A recent paper published in Aquaculture Reports suggests that shrimp imports to the US are falling short of consumer safety standards. Researchers in Baton Rouge, Louisiana went to multiple grocery stores in the region and purchased a variety of fresh and frozen shrimp products originating from Vietnam, Thailand, Ecuador, China, India, Indonesia and Bangladesh. They then screened the shrimp for sulphite exposure and veterinary antibiotics that have been banned in the US.

Lab tests showed that most of the shrimp samples contained residues of oxytetracycline, nitrofurantoin, fluoroquinolone and malachite green, antibiotics that are restricted or banned under current US food standards. They also found that many of the shrimp samples tested positive for sulphites but were under the maximum regulatory threshold. However, none of the products contained a sulphite warning label, something the researchers felt was an oversight.

According to the researchers, these results demonstrate that the existing screening protocols and enforcement measures for US shrimp imports are insufficient. It also shows that shrimp producing countries need to take additional steps to restrict antibiotic use.

Background

As shrimp production intensified in the 1970s and 1980s, many farmers relied on antibiotics to combat disease outbreaks and promote growth. They also embraced sulphites to prevent and treat melanosis, or black spot. However, using antibiotics as prophylaxis has detrimental effects. Overuse of antibiotics can lead to drug-resistant bacteria, treatment residues can leech into the surrounding environment and many antimicrobial compounds can remain in shrimp biomass and be passed up the food chain. Sulphites also carry human health risks, especially if someone has an allergy.

In response, many shrimp-producing countries took steps to curb antimicrobial and sulphite use. In North America and the EU, both major importers of farmed shrimp, the use of antibiotics in aquaculture is strictly regulated. In some cases, antibiotics like chloramphenicol and nitrofurantoin have been banned outright. For sulphites, the United States and EU adopted strict labelling requirements. Products that have been treated or exposed to sulphites must have a warning label for consumer safety.

Though these steps have improved the safety and quality of farmed shrimp, over-reliance on sulphites and antimicrobials is an ongoing issue in shrimp-producing countries. In the US, the FDA has the authority to test and reject shrimp imports if they contain antibiotic residues or sulphites over the minimum allowable threshold. However, due to budget constraints, the FDA can only test 2 percent of the country’s shrimp imports. Despite restrictions and bans, antibiotic and sulphite residues still make their way into shrimp imports and onto grocery shelves.

The study

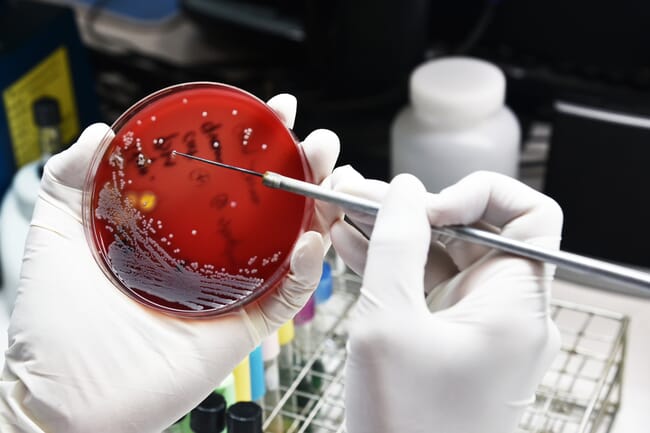

The researchers purchased 56 different types of imported shrimp from multiple grocery stores across Baton Rouge, Louisiana. They also purchased shrimp with different expiration dates to ensure they got multiple lots of imported shrimp. The countries of origin for the products were India, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, China, Bangladesh and Ecuador. They noted that none of their samples had allergy warnings or statements about sulphite exposure. They then used sulphite detection kits and ELISA kits to test if the shrimp had been exposed to restricted antimicrobials. They specifically tested for oxytetracycline, nitrofurantoin, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolone and malachite green.

Key results

Testing with ELISA kits showed that multiple veterinary drug residues were present in shrimp imported from the listed countries.

- 5 percent of samples tested positive for malachite green, an antibiotic that has been banned in aquaculture, as it is a cytotoxin and because of its association with liver tumours. These imports originated in Vietnam and Indonesia.

- 7 percent of samples tested positive for oxytetracycline, which it not permitted in US aquaculture. The shrimp found positive for oxytetracycline were sourced from Thailand and China.

- 17 percent tested positive for fluoroquinolone, which has been banned in the US due to its links with renal failure and cardiac arrhythmia. These products were sourced from Thailand, Vietnam and India.

- 70 percent tested positive for nitrofurantoin, an antibiotic that was used as a growth promoter in livestock until the 1990s. It has been banned in the EU since 1995. However, the compound is difficult to biologically monitor. The positivity rate in this trial was confirmed by multiple screenings. These shrimp originated in Bangladesh, China, Thailand, Vietnam and India.

- All of the shrimp tested negative for chloramphenicol, an antibiotic that has been banned as it is a carcinogen.

The researchers noted that all of the countries except Ecuador had shrimp with sulphite residues between 10-100 ppm, which is below the FDA’s regulatory threshold (the maximum allowable concentration for sulphites is >100 ppm). However, none of the products contained a sulphite warning label. This shows that shrimp exports are not being subjected to enough tests. The researchers felt that this presented a consumer safety risk – it also suggests that US importers are not adhering to current labelling requirements.

These results are not wholly surprising – though the FDA only tests 2 percent of shrimp imports for banned veterinary drugs, the organisation rejects multiple shipments each year. This shows that antimicrobial residues are still a major problem in imported shrimp.

Recommendations for producers and consumers

For US-based shrimp importers, the results show that the existing labelling and antibiotic testing infrastructure is insufficient. The drug residues present a food safety risk to consumers if they are allergic to certain classes of antibiotics. There is also a chance that imported shrimp could introduce drug-resistant bacteria into the food chain. Testing methods for food imports must be improved and made a greater regulatory priority.

For shrimp exporters, efforts must reduce antibiotic use must be scaled up. The researchers suggest that shrimp-producing countries prohibit the sale of banned veterinary drugs. At the farming level, technicians must receive training on antibiotic stewardship. Researchers should also identify alternative treatments for bacterial disease and create methods to ensure that shrimp that have been treated with antibiotics are free from drug residues at harvest.

The researchers suggest that consumers with a sulphite allergy or sensitivity purchase shrimp that are guaranteed sulphite free – something they acknowledge may not be as simple as it initially sounds. 90 percent of the shrimp consumed in the US is imported, usually from the countries listed in the study.

On the farming side of the value chain, shrimp producers can eliminate sulphites completely. Sulphite-free solutions to prevent melanosis are already on the market. Encouraging their adoption could be a critical step in de-risking farmed shrimp exports.