Given his engagements in a wide range of tropical countries, Robins McIntosh is no stranger to doing business amidst political volatility.

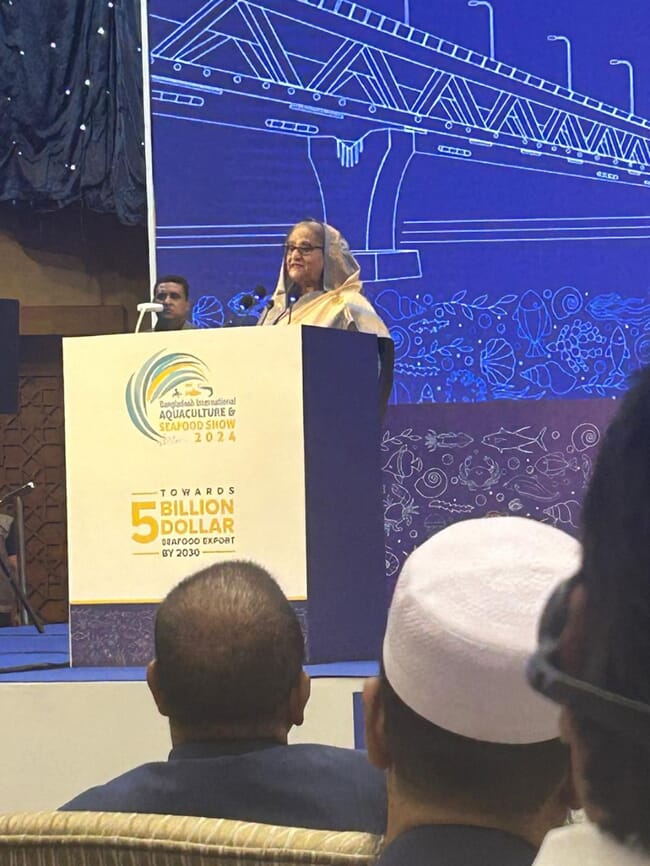

So in a year where political tensions have been particularly high across the globe, it’s perhaps no surprise that political upheaval has impacted him personally – starting with the student overthrow of Bangladesh’s prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, shortly after they’d shared a platform at the Bangladesh International Aquaculture and Seafood Show.

“I was with the prime minister for her last speech before she fled. She was launching a new initiative to make shrimp aquaculture a primary driver of Bangladesh’s economic growth,” he reflects.

McIntosh was advised to leave the country, and duly did so. More recently, events in Venezuela attracted his attention, when the Rincon family which runs Grupo Lamar, the country’s largest shrimp producer, were accused of trying to bring down the Venezuelan government.

According to McIntosh, the Rincons were one of the most forward-thinking shrimp operators in South America, who were not adverse to trying new ideas such as using specific pathogen-free (SPF) P. vannamei and at one time even entertaining the idea of culturing SPF P. monodon. He had hoped that Venezuela could become a major customer for Homegrown Shrimp USA - the company he established with CP in Florida - and remain a significant exporter, but is now much less optimistic.

He also sees the events in Venezuela as having effects in shrimp markets beyond broodstock.

“Lamar’s farms were producing around 60,000 tonnes a year. If these shrimp are not produced in 2025; other countries like Ecuador will find available markets in Europe and the USA that had previously been supplied by Venezuela,” he points out.

Can the shrimp crash be reversed?

The ongoing slump in global shrimp demand is well known, but McIntosh adds some useful context.

“The only people eating more shrimp seem to be Europeans – where year-on-year imports are up by around 10 percent. China is down 12 or 14 percent and the US is down by 3-4 percent. When you look at the Chinese numbers, that's disturbing because China was the driver of world shrimp,” he notes.

While he’s keen to see demand improve, McIntosh is doubtful of recent plans by the Global Shrimp Council to improve shrimp marketing in the US, which some have suggested could emulate the success of avocado marketing.

“Ten years ago, Americans didn't know about avocados, so you could have a marketing campaign to teach them about the avocado. But Americans grew up with shrimp, especially on the coast. We know they're delicious, but we also know they're pricey, so we don't eat them every day like we do with chicken. I’m not buying into the idea that you can convince people to pay more for their shrimp and buy more of it, given the constraints of the American consumer. I have always believed the way forward is by increasing efficiency and lowering costs,” he argues.

Hasina had ambitions to grow the country's aquaculture exports to $5 billion a year - a goal McIntosh thinks is unrealistic © Robins McIntosh

One positive trend McIntosh is noticing is a growth in domestic shrimp consumption in a range of producing countries, including Thailand, where he spends much of his time, working with CP.

“Of the 280,000 tonnes produced in Thailand, the local markets are taking around 100,000 tonnes, which is a significant amount of shrimp, and it’s a proportion that’s growing year by year. I think you see that in a lot of Southeast Asian countries, including Vietnam and in Indonesia. As the shrimp become less costly, the economies develop and it's a better market for the farmers who get a significant premium; sometimes as high as 25 percent over export farmgate pricing. he points out.

It's a similar story in other regions too.

“If you look at China, where sales are all local, the farmgate price is so much higher than anywhere else. And likewise, the local market for Mexican, Brazilian and Australian shrimp are much higher than the export market,” McIntosh explains.

“The export market is cutthroat - you're competing against Ecuador and India. The local markets aren't cutthroat like that. So that's where Ecuador has a disadvantage, and India somewhat has a disadvantage. They don't have a local market so are forced into export. India's talking about creating more of a domestic market, but when you're producing a million tonnes, you are basically going to be an exporter, especially if you look at the amount of investment in India towards export and all those processing plants,” he adds.

Trump’s tariffs

Many import-driven sectors – notably US seafood importers – have expressed their concerns about the US president-elect’s plans to dramatically raise trade tariffs. While McIntosh isn’t too concerned about the actual impact on shrimp producers and exporters, the concept of tariffs is clearly exasperating for him.

“People say you’ve got to protect the US industry, but that's a ridiculous statement. What industry are you protecting? Homegrown Shrimp and our 100 tonnes? Or the under 1,000 tonnes produced by farms in the USA? Or the shrimp fishing industry, which produces around 50,000 tonnes in total for a market of over a million tonnes?” he asks.

“Foreign shrimp actually benefit the US economy more than it benefits the country they originated from. You've got all the transportation, the cold storage, the retailers, the restaurants and all of the economy that runs off of imported shrimp is huge and it's not going to be replaced by domestic shrimp. You've got thousands and thousands of jobs that are tied to imported shrimp. They're not the enemy,” he adds.

An increase in disease

McIntosh is particularly concerned by the increase in bacterial diseases that shrimp farmers in all geographies are experiencing.

“We’re in an epic of major bacterial issues and new, more virulent bacteria, like Photobacterium damselae, new strains of Vibrio parahemolyicus that are implicated in white faeces disease and in the glass post-larvae disease prevalent in China and Vietnam.

Bacterial issues are the major cause of pond failures and increased production costs. These issues result in both higher pond mortality and serious size distribution issues.

He feels farmers are overwhelmed and without real guidance on how to deal with these issues that are very different from the viral issues of the 1990s and mid-2000s.

“If you ask farmers in Asia what their biggest problem is, they’re probably going to tell you it white faeces syndrome, which is a combination of EHP and Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Now, the Vibrio parahaemolyticus without the EHP not so bad. And the EHP without the Vibrio parahaemolyticus is not so bad. But you put the two together and you've got a catastrophe,” he points out

“But nobody really has the specific diagnostics for the Vibrio parahaemolyticus that is implicated in white faeces disease and, as a result, it can be spread into farms by post-larvae. When bacterial issues come from hatcheries the disease manifests vey fast. There need to be more efforts to fix the problem at the root and not just the symptoms,” he adds.

McIntosh argues that farmers are more interested in “gimmicks” than putting in the hard yards of farm management, and that this is also reducing their margins.

“In Asia the most farmers talk about the solution being the introduction of more robust genetics to control white faeces and the bacterial issues. But robustness comes at the expense of growth rate,” he points out.

“There maybe some truth in ‘fast grow, fast die’, and a lot of Thai, Indian and Indonesian farmers have gone to brands with slower genetic growth, but because they grow slower, costs go up,” he adds.

McIntosh is keen to decouple growth and survival rates, and believes it can be done.

“There's a huge opportunity for figuring out how to make fast growing shrimp robust. I guess that's probably where a lot of my effort is now, trying to figure out how to decouple growth rate and robustness. So you can have fast growing shrimp that survive white faeces, that survive some of these vibrios,” he argues.

McIntosh also points out that genetics is not the only way to create healthy shrimp.

“Shrimp nutrition should address robustness. Nutrition trials are done in a non-challenged environment, and today’s environments are challenging – with higher temperatures, high nutrient levels, resulting in higher levels of vibrio bacteria. Nutrition can modify what is defined as robustness and more nutrition trials should be done in challenging environments,” he observes

McIntosh sees climate change as the main catalyst for the uptick in bacterial diseases.

“We can't stop global warming, which is why the bacteria are so deadly now. Pond temperatures have gone sky high. We're getting rainfall. We're getting all kind of disruptions in the environment that give the edge to the Vibrio, to the bacteria. It makes it very, very difficult now and attempting to use chlorine only makes it worse because then you get rid of the good bacteria,” he points out.

However, he also blames the overuse of high protein feeds that result in higher levels of nitrogen in ponds.

“Protein is both a nutrient for shrimp and a toxin for a pond environment,” he emphasises.

On a more positive note is the fact that there are farmers in every country who have avoided the worst of the issues. Yet, much to McIntosh’s chagrin, their examples are not being followed more widely.

“I can go to Thailand and find farmers that grow shrimp for as low a cost as Ecuador. I can do the same thing in India. Every country's got great farmers, but 80-90 percent of the farmers are lacking. And they're the ones defining the story,” he argues.

Looking ahead

Despite his frustration, McIntosh is by no means without hope for shrimp, but sees the dichotomy between the major exporters and the rest of the world become starker.

“I think the outlook’s pretty bright for Ecuador. I think India has got some problems of their own making, but is big enough and wealthy enough that they will be there at the end. It's going to be Ecuador, India, and Indonesia calling the [export] shots. Vietnam has built a nice balance between white and black tiger shrimp with advanced value-added processing, but Thailand and others will be mainly focused on their local markets and providing high end value-added shrimp products for export,” he predicts.