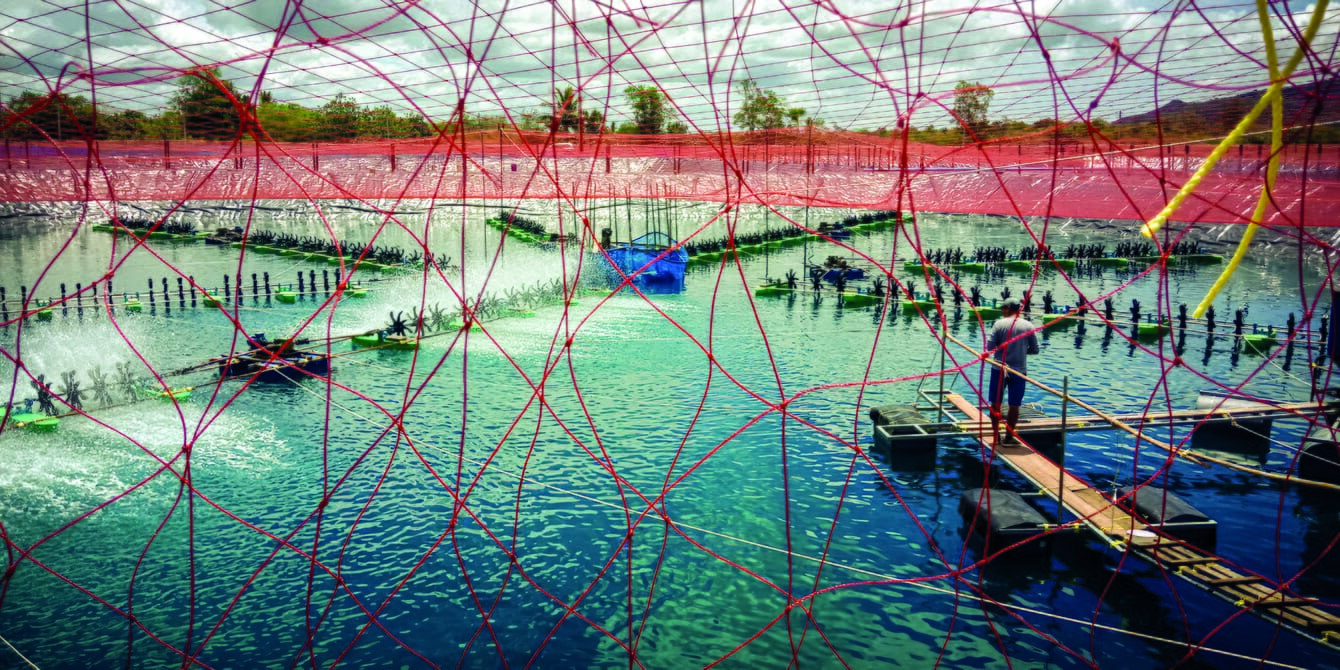

Rethinking stocking densities and biosecurity could help Asia's shrimp farms regain their place in the global market © FAI Farms

As the shrimp veteran explains, biosecurity practices on Asian farms were initially largely focused on preventing whitespot syndrome virus (WSSV) by using “the exclusionary principle”: namely by stocking specific pathogen-free (SPF) post-larvae and killing off/excluding the wild crustaceans – mainly larval shrimp and crabs – that brought the virus into the ponds via the intake water.

However, as he reflects, the advent of early mortality syndrome (EMS) – which is caused by Vibrio bacteria – in 2008 meant that farmers should have changed their tactics. Unfortunately, he argues, most of them have failed to do so – and instead have attempted to use disinfectants to exclude bacterial pathogens. It’s a practice that McIntosh sees as being fundamentally flawed.

“When the Vibrio come in the exclusionary principle is no longer applicable. Originally the use of disinfectants was trying to continue the exclusionary principle, but Vibrios are impossible to exclude, so we need to come up with another principle of biosecurity – which I call limitation,” he explains.

McIntosh says that shrimp farms can still be successful in the presence of different pathogens

“If you limit the pathogen load and the animal’s immune system is strong enough the shrimp can live with the pathogen without outbreaks of disease. This is what you see in South America, where you have low densities . You have pathogens in South America but you don’t have disease. But when you’re doing intensive culture, the intensity is a stressor – shrimp immune systems are less strong in Asian intensive systems compared to low density South American ones,” he adds.

McIntosh also argues that EMS is also misunderstood by many farmers, which is part of the problem.

“EMS is not an infection as most people understand infections – the animal does not get infected, but when the Vibrios colonise the waste, the shrimp moults, and even old feeds and the vannamei consume these items – and vannamei eat anything – they consume the toxin produced by the Vibrios,” he explains.

Keeping pond bottoms clean and free from waste can help keep bacteria levels low

“Once we realised this we realised the importance of keeping the pond bottoms clean – by not overfeeding and using shrimp toilets, which allowed the waste to be pumped out at frequent intervals to keep these bacteria levels low in the pond. And when you did that it was a very successful strategy,” he adds.

Other key factors have included advances in shrimp breeding programmes, which have helped to increase the shrimps’ tolerance to the toxin.

“There are still some outbreaks, but most of the serious EMS became history,” McIntosh reflects.

A new challenge

However, the next pathogen to have an impact on the sector was the microsporidian parasite Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP).

“We knew it was here in 1995, but it never was a disease until 2012. And by 2014 it was becoming a major disease in terms of costs and fail rates,” McIntosh explains.

This was, he argues, largely due to the intensification of shrimp farming that was widely occurring in Asia at the time. A trend that shrimp were struggling to adapt to.

“In my opinion EHP is a stress-related disease. When a shrimp is not stressed it can live with the disease. But when it gets stressed, EHP quickly destroys any hope of profitability. As farmers intensified their ponds and add more feed, their failure rare increases,” McIntosh observes.

And, he adds, farmers’ decision to try to combat the situation with disinfectants once more failed.

“Chlorine doesn’t help the situation as EHP is not down to the presence of the pathogen, but is a disease that affects stressed shrimp which are not able to cope with the pathogen,” he argues.

Scrubbing biofilms off the bottom of an EMS-infected pond in Vietnam

Seeking successful shrimp farms

McIntosh advises that the best way to learn how to beat these pathogens is not by studying failure, but by looking at what has allowed some farms to succeed, despite the challenges posed by bacterial diseases.

“In Thailand there are farms that are very successful that can compete with Ecuador and are even more successful than they were in 2010 [the peak of Thailand’s shrimp farming performance] – as genetics have helped build on the success of the past,” he notes.

However, he cautions that – without proper management – the application of genetics is insufficient to ensure success.

“I don’t think you can create any genetic strain that can overcome any genetic stress and keep an animal healthy in the presence of multiple pathogens,” he warns.

McIntosh believes that improving husbandry practices will help Asia's shrimp sector regain ground

McIntosh believes that, despite the challenges in Asia, those farms that adopt the right protocols should still be thriving. And he notes that the most successful farms are those that keep a sensible stocking density, of 85-120 shrimp per m2 – much lower than the 200 to 300 range that is currently the industry normal in Thailand – combined with avoiding disinfection, should enable survival rates to consistently hit 95 percent and FCRs to be 1.1-1.3.

“Even at this stocking density they can still produce 30 tonnes of 30 g shrimp per hectare in under 90 days – this is a winning combination. Hitting singles, to use American baseball jargon, not going for home runs,” McIntosh explains.

“These farms are not using chlorine, one of them is not even using insecticide and there’s EHP in the environment. It’s about being careful, making sure the biomass doesn’t get so heavy as to stress the shrimp. There is hope, as long as we keep promoting that the answer isn’t chemical, it isn’t disinfectants, it’s all about management,” he adds.

Probiotics are another non-chemical option. Although McIntosh admits that his attitude towards these has softened in recent years, he is not convinced of the merits of buying bacteria, given that so many beneficial bacteria are freely available and can be encouraged through good management techniques.

“In terms of using probiotics for trying to keep the pond bottom clean, I don’t understand that. I don’t believe in using probiotics to digest the waste, because it still goes into the water and produces blue-green algae and Vibrios. I much prefer the concept of physically removing the waste and then properly treating it rather than trying to use probiotics to digest it in the water,” he notes.

However, he adds that there may be scope for some probiotics to have a positive impact.

“If the probiotics stimulate the shrimp immune system, or bolster the gut’s microbiome, if they have functionality, then there may be applicable probiotics, but I need to see the benefit in terms of the cost. On my own farms I use almost no probiotics, but get high survival and growth rates. I’m not lacking because I’m not using,” explains.

McIntosh believes that farmers begin to see issues when they try to produce more shrimp than their facility can accommodate © Gregg Yan

While McIntosh’s experience is largely based in Asia he is also, unsurprisingly given its meteoric growth rate, also interested in South American shrimp farming and he believes the South American model is likely to continue to be successful, unless the producers become too greedy.

“Ultimately it comes down to greed – problems come from farmers trying to produce more shrimp than their facility can reliably and sustainably produce,” McIntosh argues.

However, he admits that he’s envious of Ecuador, as most farmers still have scope to increase production from four to 18 tonnes, per hectare, per year with simple modifications, such as the installation of auto-feeders and aerators.

Such modifications allow Ecuador’s farmers to increase their stocking rates from 12-15 per m2 and harvest once a year, to stocking 30 to 35 shrimp per m2 and do partial harvests. Thereby allowing them to harvest 16 to 18 tonnes a year, while limiting the maximum biomass to 4 tonnes per hectare.

This compares favourably – from a stress perspective – to some Asian ponds, which can have a biomass of up to 50 tonnes per hectare at any given time, as he explains.

“Ecuador hasn’t seen any EHP at the 30-35 shrimp per m2 strategy, they haven’t seen EMS (what they call extremely virulent Vibrio) on any mass scale. So the intensification on this scale seems to work. But if they keep adding to it – what I call vertical greed – they will, at some point, break the system.”

However, he points out that the luxury of “horizontal greed” – ie the gradual intensification of existing ponds – isn’t feasible in Asia, due to the small, fragmented nature of the farms.

“If our farmers in Asia want to get more from their farm they feel they need to pile more shrimp on top and that greed is where we get into trouble,” McIntosh observes.

“While some new systems allow for more intensive production and a higher carrying capacity, greed can still kill these systems,” he adds.

Such as process also requires more investment, so presents a much bigger risk.

“It’s my opinion only, and I’m not always right, but I’m trying to record observations that people should think about. And maybe experiment with ways of farming that aren’t just adding more and more and more,” he concludes.

*Click here to read the companion article on the dangers of disinfection.