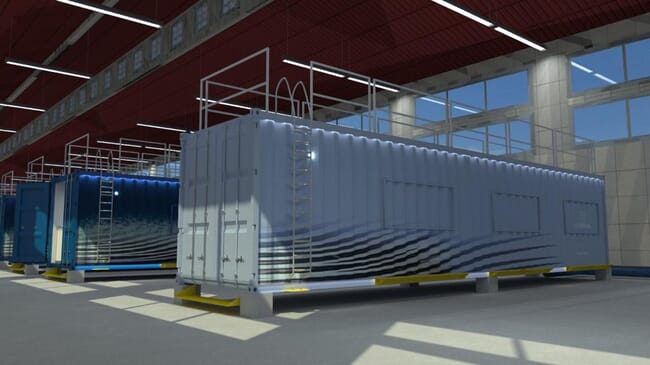

Shrimpbox is a modular biofloc shrimp farming system © Atarraya Inc

Hailing from Mexico City, Russek’s path to becoming an aquacultural entrepreneur has been far from conventional. The sector only came onto his radar after a hurricane in Oaxaca in 2005 led to destruction and mass unemployment. As a recent economics graduate he was inspired to head down to Oaxaca to set up an NGO with some friends in a bid the provide the locals with an alternative to travelling – often illegally – to the US to earn a living.

The area had a strong subsistence shrimp fishing tradition, but due to the short season and declining catches, Russek wondered if farming shrimp might be a more lucrative alternative. However, he quickly decided that setting up conventional commercial-scale shrimp ponds would “environmentally be a disaster” on this ecologically sensitive stretch of the Pacific, while it would also do little to help the area’s tourism sector.

He was also concerned by the high risk of disease outbreaks – a factor that made it hard to raise funds for shrimp farming ventures. So he decided to try to de-risk the proposition by creating a system in which disease was less of a threat and began to experiment with farming a range of aquatic species.

Russek designed the Shrimbox to be an environmentally sustainable and accessible farming platform © Attaraya Inc

“We worked with many species, including a multi-trophic system in which the water was passed from snook or snapper, to tilapia, to shrimp in a flow-through system. We started looking at the unsustainable nature of flow-through systems and we realised that the only two options were biofloc and RAS,” he explains.

“But RAS doesn’t really work in a place like Mexico, so we decided to settle on biofloc production of shrimp to simplify our operation, instead of trying to master three different species, three different value chains and three different market conditions,” he adds.

In 2013 Russek’s company, which had been christened Atarraya, established its own pilot shrimp farm, in nearby Puerto Escondido. Consisting of 39 lined biofloc ponds over 2 ha, it also includes a nursey, larviculture and algae growing zones, as well as housing the company’s first three Shrimpbox models. It currently has the capacity to produce 150-220 tonnes of shrimp a year and by 2016 they were able to master zero discharge biofloc technology.

By 2019 the company had started premium flying fresh shrimp from their farm to restaurants in Orlando, New York, Washington, San Francisco, LA and Las Vegas under the Agua Blanca brand.

“We wanted to know how much people were willing to pay for our product but in the end it was not a good business because flying it killed our mark-up and also killed our environmental claims,” Russek explains.

A change in direction

This inspired the team to investigate how to grow shrimp close to market and the solution they came up with was christened the Shrimpbox.

“Biofloc technology has many advantages over recirculating aquaculture systems but the problem is its complexity, it’s basically a biochemical endeavour. You need to track many variables, you need to make a lot of decisions and you need to train people. So in 2016 we started to build software to link data with decision making and communicate with the interactor – who could be a decision maker, or could be a machine,” Russek explains.

While they initially looked at automatic feeding systems they then decided to automate as much of the farming process as possible.

The first Shrimpbox prototype was built in September 2020 and the company then decided to set up a training centre in Indianapolis, to help increase their visibility and boost demand for the system in the US market. Their first harvest from this box-based biofloc farm is due in November, while new units are being established elsewhere too.

They currently have two operational boxes, but this will increase to 20 by the end of the year, according to Russek. Meanwhile, they are developing their own software and biotech, while also bringing talent into the company as well as manufacturing their own Shrimpboxes and designing their own Agua Blanca branding. As the momentum has gathered so has their desire to increase their visibility and their series A plans were published in August.

Russek is hoping to build and operate 20 Shrimpboxes by the end of 2022 © Atarraya Inc

Learning from others’ mistakes

Russek is under no illusions about the difficulties of growing shrimp close to the market, but believes he has learnt from the past mistakes of others. And he believes that other indoor shrimp have failed due to factors including discharge regulations, high energy and labour costs and their tendency to focus on RAS rather than biofloc.

“Companies are spending three or four years to build a 150 tonne RAS shrimp farm, which makes no sense. From a financial point of view, having a five year wait for returns doesn’t make sense unless you’re building an oil refinery or a nuclear plant,” he argues.

By comparison Shrimpbox offers nearly instant returns, being a true plug and play system.

“We signed our lease [for the Indianapolis farm] at the end of June and by the third week of July we already had our first Shrimpbox running,” he reflects. “Investors will start making money after only four to five months.”

Each box contains a control room at one end and a separate growing space with two 33-foot tanks that are stacked on top of each other © Atarraya Inc

The design

Each box contains a control room at one end, containing an automated feeding system, pumps, equipment to maintain oxygen levels and a waste collection system. This is separated by a partition from the growing space, which contains two 33-foot tanks, stacked on top of each other. All systems are linked to the cloud, remotely alerting customers when key tasks, such as topping up the feed levels, are needed.

According to Russek, it’s a very energy efficient design, due to the low air to water ratio in each box, which allows it to retain the heat more effectively than in a classic indoor shrimp RAS where the buildings contain a much higher air to water ratio.

“Our energy saving is 90 percent compared to typical round tanks in a greenhouse,” he notes.

Business models

Atarraya are keeping their options open as far as business models are concerned, and are likely to use a combination.

“We’re going to try three types of business model: franchise, contract and co-op. In a nutshell we don’t wont to be operating thousands of ShrimpBoxes. We want to create infrastructure and support our farmers with technology transfer, remote monitoring and go-to-market when our farmers need it – we can partner with other people who will be operating it. We think we can train people to become shrimp farmers within four weeks,” Russek explains.

So far there have been three kinds of people who have shown the most interest in the system, according to Russek. There are those who have tried and failed to grow shrimp due to the lack of support in the sector; distributors who have a niche market for fresh or live shrimp; and agriculture operators who want to further diversify their income sources and see the potential to use the waste floc for fertilisation or biogas.

A question of scale

According to Russek each box is able to produce 1.5 tonnes of shrimp per year, and 20 boxes is the minimum viable farm to allow for monthly harvests and fit with the supply chain. However, he adds that commercial-scale operators should aim to have at least 100 boxes.

Each Shrimpbox contains an automated feeding system, pumps, equipment to maintain oxygen levels and a waste collection system © Atarraya Inc

While the startup has been focusing on ensuring the proof of concept and improving their KPIs for their sensors and systems they are now looking to upscale production, which is part of the reason that that they are emerging from stealth mode.

So far they have been financed with angel investments from the VC world, but they are currently preparing to launch their bid for series B funding in late 2022/early 2023 and they looking to raise $15-20 million.

“Our investors have helped turn us from a shrimp farming operation into a tech company,” Russek points out.

The company aims to manufacture the units for $25,000 per box, to which shipping costs will be added.

“We are looking for a small markup for the box, but the business model is based on sharing any profits the farmers make,” says Russek.

Other sources of revenue for Atarraya will include selling the larvae and feed to farmers, while they are also hoping that some of their customers will sell their shrimp under the Agua Blanca brand.

Despite Russek’s ambition he is also aware of the fact that the business is still at an early, experimental stage and his plans – and partnerships – are therefore not yet set in stone.

In addition to selling Shrimpboxes, Atarraya plans to sell shrimp larvae and feed © Atarraya Inc

Operational issues?

Given that the Shrimpbox is relatively new there are still some question marks about how well the they will work across a range of locations.

“For a while we were very worried about the energy aspects of operating them outside Oaxaca, as we have the perfect weather here all year. We were worried about this in Indiana but our energy saving and insulation has been very effective,” he notes.

“Finding the right genetics was also very challenging – it was very hard to find honest suppliers of genetics. We have tried many genetics companies in Mexico and US, but we’ve tested all possible genetics and are now very happy. We have also tested every possible probiotic and every possible feed,” he adds.

The process of trial and error has been rigorous – Atarraya has already tested 53 batches of seed so far on their farm, with each batch being trialled in between eight and 20 ponds. Meanwhile the original ShrimpBox has completed 10 cycles.

“The farm is version 1.0 and Shrimpbox is version 2.0,” Russek explains. “We test first in our ponds, then in the Shrimpbox and we expect better performances in the Shrimpbox than in our ponds.”

Atarraya is targeting the US market, where demand for sustainable shrimp is expected to reach 100,000 tonnes per year © Atarraya Inc

Long-term goals

According to Russek’s research, demand for sustainable shrimp in the US alone is around 100,000 tonnes per year, and that is going to be Atarraya’s number one target market.

“The main challenge is how to manufacture 50,000 or 100,000 shrimp boxes? That will take time, even with unlimited capital. But in 10 years our costs will go down, and we have a clear roadmap to grow shrimp in the US at a cost lower than imported commodity shrimp. That’s what we will be using our series B funding for – to lower the costs as fast as we can. And in 10 years I’d like to be about 5 percent of the US market, producing at close to the commodity cost, but with good margins,” Russek explains.

“We also want to be working with more farmers, not just in the US – we’ve already had interest from Dubai, Milan, Australia and Canada. We want to create a dent in the market we don’t want this to be niche,” he concludes.