© Vicente Covarrubias

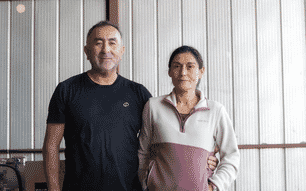

Over the past five years, the island’s seaweed sector has evolved from small-scale experimental farms into a coordinated red seaweed industry, with Tide – which was founded by brothers Hoce and Soid Fariñas, alongside Hoce’s wife, Gabi Reyes – being instrumental in this growth.

The brothers came to the island more than 20 years ago to study, after which Hoce set up a small seafood restaurant amidst the mangroves of Punta Guamache. It was there he met Gabi, a native Margaritan, who previously had a career in medicine and now leads Tide’s financial and administrative operations.

Since beginning to farm commercially in 2020, Tide has swiftly become the largest tropical red seaweed farming operation in Latin America, producing 1,500 tonnes dry weight this year, as the warm, nutrient-rich waters off Margarita and Coche islands provide favourable conditions for steady, year-round growth. And what makes their story especially compelling is not just their scale of production but also their approach.

As Hoce explains: “I would say that we don’t work with seaweed, we work with people – seaweed is the medium.”

The team has pioneered an organisational model of co-management – known as “cogestión” - with about a dozen full-time workers coordinating activities and transport.

Tide allocates plots – known as “parcelas” – to individual farmers, while taking care of the permits and regulations for them. Each “alguicultore” is responsible for planting, maintaining and harvesting seaweed, while Tide provides key inputs – including pre-seeded lines, shared boats, training, manuals and technical support.

The most productive farmers now earn between USD $800 and $1,200 per month – a life-changing income for most Venezuelans. Equally the people – mainly women – who seed the seaweed lines also earn a good income. As a result, crime rates have dropped significantly in the community around the farms.

Tide’s farmers currently operate nearly 90 parcelas across 10 hectares – although they now have a permit to triple this area. Each parcela is 50 m x 70 m and contains an average of 200 lines. Cultivation cycles generally last 45–60 days and each 25 m line yields an average of 70 kg wet weight per cycle, while some of the top performers achieve up to 150 kg.

Tide now works directly with 350 individuals, several of whom now operate family-run microenterprises.

On a visit to the farm it’s impressive to see that the lines are tight, organised and tidy, as the farmers are obliged to keep the area in and around their farm free from any free floating seaweed. The main species produced is Kappaphycus alvarezii, which is non-native, so the government is determined that farmers prevent it from dispersing.

© Vicente Covarrubias

Meanwhile Eucheuma isiforme (spinosum-type) is wild-harvested, as a native counterpart to E. denticulatum, which can be used for the iota-carrageenan industry.

Independent seaweed farmers also operate in neighbouring areas and Tide is one of the major and most consistent buyers of their crops.

Seaweed’s high water content makes drying a critical step after harvesting and Tide has invested in a 2 ha drying yard, where seaweed is sun-dried, typically within three days, with the capacity to handle 550 tonnes of fresh weight per month.

At full output, Tide's farmers currently produce 150 tonnes of dry seaweed for export (⅓ Kappaphycus and ⅔ Eucheuma) each month – a milestone in a region where red tropical seaweed aquaculture is still developing. Tide’s primary market remains international carrageenan processors in Chile and South Korea. Export shipments leave from Puerto El Guamache, with traceability and data provided for each lot.

However, as the carrageenan market conditions have been challenging, the team has been seeking alternatives to maintain economic stability.

“Four years ago, we began research to add value and started developing a pure, high-quality extract for the biostimulant market,” explains Soid, who is the commercial manager.

As a result Tide now operates a 600 m² processing plant that’s capable of receiving 5 tonnes of fresh seaweed every 150 minutes. The plant, which is only 10 minutes by truck from most cultivation sites, can produce 10,000 litres of pure Kappaphycus extract each day for their biostimulant line.

© Vicente Covarrubias

By producing both semi-refined extracts and branded products like GreenTide, the company aims to capture more value locally and establish Venezuela as not only a supplier of raw seaweed material but also a processor.

The balance of community-driven farming with centralised processing and export may hold lessons for other tropical seaweed regions seeking to grow sustainably, and Tide’s farmers are also able to influence decision-making processes through bi-weekly assemblies, which feature open discussions, votes on directives and the chance to address challenges collectively.

“There’s no hierarchy”, emphasises Soid, who aims to foster a sense of shared ownership and mutual benefit between the farmers and Tide.

They also incentivise ideas from individuals on ways to improve farming, which are tested on a small plot first and then rolled out across the group if successful, fostering a culture of professionalism, productivity and autonomy. And the provision of larger boats and trucks to transport the seaweed has improved efficiency and reduced physical strain on the farmers.

Although the Venezuelan seaweed sector faces challenges common to tropical aquaculture – namely environmental variability, logistical hurdles, and broader macroeconomic constraints – Tide has demonstrated that community-rooted organisation, coupled with technical infrastructure, can achieve commercial scale.

They have created the structures needed to link local labour with international demand and new product development. The company’s next frontier lies in balancing bulk exports with value-added processing, building markets for both dried seaweed and agricultural extracts. If successful, Venezuela could emerge not only as a supplier of carrageenan feedstock but also as a regional hub for seaweed-based product innovation.

© Vicente Covarrubias