© Angelica Liljenroth

For gourmands and ecologists alike, the native European flat oyster (Ostrea edulis) has unrivalled qualities. For the former, it’s the ultimate eating oyster, and for the latter it’s an unrivalled eco-engineer.

However, after centuries of overfishing and habitat loss, wild flat oysters are now all too rare in European waters, while efficiently farming them is still proving challenging – hence the continued dominance of Pacific oysters on the continent’s seafood scene.

However, it’s a situation that Kent Berntsson, founder of Ostrea Aquaculture, has been trying to solve for close to two decades. His quest began with a PhD at the University of Gothenburg, and then, after several years working in other fields, at the request of a local businessman who was keen to start producing the prized oysters commercially.

They chose a location on the west coast of Sweden that gives them access to a variety of water types, allowing them to develop a unique approach.

“We not only have 17 years of research competence but we are also probably the only oyster hatchery in Europe which has access to deep Atlantic seawater, because we are close to the Norwegian Rhin, which goes down to 400 metres, which makes a huge difference in terms of water quality,” explains Berntsson.

“While our continental colleagues have to use UV treatment – which he tried in the past – we now have a more soft ecological way of treating filtering our water,” he adds.

Thanks to their access to deep Atlantic water, the company also benefits from the absence of oyster devastating pathogens, which are prevalent in more southerly European seas.

Process and progress

The team’s initial years were largely spent researching how to improve hatchery production processes. Significant results were achieved after a decade of trial and error.

“The survival rate of the larvae was the issue. Every now and then we had good production and then the next year we had nothing. But by 2018 we had our first really good results and started to scale the process to make more spat,” Berntsson reflects.

Indeed, by 2018 they had increased the average survival rate of their larvae up to 80 percent – an unprecedented breakthrough for flat oysters, as far as Berntsson knew. He attributes this to their unique location and move away from UV water treatment.

“Now we have a variation in the survival rate going from 100 to 50 percent at the worst, which is really a big achievement for us. Our progress was when we stopped using disinfected water and kept the seawater’s natural diversity of bacteria in the hatchery,” he explains.

Spotlight on spat

While the original plan was to grow market sized oysters themselves, when Christian Vorbeck joined as CEO in 2019 he decided to concentrate primarily on spat sales.

“We were producing very tasty and special oysters – while flat oysters in the UK and Ireland tend to be very dark, ours are pearl white. We can earn more money if we grow them on. But it’s a strategic decision, as cashflow is faster when we sell spat, rather than waiting three years to grow them to market size,” he explains.

They also hope to be able to capitalise on the growth in demand for spat caused by the burgeoning number of oyster restoration projects being launched in western Europe – thanks in part to offshore wind farm developers being required to undertake restoration projects as part of their lease agreements and in part due to the EU directive on biodiversity to drive restoration at sea.

The company is proud of how pale their shells are © Ostrea Aquaculture

Unique challenges

Ostrea should – in theory – be well placed to fulfil this need.

“We sell lots of spat to the Alfred Wegener Institute. We just did trials for them and they're very happy. According to the institute, the whole market for restoration in the North Sea and around Europe is going to explode and we hope to be one of the players to help this happen,” says Vorbeck.

However, their involvement has been limited by import restrictions in key markets, including the UK and the Netherlands, due to issues with their disease-free status.

“Our water treatment strategy is a potential problem because it doesn’t meet all the requirements for biocertified hatcheries,” says Berntsson.

Equally, although Ostrea is operating in Bonamia-free waters, Sweden has not yet been officially been designated as such – largely due to the small scale of its oyster sector.

Meanwhile, domestic legislation has also hampered their economics: unlike in most of Europe, where non-native Pacific oysters are allowed to be grown – and many hatcheries can use the sales of these to fund their research into natives – only the latter are permitted to be farmed in Sweden.

Ongoing on-growing

Despite the focus on spat, the company has continued to fine-tune their grow-out operations, as their ultimate goal is to produce premium oysters for discerning Swedish foodies.

In terms of techniques, due to the region’s low tidal they use hanging baskets attached to longlines.

“Our tide is only 20 centimetres here, so we cannot use intertidal systems,” Berntsson notes.

Like all those who’ve attempted to farm flat oysters, Ostrea has faced challenges in on-growing stage too, but have found that moving juvenile oysters to areas away from river mouths, which have a more stable salinity, has improved survival rates.

“A lot of the snowmelt from Norway and Sweden reaches the sea very close to our area and we can have high mortalities these years,” Berntsson explains.

“But after one year they are much more stable and it doesn't really matter if the salinity varies,” he adds.

The fragile nature of flat oysters is well-known, and Berntsson believes that farmers who are used to growing the robust Pacifics particularly struggle to adapt.

“You need to handle them more often than most growers are doing and flat oysters are much more sensitive, so you need to take care of the fouling,” he reflects.

© Ostrea Aquaculture

Plans to expand

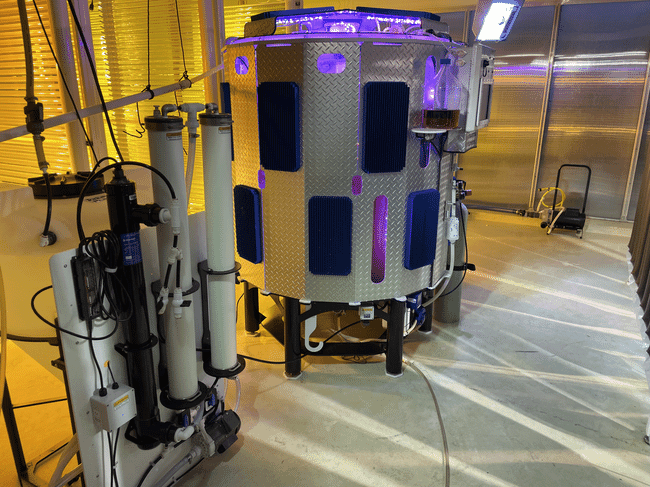

Ostrea is currently seeking an investment of 40 million Swedish krona (€3.7 million), to scale up their production of market-sized oysters to 100 tonnes as well as build a new hatchery capable of producing 2,000 tonnes of Ostrea edulis spat annually.

According to Vorbeck, around 80 percent of the funding would be allocated to capital assets such as boats, pumping systems, tanks and RAS units for larval settling.

“Our vision is to build a new hatchery and also help to build a Swedish oyster industry, because we have an advantage when it comes to climate change and water qualities compared to the continental Europeans,” he explains.

They also aim to help restoration projects across the continent – projects that Vorbeck believes are on the cusp of success, thanks to the breakthroughs in edulis aquaculture.

“Lots of work has been done over the last 10 years, but it seems that now is the time for it to explode. People need the spat now and that's why there's this high pressure and emergency meetings. If we can help others build the oyster reefs that improve marine biodiversity it's great to be part of that too,” he explains.

However, whether - and when – this will be achieved remains to be seen. Thanks in part to the enigmatic nature of flat oysters.

“There’s a saying that growing Ostrea edulis is not a science, but an art,” Vorbeck concludes.

© Ostrea Aquaculture