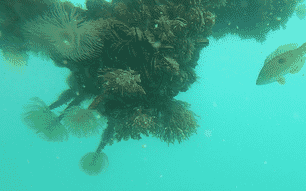

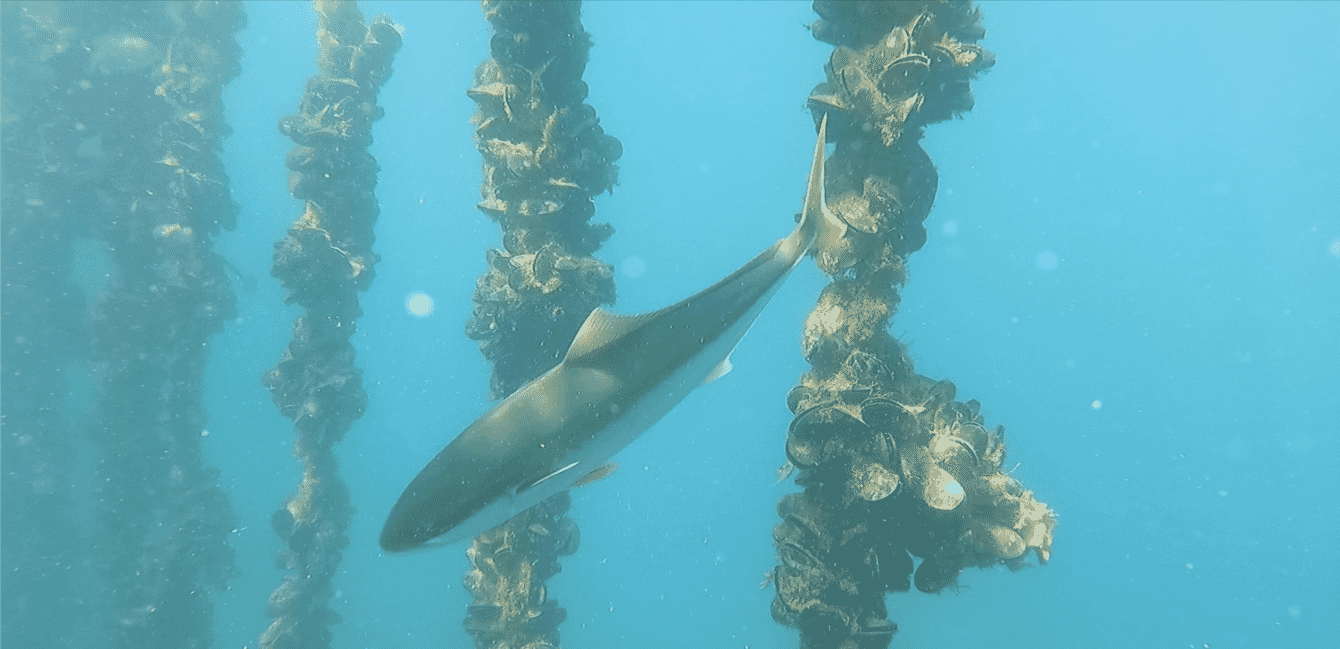

Researchers found the larvae of seven fish species were settling in mussel and kelp farm habitats, representing a level of diversity similar to natural habitats © Lucy Underwood / University of Auckland

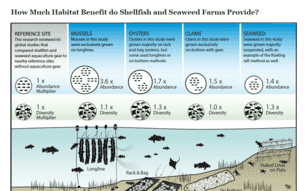

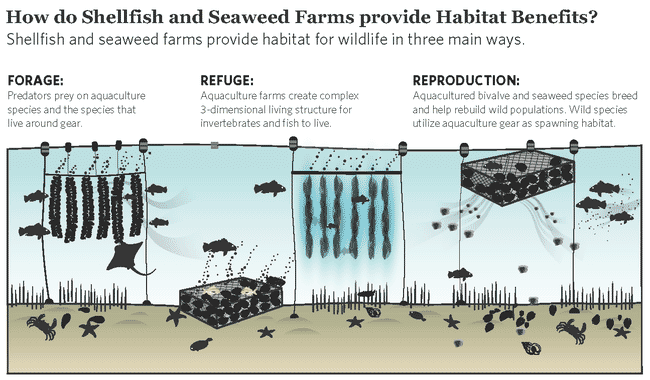

Wild fish are widely known to make use of shellfish and seaweed farms, often occurring in much greater numbers inside farms compared to adjacent natural habitats. While fish larvae are thought to settle and recruit to shellfish and seaweed farms, there is little published evidence to support this assumption, especially in temperature ecosystems. Targeting this gap in understanding, the University of Auckland and University of New England, with support from The Nature Conservancy, have been assessing the potential role of coastal aquaculture in providing habitat.

Parallel sampling methods have been adopted in the Hauraki Gulf in New Zealand and the Gulf of Maine in the United States to assess the effect of farm activity and local environmental conditions on the abundance and diversity of invertebrate and fish species. GoPro cameras and invertebrate collectors have been deployed, with unique results emerging from the research.

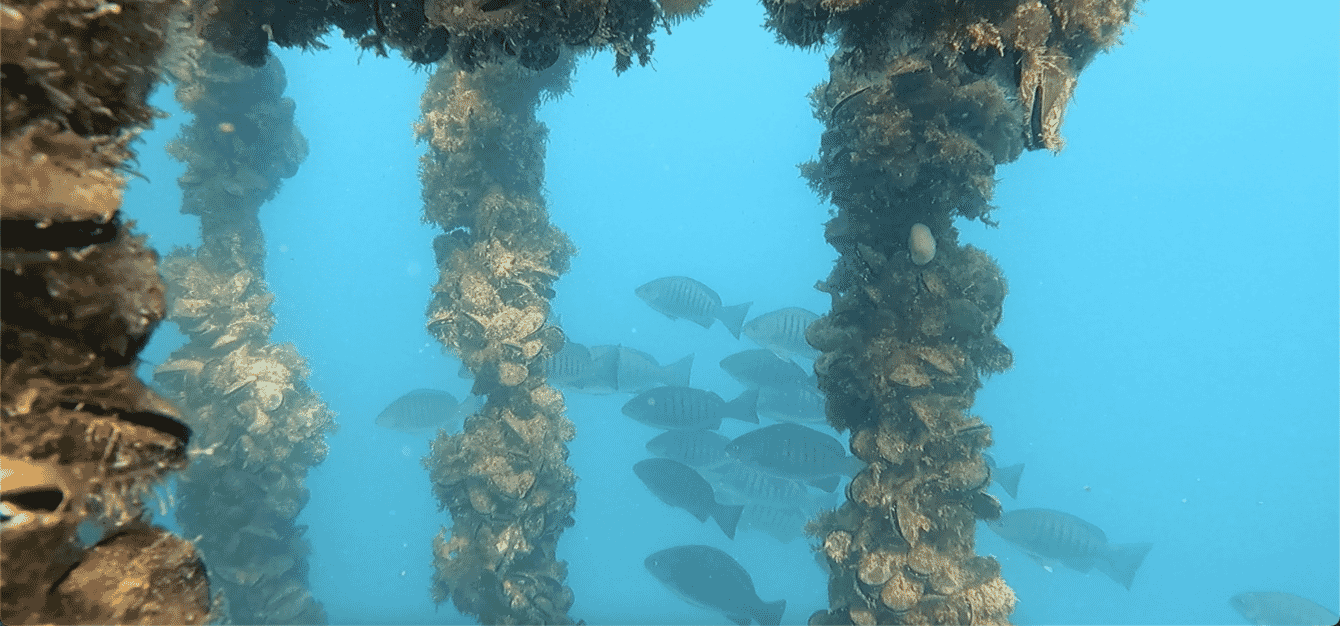

Shellfish and seaweed farms increase structural complexity in coastal environments, attracting fish – including fish larvae – to the shelter and foraging opportunities on offer. To assess the extent to which coastal aquaculture could be providing nursery habitat for juvenile fish in the Hauraki Gulf, Lucy Underwood and Andrew Jeffs of the University of Auckland measured the numbers of larval fish that were settling and establishing themselves in four different habitats: a farm with only mussels, a farm with kelp and mussels, a natural rocky reef with kelp, and soft sediment seafloor.

Sampling over the summer season, when most coastal fish are breeding, the larvae of seven fish species were found to be settling in both aquaculture habitats, representing a level of diversity similar to the two adjacent natural habitats. There were no differences in the mix of fish species settling within the four habitats, including where kelp was grown alongside mussels versus where mussels were cultured alone.

© The Nature Conservancy

However, both aquaculture habitats were found to have a much higher abundances of fish settlers than the natural habitats. Some of the key settling fish species, such as the common triplefin, had better survival and growth after arriving in the aquaculture habitats. In contrast, in the nearby natural habitat, the numbers of surviving settlers declined quickly, and their growth was slower than that of the juvenile fish in the aquaculture habitats.

A survey of adult fish found that 18 species were present in the aquaculture habitat, compared to only seven fish species in adjacent similar natural habitats. One species highly prized by anglers, the Australasian snapper, was found in much higher abundances in the aquaculture habitat and tended to be larger than their counterparts living in adjacent natural habitat, which could be explained by the differences in the composition and quality of their diets. Closer examination of the gut contents of snapper living on farms indicated they were feeding on the biodiverse marine life associated with the aquaculture operation.

The study reveals that both aquaculture habitats – a farm with only mussels and a farm with kelp and mussels – were found to have a much higher abundances of fish settlers than the natural habitats © Lucy Underwood / University of Auckland

Two papers about this research have been recently published:

- Underwood LH and Jeffs AG (2023) ‘Settlement and recruitment of fish in mussel farms’, Aquaculture Environment Interactions, 15, pp. 85–100.

This research is generating valuable information about the potential biodiversity benefits of seaweed and shellfish aquaculture in geographies experiencing ongoing growth in farming activity. Seaweed farming in New Zealand and the US, as well as in other temperate regions such as Europe and Australia, is a subject of growing interest. The New Zealand government and industry hope it can be a major contributor to new, sustainable growth in the country’s blue economy. As one of the biggest importers of seaweed products, the EU has highlighted 23 actions that could unlock the potential of this sector to meet expected demand.

Yet our understanding of the general principles and expectations for how seaweed aquaculture can provide benefits to the broader environment remains limited. The early results of this work suggest they might also be highly context-dependent, influenced at the farm site by local environmental conditions and management practices.

In the coming months, the results of further experiments in New Zealand will be paired with the results from the US to better understand how seaweed and shellfish farms provide habitat and how these benefits will likely vary across geographies, farming systems and farming approaches.