for shrimp across the world.

“Ecuador created most of the oversupply: as they didn’t experience the slump in H1, as 70 percent of their stock goes to China, they are still growing. Finally they are reducing their growth rate, from 25 percent to 12 percent, but it’s still growth and Ecuador will probably record a 12-15 percent growth rate for this year over last year. The nightmare scenario [for Asian producers] is that Ecuador will start targeting the European and US markets, instead of relying China,” Nikolik warns.

There is, however, a possibility that things might improve – but not until 2024, according to Nikolik.

“Ecuadorian producers are seeing the price collapse and realising they cannot pump more volume into the market. If retailers drop their price sand Ecuador and India produce less it could improve things, but it’s going to be tough and most of the sector will lose money,” he explains.

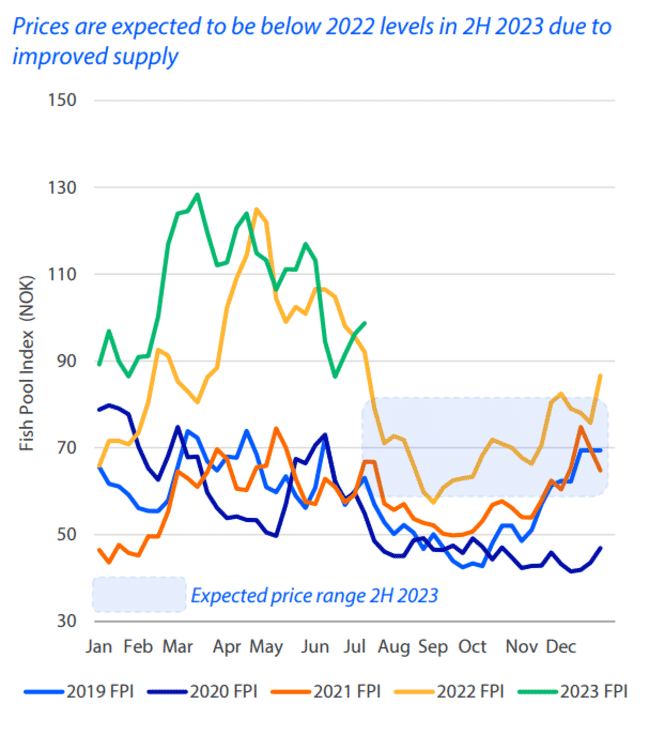

Salmon stay strong

Meanwhile, the outlook for the salmon sector, following six months of excellent prices in H1, is looking much more optimistic.

“Norway’s salmon sector has had one of the most profitable periods in its history. Although there has since been a correction in salmon prices, they are still high compared to historic levels – due in part to the contraction in the sector. Salmon farming in Norway – as well as in Scotland, Faroes and Iceland – is the most profitable part of the whole global aquaculture industry at the moment,” Nikolik explains.

However, as the report points out, in Norway, 25 percent of these profits will be going to the government’s resource rent tax programme, which was passed last month but retroactively enacted from 1 January. As the report notes, this will mean that 47 percent of salmon farming companies’ profits will be lost to tax. However, whether this will impact land-based, offshore or closed-containment systems hasn’t been made clear yet. Moreover, the opposition parties have promised to revoke the tax, should they come to power in the 2025 elections, the report adds.

The shaded area marks the projected price for H2 2023 © Fish Pool, Kontali, Rabobank

The impacts of El Niño

The advent of a strong El Niño , which has meant that the Peruvian anchoveta fishing season has been cancelled, has created a great deal of concern about the shortage of – and therefore the increased price of – fishmeal.

This year’s supply of fishmeal is going to be down by over 500,000 tonnes and the price for Peruvian fishmeal is now $2000 per tonne and is likely to go higher soon, according to Nikolik. And, following fish oil shortage and price spike to $5500 per tonne, in H1 2023 up from $1800 in H1 2021 – it could really give some impetus to the companies developing alternative aquafeed ingredients, such as insect meal, single cell proteins and algal oils.

“It gives more urgency to all those people scaling up – the sector really needs it,” Nikolik reflects.

However, he adds that exactly how El Niño will impact aquafeed supplies in the coming year or two is the subject of speculation.

“We can’t predict the future but we can look at the last time it happened – in 2014 – which was one of four mega El Niños that have happened since 1990,” says Nikolik.

“What happened afterwards was interesting. 30-60 percent of the Peruvian anchoveta biomass is harvested most years. But, when you don’t catch the fish, for the next season they grow and, in 2014, this led to a very large biomass in the subsequent season and a 2.5 million tonne quota of which 97 percent was caught. It seems likely something similar will occur this time,” he explains.

Nikolik also notes that El Niño could have some benefits in terms of production of other key feed commodities.

“On a more positive note, soy prices are falling; Brazil is due to have a record crop; there’s less demand in China; so overall costs of some aquafeeds might be similar,” he points out.

However, as Nikolik observes, some species and regions will be hit harder than others – depending on whether the suppliers are able to formulate feeds with lower fishmeal content, with those in Asia perhaps finding it harder to adapt. And there may be other impacts of El Niño.

“El Niño can also increase the risk of flooding in Ecuador, which could totally change the global supply. Meanwhile, in Chile, there’s a risk of more algal blooms affecting the salmon sector. These may or may not materialse, but still add to the difficulty of the year,” he notes.

“After two very good years it is going to be a very challenging few months – and it might get worse before it gets better,” Nikolik concludes.