The reopening of China's food service sector has sparked a dramatic increase in seafood imports.

So explains Gorjan Nikolik, Rabobank’s senior seafood analyst. He’s been tracking global seafood trades for almost two decades and sees the new statistics as heralding one of the most significant shifts that he’s covered to date. One that has a wide range of causes and implications, which go beyond the seafood world.

Short-term drivers of import growth

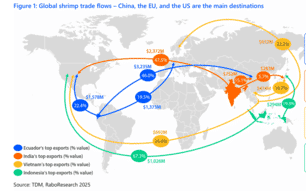

According to Nikolik, a large part of last year’s increase in seafood imports to China were accounted for by shrimp – with the bulk of these coming from Ecuador (564,597 tonnes) and India (136,838 tonnes). This was a reflection of the opening up of the food service sector – a sector that had been crippled by Covid-19 restrictions and concerns since the start of the outbreak.

However, the relaxation of rules that occurred in 2022 – alongside government indications that the first proper celebration of Chinese New Year since the pandemic began would be permitted – meant that many importers filled their inventories in preparation of a bonanza.

“For two years seafood demand has been very suppressed and the importers expected that people were eager to celebrate this year,” he explains.

While it's too early for Nikolik to have access to the figures, anecdotal evidence suggests that Chinese people are heading back to restaurants in increasing numbers, paving the way for a year of strong seafood demand, after two quiet years, and he expects China’s that status as a net seafood importer is here to stay.

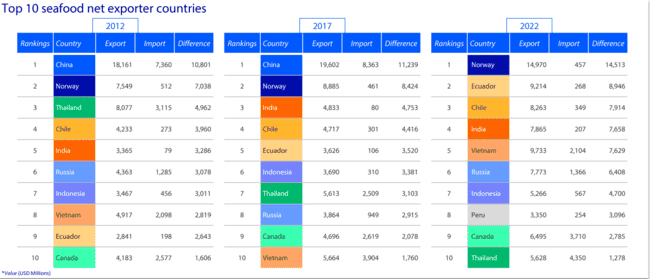

2022 marks the first time that China has become a net seafood importer, following a 30 percent growth in imports. © Rabobank

Longer-term trends behind import growth

At the other end of the price scale from shrimp, Nikolik was surprised to see a huge upsurge in imports of pangasius fillets from Vietnam – with the year-on-year figures increasing by 109 percent by volume (and 147 percent by value) in the first half of 2022. It’s an uptick that has been welcomed by Vietnam’s pangasius sector, as well as one that might also suggest a change in the habits of Chinese consumers.

“It’s quite surprising because China is a huge producer – and exporter – of freshwater white fish and is the world’s largest tilapia exporter, yet ended up importing a large volume of pangasius. This suggests pangasius has an edge and might be a reflection of the growing demand for convenience seafood products among the younger, urban generation, who don’t have time to cook traditional seafood meals,” he reflects.

“It’s interesting: both because China is the biggest producer of tilapia and because we always assumed that they didn’t really have an appetite for fillets, but they bought more pangasius in 2022 than the US and Europe combined,” he adds.

Meanwhile, longer-term trends that are helping to drive seafood imports include, according to Nikolik, the country’s ageing – and increasingly affluent – population. Not least as this is a dynamic that is leading people away from fish farming and wild catch and into other sectors.

Nikolik believes that China is rethinking their old policy on being self-sufficient in seafood and is no longer determined to be a large net seafood exporter. © Chen WS

“This means that – across the economy – they are producing less domestically but consuming much more. In such situations there’s a tendency to shift towards producing higher value products, so there’s been a shift away from the production of fish, towards the production of things like batteries or electric cars – things with high value and high export potential, which is where the government will focus. It seems like they’re loosening up their old policy to be self-sufficient in seafood and are no longer determined to be a large net seafood exporter. It’s a natural progression for the economy,” he explains.

Other factors influencing China’s declining focus on domestic seafood production include the decommissioning of much of the country’s long distance fishing fleet.

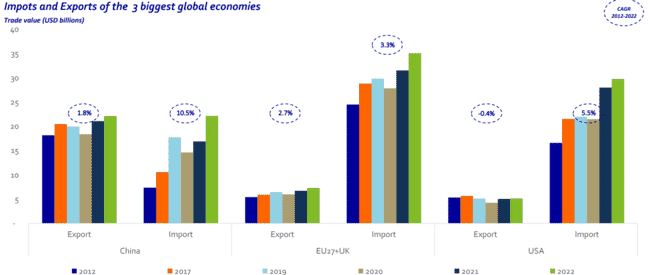

“This combination of factors suggests that it’s a trend that’s long overdue and they may well follow the European and US pattern: the EU has a seafood trade deficit of $28 billion, the US of $25 billion. We have fewer people and more resources, yet we still import most of our seafood – growing fish is rarely the highest value-added (ie income earning) option in a wealthy continent-sized economy,” Nikolik observes.

Despite this, he does see China’s market for domestically-grown seafood – notably carp and tilapia – as being likely to remain strong.

“They still produce 1.5 million tonnes of tilapia a year, but 10 years ago 90 percent of that would have been exported, while now only 20 percent is exported and they import whitefish from Vietnam, so are now net importers. Self-sufficiency might still be a government policy to some extent, but it seems that being a net seafood exporter is not,” he says.

China has gone from being by far the biggest exporter, to not even making the top 10 in 2022. © Trade Data Monitor / Rabobank

Global implications

Nikolik is rightly intrigued to assess the implications for the rest of the seafood world if China does follow the same pattern as Europe and the US – markets whose respective seafood deficits have, remarkably, been growing by over a billion a year since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“It creates huge opportunities on a global level. In 2017 China’s net seafood exports were worth $11 billion and now they are negative – which means that other countries have been able to capture that $11 billion market in five years. If the trend continues and China imports $11 billion net in the next five years, the rest of the world – most likely the typical exporters, such as Chile, Norway, Vietnam and Ecuador – will have a chance to meet that demand,” he predicts.

“And we can take it one step further. Europe and the US have a combined annual seafood trade deficit of $53 billion, despite having more sea area, less population and less seafood consumption per capita than China. It’s possible that China could follow the same parameters of production and consumption as Europe and the US and – if they did – who could produce the extra $50 billion of seafood? Even Norway only exports $15 billion net,” he points out.

It’s a trend that Nikolik first predicted in early 2018, in a report called China’s Changing Tides and he’s pleased that his forecast appears to have been vindicated. It’s also a trend, he notes, that could make for some huge opportunities for those countries willing and able to increase their seafood exports in the years to come. And he predicts that demand for salmon, shrimp and freshwater whitefish species in particular are all likely to see continuing growth. Although, he adds, that demand for other, more niche species, is likely to see an uptick too.

“The imports of US and Europe are so diverse – they import everything – and China will be at least as diverse as they have a more diverse kitchen when it comes to seafood,” he explains.

This makes for some amazing opportunities.

China's new demand for seafood imports presents a key opportunity for other global seafood players.

“For one, Chinese exporters will be exiting – someone else (either domestically or from elsewhere) will have to supply the US and Africa with tilapia for example. Will it make sense to farm tilapia in China to export to Africa if it’s been fed by soy imported from Brazil, then farmed by expensive people, on expensive land and then send it to Africa? It’s a lot of trade and a lot of work, especially if they have more profitable industries to pursue,” Nikolik says.

“But the even bigger opportunity is to find products to sell to China. That was already the case before 2019 – we were talking about China supercharging imports back then. Then they underperformed for two years following the pandemic, but now they’re back,” he concludes.