© BTJ AQUA

The so-called “great lake” region, located in west of São Paulo and east of Mato Grosso do Sul states, produces about 65,000 tonnes of tilapia a year – just over 13 percent of Brazil’s annual production – thanks to a selection of large reservoirs that have huge aquaculture potential. There have been few disease-related issues in the region and conditions are eminently suitable for producing tilapia.

However, as Henrique Franco – co-founder of BTJ AQUA with his three siblings and their father in 2018 – reflects, the last few months have been stressful, as they have watched the water levels at their sites fall… by up to 15 cm a day.

“Water quality can be a big issue when the levels drop, especially in the smaller reservoirs or in shallow places. The organic compounds are concentrated, which can lead to eutrophication and algal blooms. The fish are still healthy, but it can lead to a reduction in fillet quality,” reflects Franco.

The cages on most farms in the region, are serviced by boats, but every farmer needs a shore base to access the boats for feeding and harvesting.

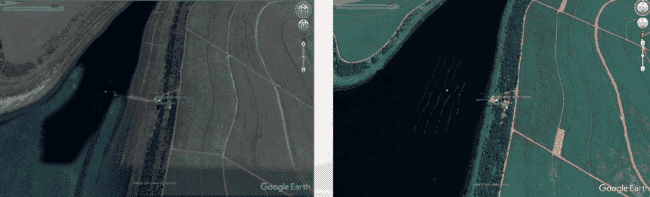

“We need to make 8 m wide causeways to reach the cages. As the water drops, we need to extend them, and some of ours are now 200 m long,” Franco explains.

As the reservoirs become shallower there are other dangers to contend with.

“The cages are normally in water 8-15 m deep but now trees [which were submerged when the reservoirs were built in the 1970s] are beginning to appear. They can damage the nets and cause fish to escape, and the environmental regulators don’t allow us to cut them down,” says Franco.

The prolonged dry spell in the region is the root cause of the falling water, but farmers feel aggrieved, as they were promised that the reservoirs would not be allowed to fall below a certain depth.

© BTJ AQUA

However, the hydro-electric companies that control the outflow of these water bodies are determined to keep generating power, regardless of the impact that this is having on the region’s fish farmers.

“We understand, as all farmers do, that there will always be some things that are out of our hands. But the regulators need to keep their promises. And the energy companies need to give us warnings if they are going to keep generating and bring the water levels even lower. But it’s almost impossible to get any information from these companies, after the state company CESP was sold to private Chinese companies, the communication got even worse,” Franco laments.

“Due to the lack of a clear communication we need to make more preparations in advance – maintaining and building ramps out to the cages; having replacement cages available; and buying boats to allow us to move the sites if the water levels drop too low,” explains Franco.

All of BTJ AQUA’s Farms are located in the Paraná River complex, which represents 53 percent of the national water storage capacity, but more recent hydroelectric plants are being constructed without any storage capacity.

“A notorious example of this is the Belo Monte Dam, which was built with the capacity to generate 11,233 megawatts (MW)/day, but it is actually producing an average of only 3,293 MW/day and 3,027 MW/day the last two years. In this dry season it is generating around 300 MW/day (2.67 percent of the capacity). As a result the state is needing to use coal-fired power stations, which were meant to only be used in emergencies,” Franco reflects.

BTJ AQUA currently produces around 10,000 tonnes of tilapia a year – from sites in three different reservoirs – and has ambitious plans to increase this to 30,000 tonnes a year by 2025. While they are still determined to achieve this goal, despite the water-related issues, it will require considerable investment.

“We are lucky – our farms are in good locations that still enable us to produce – but some farmers are being forced to stop production entirely. This has a knock-on effect, as they are selling their fish cheaply, driving prices down for the rest of us,” he adds.

In the last fortnight, the rate the reservoirs are falling has dropped from 15cm a day to less than 1 cm a day, thanks to heavy rains in the north of their catchment, but Franco is aware that the issues are likely to return.

“Right now, I’m feeling more optimistic, but I’m afraid of seeing that the reservoirs are falling so swiftly again,” he concludes.