Aquaculture producers across Latin America are feeling the pinch from rising commodity prices and increasing energy costs

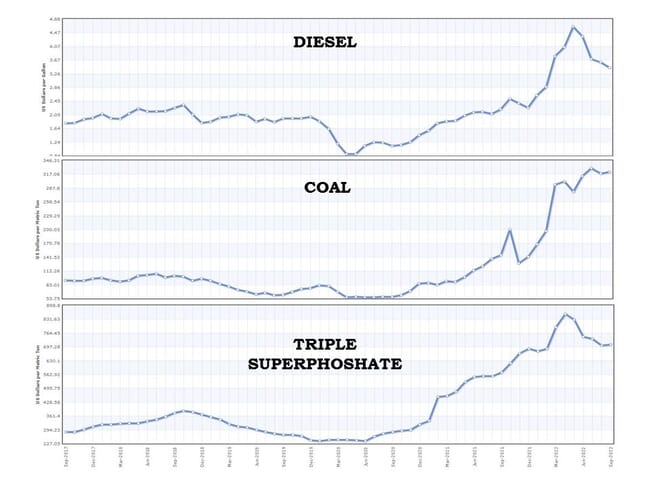

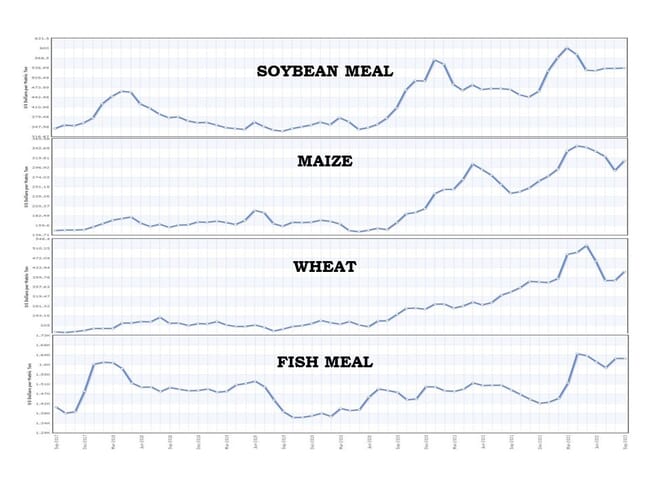

Over the past two years, aquaculture producers throughout the world have come under increasing economic pressure, which has now reached levels seldom seen in the history of our industry. Feed and energy costs have skyrocketed. A glance at global price trends for commodities that impact variable costs in most aquaculture industries provides all the background needed to explain the current situation.

Five-year (September 2017 to September 2022) price trends for some key components in a variety of aquaculture feeds are indeed sobering. Soybean meal went from less than $350 per tonne in September 2019 to roughly $600 per tonne in March of this year. Similarly, maize went from approximately $140 per tonne in May 2020 to $350 in April 2022. Energy commodities exhibited similar price trends, as did fertilisers.

For the past few weeks I have discussed the current situation with some of my colleagues and friends in the industry in Latin America. I wanted to use this opportunity to share their perspectives and highlight some research that may also provide strategies for producers to adjust their operational practices.

Prices for formulated feed have risen by almost 70 percent, while the price of whole fish has only increased by 20 percent © TUPEZ

As they see it

I asked Jairo Amezquita, the US Soybean Export Council’s (USSEC) aquaculture regional programme manager for Latin America, to share his observations on the current economic challenges facing the industry in his region. Originally from Colombia, Amezquita knows the aquaculture industry in Latin America better than anyone. His response was enlightening.

“In relation to the cost situation, it is clear that it corresponds to the global reality: recession, inflation, high freight costs, raw materials, and stability or decrease in the price of the finished products,” he replied.

“Additionally, climate change influences yields. Trends are toward intensification to reduce fixed costs and efficiency to control total costs. In this order of ideas, well-managed intensive production and recirculation systems become very important. However, they demand another type of financial, production and marketing management. Producers who do not adhere to these principles tend to leave the business, which allows concentration in a few operations with high financial capacity.”

Ramon Canseco Bremont, director of operations for TUPEZ, a pioneering and innovative tilapia farm located near Veracruz, Mexico, agrees with Amezquita, and shared the following assessment.

“I can confirm and comment that more than energy costs, what has impacted us the most is the cost of feed, and this results from the increases in raw materials due to market instability,” he reflected.

“Consumers have not accepted the proportional transfer of these increases in the market price of fish, in this case tilapia. Specifically, in the last two years, formulated feed has risen between 60 and 70 percent, while the price of whole fish has increased by only 20 percent, if anything, so these cost increases directly affect the profit margin of the business.”

When asked about consumer sentiment and its impact on TUPEZ’s markets, Bremont explained: “The demand has dropped a little, not only in the region but also in the country, especially due to the economy. Food in general has increased in price by two-digit percentages, including the basic grocery basket.”

Latin America is experiencing food inflation, which is putting pressure on fish demand

Bremont characterises the economic challenges Mexican aquaculture producers face in general as “the same. The main issue is the cost of feed, and this has generated uncertainty in some producers to continue growing their businesses. Due to these issues, many have chosen to maintain their production levels without growth since 2020.”

TUPEZ was one of the first companies in the Americas to adopt the in-pond raceway system (IPRS) technology that USSEC helped develop and promote. Regarding IPRS in the context of the current economic crunch, Bremont mentioned that the investment has bolstered their overall production by 30 percent, and commented: “It is important to mention that, like any production system, precise control must be kept and the various parameters must be monitored daily. The IPRS system definitely helps to lower production costs and has been the spearhead for the company's growth, but a large part of the margin now goes to feed increases. I believe that the challenge is in the stability of the commodities which, unfortunately, we cannot control.”

Another Mexican perspective was offered by Christian Alatorre, an aquaculture sales representative with VIMIFOS, one of the country’s large animal feed companies. He noted that a lack of technical understanding and management skills has held back many small-scale aquaculture operations throughout the country. Among this segment, economic pressures have aggravated a problem that already existed: a reluctance to invest in training and professional development opportunities.

Dr Carlos Espejo is a fingerling producer, educator and technical advisor with Genipez, in Viterbo, Colombia, and an aquaculture feed sales coordinator with the feed producer Italcol. He gave a similar assessment.

“Feed costs have increased by about 25 to 30 percent. Formulated feed producers depend on imported raw materials and face an increasingly expensive dollar against the Colombian peso. From January to date, the value of each dollar has increased by nearly 1,000 Colombian pesos (currently at around 4,800 to the dollar), which left producers with many problems. If we add to that an increase in energy and labour costs, any calculation of production of a kilo of meat increases dramatically. This forces the producer to be VERY efficient, to have better genetics and better production systems, such as the IPRS,” he observed.

In terms of any consumer resistance to price increases, he responded: “Notwithstanding the foregoing, the price of tilapia in Colombia is currently good, 11,000 pesos ($2.30) per kilo, and its future for export is encouraging.”

Feed costs have increased by about 25 to 30 percent and formulated feed producers depend on imported raw materials

Enrique Torres with Asesoria Y Acuicultura in Villavicencio, Colombia, produces fingerlings of a variety of species and does consulting and training in support of the industry. He summarised his perspective like this: “There are a lot of people leaving the business, but also a lot of people entering the business. However, many producers affected by the disproportionate increase in the cost of formulated feed are looking for alternatives to optimise production – in terms of energy use or the best use of facilities; or the best management of animals; or the use of alternative feeds. The expectations of greater exports of tilapia to the US have caused many people to enter the business (often without knowing and without proper advice) trying to produce fish to cover the shortfalls in production due to the amount of fish that could be coming out of the country.”

There are a number of IPRS facilities operating in Colombia, and when asked about this Torres replied: “The IPRS thing is a new technology, there are very big investments in it, but I haven't heard consistently better results than other types of production. In fact, there are many investments in IPRS made without adequate advice and that have problems.”

Regarding consumption trends, he added: “I would say that the consumption of trout has increased, while that of tilapia and cachama has remained stable, and with consumer prices on the rise.”

Prices for tilapia are rising, but consumption is remaining stable for now © Benchmark

Quantifying aquaculture profitability

Several years ago Dr Carol Engle and some of her colleagues (Engle et al. 2020) examined cost structures, productivity and economic efficiencies of various forms of aquaculture in the US, evaluating a number of species, production systems and scales of production. The authors, all esteemed aquaculture economists, constructed 58 comprehensive enterprise budgets in total, encompassing a number of species/production system/scale combinations. In addition to economies of scale, the costs of feed, capital, labour, management, energy and fingerlings were all identified as major factors impacting economic viability in most scenarios.

The authors used relative profitability scores to compare various species/system/scale combinations. These scores were calculated as (the market price minus the breakeven price, divided by the market price, with the result multiplied by 100. Basically, the score indicates the producer’s profit (or loss) as a percentage of the market price. For example, if a producer has a breakeven price of $1.29/kg, and the market price is $1.41/kg, the relative profitability score would be

((1.41-1.29)/1.41)*100 = +8.51 percent.

Conversely, if cost increases push the breakeven price up to $1.56 and the market refuses to pay more than $1.49, the relative profitability falls into negative territory:

((1.49-1.56)/1.49)*100 = -4.7 percent.

In any farming operation, the most important variable cost inputs should become the focus for improving profitability, whether they are feed, labour, electricity, fuel or fingerlings. In those operations where variable costs were higher than capital costs (as is the case for the majority of aquatic farms throughout the world) the authors found that improvements in feed conversion ratio and labour productivity offered the greatest possibilities for reducing production costs.

Takeaways

The conditions producers in Latin America are experiencing, as well as the conclusions presented by Dr Engle and her colleagues represent the new normal for aquaculture, at least for the time being. Improved profitability resulting from economies of scale is a reality in most forms of aquaculture, but current economic conditions serve to prevent all but the largest operations from expanding. Intensification of production can also lower production costs per unit, but this approach requires producers to make new investments in equipment, and increased spending on energy, labour and management.

Improved profitability resulting from economies of scale is getting further out of reach for many producers © FAO

Nature can suggest reasonable carrying capacities in pond production systems, and it is usually unwise to push the envelope too far in an attempt to intensify production levels. With margins already tight, it doesn’t make sense to elevate risks. In contrast, if ponds are already paid for, a low-density management strategy for tilapia, carp or catfish will obviously result in reduced harvests but in some cases it can also reduce costs per unit of production significantly, maintaining some degree of profitability.

The relative profitability score presented by Engle et al. (2020) is a simple and valuable tool for aquaculture producers to gauge their profitability. However, it requires good records and accounting practices, as well as an acceptance of day-to-day realities on the farm. I’m reminded of a pond-side discussion I had with a young catfish producer some three decades ago. I asked him what his average survival was across the farm, and he responded approximately 85 percent.

Intensification of production can also lower production costs per unit, but this approach requires producers to make new investments in equipment and other inputs © Dr Carlos Guevara Fletcher

Delving further, he stated his typical stocking rate was 10,000 fingerlings per acre per year, usually at a length of three inches (8 cm), and his farm-wide harvests were roughly 6,000 pounds per acre per year with continual (multiple batch) stocking and harvesting. When I asked how large his fish were at harvest, he responded that his processor was buying 1.5-pound fish, on average. I nodded, then watched the fish feeding for a couple of minutes. I then tried to explain that if he was harvesting 6,000 pounds of 1.5-pound fish, that would be about 4,000 fish. And, if he was stocking 10,000 fish each year and harvesting 4,000 that would be a survival rate of 40 percent. He politely told me my math was “wrong” and that I didn’t understand the business.