Briefly describe your aquaculture career

My first full-time position in aquaculture was at FRD Japan, a company that produces rainbow trout in a land-based recirculating aquaculture system (RAS). I joined in the summer of 2019, and my main role was to take care of trout from the egg to about 200 g. My tasks included feeding, sorting, checking fish health and growth, maintaining the facility and water quality control. I was also involved in R&D to determine the optimal conditions for trout growth. Then, my team leader invited me to become part of the company’s efforts to obtain ASC certification. Through this, I learned about world standards for responsible aquaculture and what fish farmers need to address in terms of sustainability. This was a valuable experience.

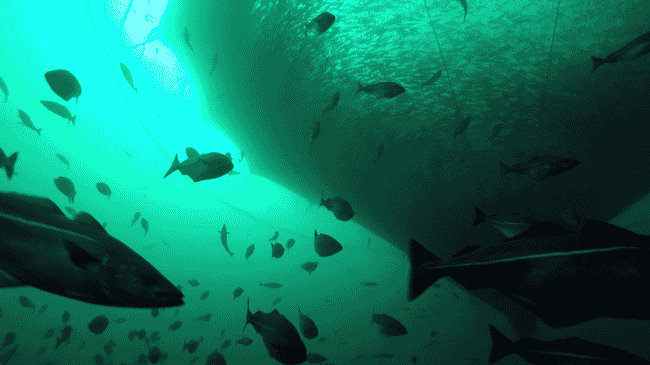

During my time at FRD, I became increasingly passionate about research-oriented work and moved on to my current position at the Department of Biological Sciences Ålesund at NTNU. I’ve been working here since summer 2020. My research focuses on the behavioural and distributional patterns of Atlantic salmon inside commercial-scale sea cages and how they interact with various environmental parameters.

What inspired you to start in aquaculture?

I’ve always enjoyed underwater activities, including swimming, synchronised swimming, snorkelling and scuba diving, since I was a child. I also love observing animals underwater and feel comfortable when I’m close to the water. Until I reached high school, I wanted to be a nature photographer, taking pictures and filming aquatic animals in the wild. I used to read a lot of photo books featuring wildlife from across the world. Those books were a huge source of inspiration.

As I got older, I wanted to work for something more closely connected to my life and in 2015, went to Norway for the first time as an exchange student. At Nord University in Bodø, I studied northern wildlife and aquaculture and found the latter much closer to my interests. I think it was around that time that I started to think aquaculture was the subject for me. It turned out to be a good choice because aquaculture keeps me close to the water, gives me plenty of time to watch aquatic animals and I can also contribute to our everyday lives by supplying seafood.

Banno's research focuses on the behavioural and distributional patterns of Atlantic salmon inside commercial-scale sea cages and how they interact with various environmental parameters

How was the transition from aquaculture in Japan to that of Norway?

It wasn’t a big transition but there were some changes. For example, my role in Japan was mostly a fish farmer but in Norway I’m a researcher. In Japan, I worked at a land-based RAS. Now I focus on sea cage aquaculture. But the main goal of my work hasn’t changed – to support the healthy growth of fish.

How has your experience at a Japanese RAS firm helped in your work in Norway?

Having worked at FRD and experienced the challenges that salmonid aquaculture is facing, I find it very easy to stay motivated in my current work. I have a clear vision that, as a researcher, I want to provide knowledge that can help fish farmers.

My experiences at FRD also made me realise the huge responsibility of rearing fish in tanks or cages. I was taking care of fish almost every day and felt very sad when I found some of them dead. In aquaculture, fish are a product that will eventually be eaten, but at the same time they are also living animals and I wanted the fish to live a good life in a comfortable environment. This feeling really helps me stay motivated here in Norway, as my work has a lot to do with maximising fish welfare.

During my time at FRD I also encountered some beautiful collaborative work between biology and engineering. In RAS facilities, there are a lot of mechanical devices, such as filtering equipment, different kinds of sensors and water pumps. It’s not just fish and water quality that we need to know about when growing fish in an RAS facility. We need to understand how the whole recirculating system works and this requires a huge amount of knowledge in everything – biology, chemistry, physics, mechanics and more. When I started working at FRD, I didn’t even know how a water pump worked. For me, the one intense year at FRD removed any boundaries I felt between the fields of biology and engineering. I started to feel more confident using many kinds of equipment. This has helped me a lot in my current role, because using different types of equipment – such as cameras, underwater robots, sonars and echo-sounders – for fish and environmental monitoring is a necessary core skill in my research.

What similarities and/or differences have you noticed between salmon farming in Japan and Norway?

It’s similar in Japan and Norway in the sense that salmon farming is a growing industry and a lot of new investment and technologies are making inroads.

One difference is the number of people and organisations that focus on, or are related to, salmon farming. In Norway, if you plan to start a new salmon farm, it’s highly likely that you can get everything you need within the country. Of course, there are some components that are obtained from outside the country, such as raw materials for fish feed. But in terms of knowledge, technology, products and services that are needed at salmon farms, and social and economic structures that support the further development of those elements, Norway has almost everything at home. I think Japan doesn’t have enough of this yet.

The production volumes are also completely different. Norway produces a huge amount of salmon and exports it worldwide. In comparison, Japan doesn’t produce as much but imports salmon and trout from abroad, mainly from Chile and Norway. Some projects have been initiated to produce salmon on a large scale but right now it’s still common for Japanese salmon farmers to operate on a smaller scale and focus more on distinguishing themselves from other producers by creating their own salmon brands.

I also see a difference in how education and industry are connected. In Japan, it’s seldom the case that students study salmon aquaculture and remain in the same field after graduating from university. Japan also doesn’t have many positions within salmon aquaculture right now. But in Norway, many students study salmon aquaculture-related subjects and most choose to work in the same field after completing their studies.

Another difference is the diversity of people in terms of gender and nationality. It depends on the type of position but, in general, Norwegian salmon aquaculture has a higher proportion of female and international employees compared to Japan. My department has researchers from Argentina, China, Germany, Japan, Norway and more.

If we look at the natural environment, Norway’s seawater is cold enough to produce salmon throughout the year, but Japan’s is too hot for salmonids in most areas, especially in summer. Japan also has limited time and space to grow salmon in coastal sea cages so alternative systems that can keep water cool enough are essential to produce a good amount of salmon year-round.

You are especially interested in fish behaviour and fish welfare – why these two areas?

Behaviour tells you a lot about the health and stress levels of fish. Careful observation of their behavioural patterns – such as swimming speed, direction, burst swimming, schooling, jumping and positioning in the tanks – reveals whether they are well, so-so, becoming weak, or are stressed. If we know the behavioural and distributional patterns of fish in their normal state, we can potentially make an early detection of an unfavourable environment, disease outbreaks or severe infection by parasites just by monitoring changes in behavioural and distributional patterns.

There is no universal definition of fish welfare, but one way to describe it is that fish which are healthy, growing well and living in an environment that fulfils their needs are experiencing good fish welfare. This also brings profit to the aquaculture industry because production will be more cost-effective and ethical. Fish behaviour is one of the indicators that can be used to evaluate fish welfare but we still have limited knowledge on behavioural patterns and their interaction with the environment, especially in commercial-scale facilities because monitoring thousands of fish in huge volumes of water is challenging. I’m interested in exploring how to evaluate the welfare status of fish inside commercial-scale facilities.

Describe a typical day in your current role

My days fall into two types – field days and office days. A field day would involve visiting a salmon farm that’s approximately 1.5 hours away from where I live. I usually monitor the salmon in the sea cages and wild fish outside with underwater cameras and a remotely operated vehicle. I’m currently working on a project to establish a new method of monitoring wild fish around sea cages, as these are one of the most important environmental factors that could affect the stress levels of salmon and influence the three-dimensional distribution of salmon inside sea cages. Usually I spend 4-6 hours at sea but it varies, depending on our plans and the amount of daylight. I’m very lucky because this commercial farm site is available with fish owned by NTNU so I can visit regularly.

In my office, I plan my projects, think about study design, write drafts of articles, read articles, have discussions with my supervisors and colleagues, test monitoring equipment, work on footage of fish and analyse photos. My workplace is really friendly and everyone is open to discussions. Until the end of January 2021 we’re working from home because of coronavirus, so most of our discussions and meetings are online. I’m looking forward to being back on campus and interacting with my colleagues again.

What’s the most interesting experience you’ve had in aquaculture to date?

One day I was in northern Norway on a sampling trip around salmon farms. I was a masters student collecting environmental DNA samples with my research group (Research Group for Genetics, UiT). We worked on the sampling for many hours, exposed to the fresh, cold air of the Arctic. Afterwards, we were lucky enough to encounter humpback whales and orcas and our trip turned out to be an evening whale watching cruise! It was an amazing experience, and reminded me that where we work is actually a home for many others, including those huge animals.

What is the biggest challenge facing salmon farming today?

There are many, but from my point of view, climate change, sea lice and harmful algal bloom (HAB) events are among them. The problems of sea lice and HABs can be partially solved by moving coastal sea cages to more exposed locations or land-based facilities, but these have different challenges. Climate change is a threat for any type of salmon farming. Increased seawater temperature will stress salmon and may lead to more frequent HAB events, which could cause mass mortalities. Extreme weather brought on by typhoons can affect sea-based and land-based aquaculture. They can cause structural damage to the facilities, damaged sea cages can lead to escapes and RAS facilities will have problems if basic infrastructure like the electricity supply is affected. Every system has different strengths, weaknesses and uncertainty. I remember one of my teachers in aquaculture said do not put all your eggs in one basket. I think diversifying aquaculture in terms of facility location, design, and cultured species is a good idea, as it would reduce the risk of damaging or losing too many fish. I also think diversification would help reduce environmental impacts.

Are there any individuals or organisations in aquaculture who you’ve found particularly inspirational?

Everyone I worked with and am working with today. Many of them put an enormous time and effort into their projects and I’m inspired by their attitudes. If I had to choose an organisation, I would say the Faculty of Biosciences, Fisheries and Economics (BFE) at UiT the Arctic University of Norway. I spent two years there as a masters student and got to know some very inspirational people including my supervisors, research group members, and friends I studied with. Working with them convinced me that aquaculture has huge potential to grow and that it’s an extremely exciting field to work in.

Banno's first full-time position in aquaculture was at FRD Japan, which produces rainbow trout in a land-based recirculating aquaculture system (RAS). © FRD Japan

Have you faced any particular challenges as a woman in aquaculture?

Fortunately not. There are sometimes some small physical challenges such as handling heavy bags of fish feed, but these are manageable when you get used to them. Here I’d like to thank my colleagues at FRD and NTNU for helping me with physically demanding jobs and anything that’s hard to do alone!

I think it can be challenging for women to work at fish farms if they have children. When we’re taking care of thousands of lives, unpredictable events can happen from time to time. We sometimes need to work very long hours until the problems are solved or we have to come to work in the middle of the night. These can be challenging for women with children, but support from someone in their private life and/or colleagues and leaders at work can make things a lot easier.

I believe there is no limit to what women can do in aquaculture if good teamwork exist.

What advice would you give to women who are considering a career in aquaculture?

My experience and the time I’ve spent in my career are still limited so I’m not in a position to offer advice. However, I can say that although aquaculture isn’t the easiest job, it gives you such joy when you achieve your milestones.

This applies to almost any type of job but aquaculture is teamwork. You can’t really do anything without your teammates. Growing fish, or anything that lives in water, and making a profit requires expertise from various fields so it’s worth spending time talking to your teammates and people who have different expertise. Also, please help your teammates when they’re facing any challenges. You need each other to make your everyday life enjoyable and succeed in your projects.