“The entry of the salmon industry into the offshore aquaculture sector is supercharging innovation and scale, with many new projects in the pipelines, especially in Norway. A second parallel epicentre of offshore aquaculture innovation is China, where the space in coastal areas is restrictive while the demand for marine proteins is booming,” the report notes.

© Innovasea

“While these two development pathways are related, we expect them to progress in different ways. In Norway and the salmon farming sector, the transition to offshore is a natural evolution of the current business model, whereas in China, an industry transformation is needed for offshore farming to be a reality. But if this can happen anywhere, it is China,” it continues.

The report, which was compiled by the bank's leading seafood analyst, Gorjan Nikolik, details how offshore aquaculture can be both a new source of healthy marine proteins, and a “key business opportunity for many in the aquaculture and seafood industry”.

“If executed well, offshore aquaculture also has the potential to greatly improve aquaculture’s biosecurity, sustainability and animal welfare, while lowering its environmental footprint,” it states.

Spatial limitations

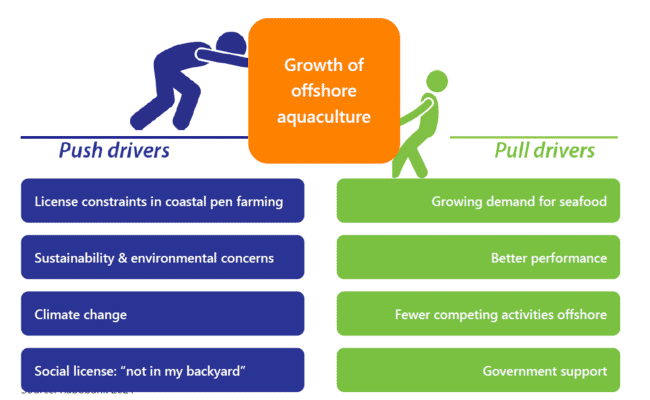

The report explains that, after decades of rapid growth, legislation, carrying capacity, environmental issues, pollution and climate change are all limiting the growth of coastal aquaculture.

At the same time, designs for new farms that can largely be controlled remotely are emerging – including floating, submersible and semi-submersible versions. While offshore aquaculture has been around for several decades, most of the early innovation took place in the US, Mexico and Central America.

“The difficulty of getting coastal aquaculture licenses in the US was the key driver for this innovation. However, despite the relentless efforts of many innovators and entrepreneurs, no large-scale offshore aquaculture has emerged so far. The reasons for this are numerous, but most important are: insufficient capital, lack of supportive legislation and government policies and a lack of marine fish species that have a large, established market and are suitable for tropical waters. What the innovators in tropical offshore farming needed was a tropical version of salmon,” the report explains.

© Rabobank

Salmon farming can be the catalyst for growth

The report notes that restrictions on coastal aquaculture in Norway are limiting its growth to a maximum of 6 percent a year. However, the Norwegian government’s development licence scheme – which was launched in 2017 – has sparked a range of innovative new farm designs.

“The fact that there is already a highly developed industry cluster with all inputs, skills and technologies available makes Norway the ideal location for this development. Not only are the large salmon farmers well capitalized companies that have the funds to execute the costly R&D for offshore farming, it also fits their business model. Offshore farming can be used as the last step in the farming process,” the report explains.

“Moving fish offshore for the last stage of the farming process means that the capital-intensive offshore structure is used efficiently at close to full capacity while license capacity is freed up on the coast, ensuring more growth potential,” it adds.

Although over 200 development licence projects have been proposed and over 70 accepted by the government, the report notes that Norway’s offshore salmon farming sector is likely to only produce around 100,000 tonnes by 2030.

Meanwhile the offshore sectors are gaining momentum in Scotland, Canada, Chile, the Faroe Islands and Australia.

“Climate change acts as an additional driver for offshore aquaculture in Australia, where warming coastal waters have shown a marked increase in recent decades,” states the report.

Offshore expansion in China

The report also looks into the latest innovations in offshore aquaculture in China, where spatial limitations are even more significant than they are in the salmon farming regions – due to issues including overcrowding, disease and pollution.

As the country’s capture fisheries have declined from their peak in 2016, and the growth of its freshwater aquaculture sector has dropped to 1 – 2 percent a year, so the incentive for increasing offshore aquaculture production has increased.

Moreover, the report notes that government incentives to increase domestic seafood production and China’s emerging expertise in manufacturing farming systems for Norway’s offshore salmon sector both lend momentum to the country’s own offshore aquaculture sector.

“The recent availability of farming technology, combined with Chinese government involvement, is creating fertile ground for offshore aquaculture,” the report states.

Limitations

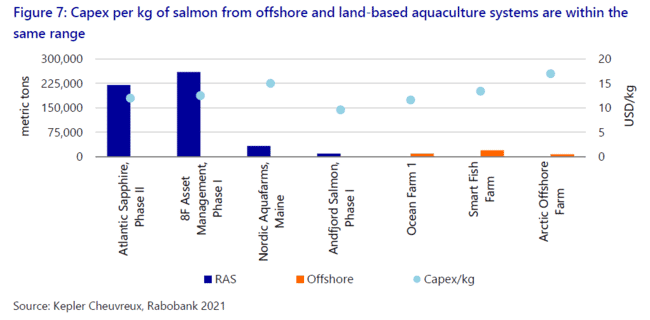

Despite numerous factors in favour of offshore aquaculture expansion, the report identifies three key limitations: high capital expenditure, operational risks and legislation.

1. Capex

The first of these means that the cost of producing fish in such offshore systems is currently in the range of $11 to $17 per kilo – a similar figure to land-based salmon production.

“The land-based projects have the advantage of being close to the customer and having a lower transport cost – although this needs to be balanced with higher operational costs (electricity and oxygen). Arguably, if there are no differences in variable cost, mortality and quality, it will probably be RAS, not offshore systems, that drive incremental salmon growth,” the report states.

“If capex eventually drops to USD 10/kg, which is arguably a realistic possibility, USD 10 billion of capital investment would be needed to make an additional 1 million metric tonnes of salmon (current production is 2.5 metric tonnes). There are projects that can lower this capex by utilising existing wind energy, oil or gas infrastructure, which could be used to moor the aquaculture cages and partially reduce the capex below the USD 10/kg mark,” the report adds.

In China, according to the report, the Capex is “perhaps half the cost or less for the large structures in the salmon sector”, while conditions in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea are much less harsh than the North Atlantic, suggesting greater potential.

© Rabobank

2. Operational risks

While the salmon sector is well prepared, from an operational perspective, to move to higher energy sites, the report notes that this is not yet the case in China, where farms tend to be smaller, while the development of feed, genetics and husbandry skills for species such as croaker and pompano “is decades behind salmon”.

“The government backed companies that manage offshore projects will have a steep learning curve in many different aspects. Consequently, the leap forward is China is not only toward offshore farming, but also toward large scale professional marine aquaculture farming,” according to the report.

“Nevertheless, given offshore farming’s high strategic importance, we believe the industry will continue to experiment, as long as there is government support. Many new projects will emerge in the coming years, but we also expect challenges on the operational side,” it adds.

3. Legislation

Legislation is flagged up as the third limitation.

“As many offshore aquaculture pioneers in the US have experienced – and still do – unclear regulations and ever-changing legislation can impede the path to scale,” it notes.

This means that smaller territories can have better hopes for offshore aquaculture.

“The Faroe Islands, a country with a population under 50,000 people, probably has the highest relative dependence on salmon aquaculture of any country in the world. Consequently it has the highest political will to enable offshore farming and, at the moment, arguably the most developed legislation for offshore aquaculture,” the report explains.

While China is likely to support the growth of the offshore sector, it could also lead to disputes with neighbouring nations.

Conclusions

The report ends with some reflections on how offshore aquaculture is likely to develop – both in salmon farming regions and in China – adding that it’s unlikely to take hold in countries which currently don’t have marine aquaculture sectors.

“Offshore farming is not a near – or even medium-term – opportunity for regions such as Alaska, Argentina, the Russian far east or South Africa, where water temperatures allow for salmon farming, but no farms currently exist,” the report argue.

However, it predicts that in the longer term, offshore aquaculture “will become one the key disruptive technologies in the seafood industry”.

Meanwhile, in the salmon farming regions “offshore aquaculture is a natural step forward for the industry that provides the opportunity to generate a gradual, longer term increase in supply”.

And the report concludes that China “could in a relatively short period, develop a sector that has a corporate scale to rival that of the European salmon farming sector”.

This would increase demand for quality feed, genetics and service vessels such as wellboats while also potentially reduce the activities of China’s much maligned fishing fleet.

“Our estimate is that, by 2030, up to 10 percent of salmon supply (100,000 metric tonnes to 300,000 metric tonnes) could be harvested from offshore farms globally. This production could also involve partial use of coastal farming. How offshore technology proliferates among other species will depend on how capital-intensive farms are and the development of Chinese offshore farming,” the report concludes.