There can be few people in the shrimp sector as well-known as Robins McIntosh. Despite two decades at one of the world’s largest seafood businesses, Charoen Pokphand Foods Ltd (CPF), he comes across as neither jaded nor corporate – a whirlwind of energy, he’s not afraid to express his opinions and on our zoom call he’s pacing in front of a virtual backdrop in Bangkok.

© Homegrown Shrimp

We’ve connected mainly to talk about Homegrown Shrimp, the farm – and farming concept – that’s he is in the process of setting up in Florida, and it’s clear that he’s determined to make it a success.

“I work at night with Homegrown Shrimp and during the day I work in Bangkok on both the Homegrown Shrimp and other responsibilities at CPF,” he says by way of explanation of his dual role of executive vice-president of CPF and CEO of Homegrown.

International trade restrictions

“I always wanted to do something in the US and was directed to find a shrimp culture opportunity by CPF – there was concern that there was a growing anti-import sentiment in the US, which worsened under Trump. We wanted to apply the technology we had developed in Thailand in the US,” he explains.

“Consumers in the US, Europe, Japan and China are all dependent on shrimp exports from tropical countries and growing product closer to home was becoming more popular,” he adds.

As well as a way for CP to hedge its bets, should it no longer be able to export its Thai-grown shrimp to key markets, there’s a sense that McIntosh was intrigued by the challenge – despite his knowledge that CPF was venturing where so many companies had previously failed.

Choosing a possible farm site

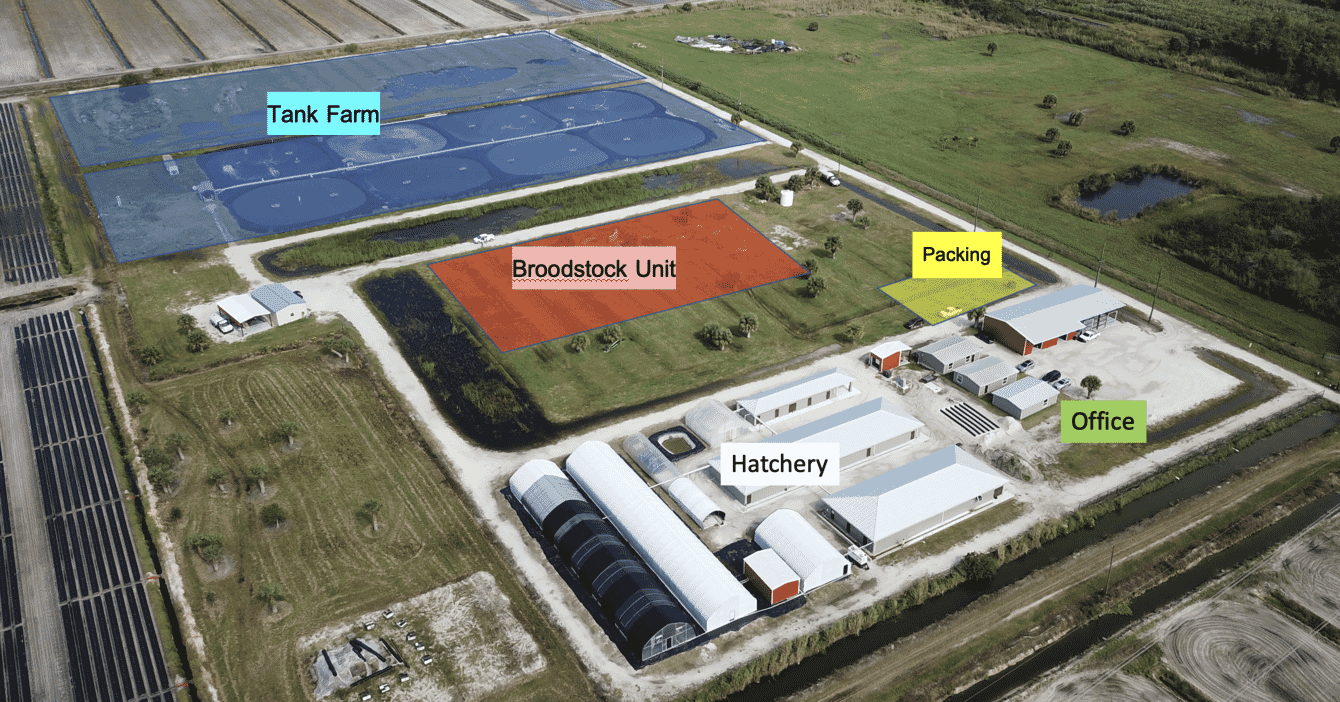

“We had ideas how to do it. I was directed to buy a farm or a company in the US but knew there was nothing on the scale we needed. I evaluated five or six in Florida and Texas and selected our site based on the fact that it had been a shrimp farm and had a history of producing shrimp. But had no history of profitability and at the time was run down and in disrepair. It was a piece of land with eight holes in the ground that had at one time been stocked with some shrimp post-larvae,” he explains.

The previous operators had tried to raise the shrimp outdoors, despite the seasonality of the location. CPF realised that this was a mistake, as even in south Florida there would only by 7-8 months of growing season if outdoor ponds were used.

“We wanted our shrimp to be available any time, all the time and have the experience to build a farm anywhere,” McIntosh reflects.

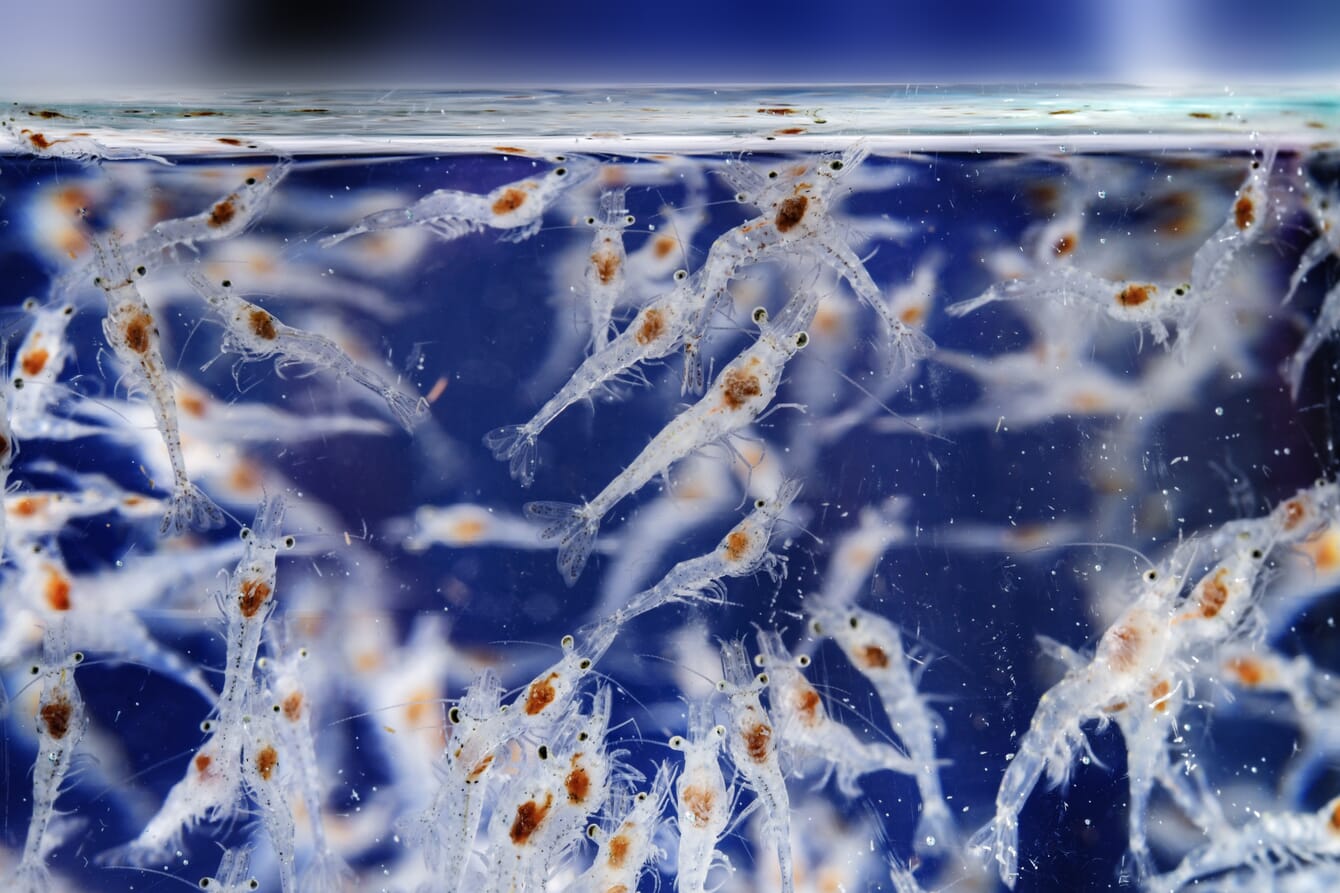

According to McIntosh, shrimp need to be produced year-round to ensure market development. In addition, to achieve the high levels of efficiency required, the facility needs to maintain a constant temperature between 30 and 31°C year-round and the only way to do this is with an insulated enclosure. And, finally, he adds there would “need to be available very fast-growing specific pathogen-free [SPF] healthy post-larvae”.

Paying the price

Indoor production has required a bigger budget than using outdoor ponds or tanks and although Homegrown Shrimp had the backing of one of the world’s largest food businesses, McIntosh notes that high costs of construction have proved to be challenging in developing a project with sustainable economics.

“It was much more expensive than we estimated – building costs, material costs, insurance costs – all costs farmers in the tropics don’t have. Homegrown Shrimp settled on using insulated metal buildings instead of what would have seemed to be the more reasonable cost of a greenhouse concept. The Greenhouse option was both expensive and restrictive in terms of area spans and greenhouses can only insulate to certain level of cold, so we settled on a metal building. The logic also was if an insulated metal building works in southern Florida, then such a building would work anywhere. We could grow shrimp in the snow, allowing fresh shrimp to be homegrown in any area of the United States, Europe, or Japan,” McIntosh observes.

Homegrown's farming techniques

The current farm is essentially a two-phase pilot project and Homegrown Shrimp aims to produce 80-90 tonnes of vannamei in the first phase and ramp this up to 180-200 tonnes in the second. Construction of the former is due to begin in October and be ready to stock by December, with the first harvest due in March or April 2022.

Homegrown plans to stock shrimp at a density that will result in harvests of 25-30 gram shrimp at a yield of 5kg / m3. The plan is to initially harvest two tanks a week, increasing this to five a week in phase two.

“Initially the shrimp are for white tablecloth restaurants and consumers who can appreciate the quality only fresh, never frozen shrimp can provide. And appreciate the shrimp are from a US or local farm, with no chemicals, antibiotics, or labour issues, and uses sustainable feeds and captures or recycles all wastes and water. The farm is not coastal and has none of the issues associated with our oceans or coastal environments. Homegrown Shrimp will not compete with commodity shrimp – Asia and South America produces the broiler chickens, we’re producing the high end pheasants,” he reflects.

Looking further ahead McIntosh sees potential to produce 800-1,000 tonnes a year, and with increased production and advances in the technology, he argues, the costs will decrease, and the shrimp made available to more and more shrimp-loving Americans.

“In the long-term technological developments are deflationary. We’re at a high point of cost, and the cost will fall. I doubt we’ll ever be able to compete with commodity shrimp, although as we increase production the price will fall and the demand increase,” McIntosh notes.

In terms of production Homegrown Shrimp is implementing technology and techniques like those used by CPF in its SPF and nucleus broodstock breeding centres in Thailand. It is anticipated that by keeping the site disease-free, the same efficiency will be maintained – ie 5 kg/m2 and over 90 percent survivals.

“These broodstock facilities do not use pumped seawater; they recycle the same water that had initially been made from concentrated salts. Disinfection is not needed constantly, so the water remains mature which is known to be healthier for shrimp. There are no green TCBS colonies which are known to be the bad bacteria,” McIntosh explains.

Over time he hopes to make the site increasingly efficient but is realistic about how far this process can go.

“Producing 5kg of shrimp per m3 is our target – maybe we can get 6 kg, but we’re not going to get 12 kg, with what is essentially a modified biofloc technology,” McIntosh notes.

“At the moment we’re using 60 percent of the facility to grow shrimp – 40 percent is used for things like water recycling and walking space between tanks. With the faster growing shrimp lines that will be used, we plan for four crop cycles a year. This would which equate to 20 kg per m3 from 60 percent of the space. Maybe in time we can increase this to using 80 percent of the building. And – eventually – as the technology improves in RAS, migrate to deeper tanks with higher yields, increasing the yields to over 80-100 kg/m2 per year. This would certainly help offset the high cost of the building,” he adds.

Lessons from the past

The onsite hatchery has been operational for two years, and is capable of producing 10-12 million post-larvae (PL) a month, throughout the year, although McIntosh points out that most of the sales take place between March and July.

“Historically US producers come and they go. The industry needs more success to build a more sustainable industry where business make profits and continue to grow,” he says.

According to McIntosh, there’s a common denominator for these companies folding.

“Many startups have turned into startdowns the next year. Why have there been so many failures? Largely because they weren’t able to source high-quality PLs, because there were none available. The correct, healthy, genetically faster growing stocks were not available to US and European growers,” he argues.

However, McIntosh believes that now HGS’s hatchery is producing its super-fast growing “Bolt” line of shrimp, more of the startups will have the chance to survive and prosper.

“We have the fastest growing animal on Earth. They’re SPF, they’re produced in biosecure units and have been selected for high performance. They grow fast and big. They may not be suited to outdoor ponds but are ideal for indoor biosecure production,” he says.

Homegrown’s post-larvae are also being produced from non-ablated females. According to McIntosh, this increases the robustness of the resulting PLs.

And he sees Homegrown's success as being good for the wider industry, which is also good for HGS.

“If we’re able to supply more good animals to producers in Europe and the US, more people will succeed in the industry and demand for our PLs will grow,” McIntosh explains.

“Without good animals you can’t test your technology. Without good animals the industry will stay small,” he adds.

This is the reason why HGS is willing to not make a profit on PL sales, according to McIntosh, as it is imperative the US and European industry become stable and profitable if the land-based American and European shrimp industries are to grow.

Future trajectory

McIntosh believes that there’s scope to improve the speed of shrimp grow-out even further and, in the long term, CPF aims to bring the culture period to grow a PL to 20-25 grams from the current 70-80 days down to 50 days.

Looking ahead, he sees the indoor shrimp sector evolving through a combination of factors.

“We need PLs with high health, that grow well and don’t die; we need high performance feeds that are priced suitably for farmers, not hobbyists – now in the US we’re paying higher prices than farmers in South America and Asia. The industry needs to size, so quality feeds can be available with competitive costs of Asia of around 1.20 USD/kg of feed. Only through industry growth will the price decrease,” he notes.

Why do shrimp get the blues?

McIntosh also observes that many of the cultured indoor shrimp appear blue – which is suboptimal.

“Contrary to what the farmers believe this blue colour is not a sign of health – it’s a sign of stress and a lack of certain pigments in the feed/environment. When you cook these blue shrimps, the lack of astaxanthin pigment becomes obvious, as the cooked product is a dull pink, and not bright red. This issue of stress and lack of pigment maybe a contributing factor to reduced survival faced by many indoor shrimp farms,” he reflects.

McIntosh is looking forward to the day when the shrimp sectors in North America and Europe are large enough to merit major shrimp feed players building feed mills in these regions. In the meantime, HGS will continue to rely on feed from CPF’s mills in Thailand and continue to work towards feeds made from sustainable feed ingredients.

“In the end we hope the legacy of Homegrown Shrimp is to provide a blueprint for successful shrimp culture in the USA, Europe, Japan and any other location that wishes locally-grown shrimp, produced with minimum environmental impact, without chemicals or drugs, and at more and more competitive pricing,” he concludes.