Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) are, as the name suggests, not native to UK waters and are in fact officially classified as an invasive non-native species. This places it in the same bracket of unwelcome intruders as Japanese knotweed and the American mink - both of which have devastating impacts on the UK's native flora and fauna. As a result, concerns have been expressed by some conservation organisations that the species may impact negatively on indigenous ecosystems and there have been calls to ban Pacific oyster aquaculture.

However, the new report offers a robust defence for the bivalves, noting that farming them is one of the most sustainable forms of food production and that they provide a valuable supplement to dwindling native oyster (Ostrea edulis) stocks. The report also notes that the UK’s regulatory ambivalence towards the species is at odds with the governmental support they receive in other countries.

The report, led by Martin Syvret of Aquafish Solutions, includes contributions from SAGB, JHC research, the New Economics Foundation, Atlantic Edge Oysters and The Fishmongers’ Company and the authors are united in seeking clarification for the future of the UK's Pacific oyster farming sector.

“If the UK is to rise to meet ambitions to produce more sustainable healthy food, including those targets set out in the English Aquaculture Strategy (Huntington and Cappell 2020) and the Blue New Deal action plan (New Economics Foundation 2016), then clarification of the legality and status of farming Pacific oysters must be provided to enable investment and provide security for existing businesses. Alternatively, if the UK seeks to retire its oyster industry, then clear guidance must be given to ease the exit of existing businesses and a pragmatic management strategy put in place to account for the ongoing presence of the species in British waters,” the authors argue.

Environmental benefits

One of the key defences offered by the report for the farming of Pacific oysters in UK waters relates to the range of vital ecosystem services that the bivalves provide – tackling climate change and improving water quality.

As the report explains: “Unlike other forms of food production, oysters and other shellfish farming have a very low carbon footprint, and can even be a carbon sink, locking carbon away in shells.

“By filtering all their food from the surrounding seawater, oysters actually clean up excess algae and other particles that result from high nutrient agricultural inputs. Clearer water enhances the growth of seagrass and larger seaweeds, in turn sheltering and feeding wide ecological communities.

“Wild Pacific oyster reef habitats themselves have higher biodiversity than alternative cleared or natural mudflats, with many native animals, including various birds, feeding in, on, and around the reefs. Best evidence suggests that a mosaic of different habitats that includes oyster reefs provides the optimum conservation outcomes for threatened water bird populations.”

While many of these services were previously provided by native oysters, the researchers point out that their stocks are in trouble for a number of reasons, making Pacific oysters all the more valuable from an environmental perspective.

“Europe has lost vast swathes of native oyster beds, and despite huge restoration efforts, disease and other pressures remain, and so it is unlikely that the native species will ever return to historical levels. Farming the alternative, more robust Pacific species, can fulfil many of the important ecosystem functions that have been lost with the decline of the native oyster. This doesn’t imply that one simply replaces the other, and evidence from both Poole Harbour and the Dutch North Sea shows that native oysters will settle amongst the Pacific oysters, actually aiding the restoration of the native species,” they argue.

The economic benefits of oysters

They authors also highlight economic benefits of the bivalves.

“In 2018, England and Wales produced only 1,000 tonnes of Pacific oysters, compared to 100,000 + tonnes in France. Nevertheless, the English industry supported 142 full time equivalents [jobs] in 2017, and in Poole Harbour, where 25-35 percent of English Pacific oysters are grown, this equated to a total economic activity of £2.6m, when both direct economic turnover and supply chain expenditure were taken into account.

“Still modest compared to neighbouring countries, the ambition of the English Aquaculture Strategy to grow Pacific oyster production to 5,000 tonnes by 2040 suggests the potential for an additional £10m of turnover in our coastal economies,” they observe.

Contrasting fortunes

The authors also contrast the hostility towards Pacific oysters from some quarters in the UK with the positive perception of them in other parts of Europe.

“England has a far more restrictive system for licensing shellfish aquaculture than exists anywhere else in Europe and this has been a significant factor in limiting the expansion of this sector,” they note.

This is despite the fact that the species is considered naturalised in all other European countries where it is farmed.

“All other European countries take a far more pragmatic view towards the management of Pacific oysters than the UK. They accept that it is present and that farming it will not add to the spread of the species given the high numbers of larvae that the wild populations produce,” they observe.

“Pacific oysters are breeding in our waters and there is no practical way to eradicate them, and so any restrictions in certain areas will not be effective… Even if it were somehow possible to totally eradicate Pacific oysters from the UK, research has shown that recolonisation of the UK coastline would occur due to larval drift from neighbouring European countries.

“Our European neighbours recognise that Pacific oysters can provide valuable ecosystem services as well as providing local economic opportunities,” they add.

As a result, the authors conclude that farming of Pacific oysters in the UK should be both given more credit and more legislative support.

“It is clear from this review paper that general calls for the prohibition of new Pacific oyster aquaculture sites are spurious in the context of any balanced assessment of the scientific literature. Moreover, cessation of existing sites would almost certainly be ecologically detrimental in the estuaries concerned, to an extent that, ironically, would be precluded by a precautionary approach.

“For some conservation organisations, calling for the expenditure of considerable amounts of public funding to protect indigenous ecosystems, in areas already temperature-compatible with Pacific oysters, might be considered legitimate and appropriate. However, globalisation, with the consequent movement of species, as well as climate change have resulted in few, if any, such extant systems, and all the science indicates that preventing the gradual spread of the Pacific oyster is no longer feasible. This is the reality which demands the adoption of more sophisticated conservation solutions of the sort which recognise not only the risks but also the benefits of the Pacific oyster in Britain,” they conclude.

“There is a great opportunity for the UK to act now, to adopt more pragmatic, forward looking management of our coastal ecosystems, for the ultimate benefit of the environment, while including a sustainable industry in the process. I hope this report may, in a small way, contribute to maturing the conversation between government, it’s agencies, and oyster growers, so that, after many years, an appropriate approach to Pacific oysters in UK waters can be adopted,” Dr Eleanor Adamson, fisheries programme manager with the Fishmongers’ Company’s Fisheries Charitable Trust, told The Fish Site.

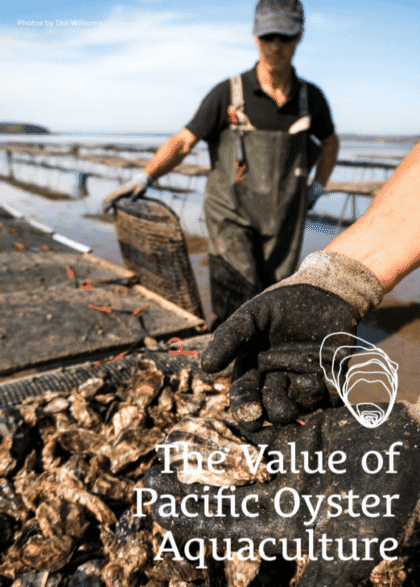

The full report, The Value of Pacific Oyster Aquaculture, can be accessed here.