The shrimp aquaculture sector – from the production of feed ingredients to the processing plant – faces increasing scrutiny, but not much attention has been given to what happens to shrimp once it reaches its destination market.

© Madeline Craig

High-profile media reports have already illuminated problems such as the presence of slavery and forced labour in the seafood industry at large, as well as the widespread use of banned antibiotics, but the United States remains one of the largest and most open markets for farmed shrimp, despite these issues.

This means that shrimp that could be refused entry into the EU, Japan, or other major shrimp markets are likely to still be viable for shipment to the US. This has two main implications: an increase in the likelihood of threats to public health and safety, and the possibility for increased instance of food waste if imports are refused and discarded. The Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) publicly available import refusal records may be able to shed some light on the prevalence of certain contaminants in different exporting countries over time, as well as the volume of food waste associated with these import refusals.

Food production accounts for 70 percent of human water use, 25-35 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, and 38 percent of our total land use. It is well documented that we are currently using resources at one and half times the rate that the planet can sustain, and wasting a third of every calorie produced. Within that context, it should be clear that reducing any waste in the food industry should be a top priority. This is especially true for shrimp, as it is the number one seafood consumed in the US by volume (approximately 4lb per person annually).

Screening shrimp

So what is the process for screening shrimp aquaculture products intended for the US market? The US Customs and Border Patrol are the first to process and record a shipment; it then proceeds to the FDA. Using a predictive screening algorithm, which assesses instances of contamination, type of product, and the country/processor of last handling, the FDA’s predictive algorithm flags which incoming shrimp are at highest risk of contamination or infraction. FDA staff then physically examine only around 1 percent of all imported shrimp. Of that one percent, the ones that are found to have violated an FDA standard are detained and usually destroyed. The sheer volume of shrimp consumed in the US means that even this small percentage of detained product can represent a sizeable amount of waste.

The usual suspects

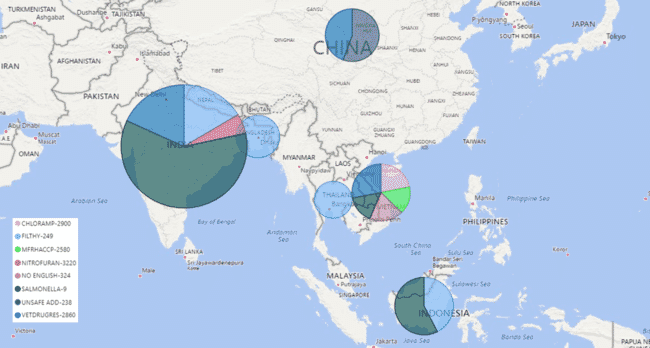

Between 2002 and 2018, the top five reasons for the detention of shrimp coming into the US were:

- The presence of salmonella

- Drug/antibiotic residue

- The product was found to be “filthy” or unfit for consumption

- It contained nitrofurans

- It contained any other “unsafe food additive”.

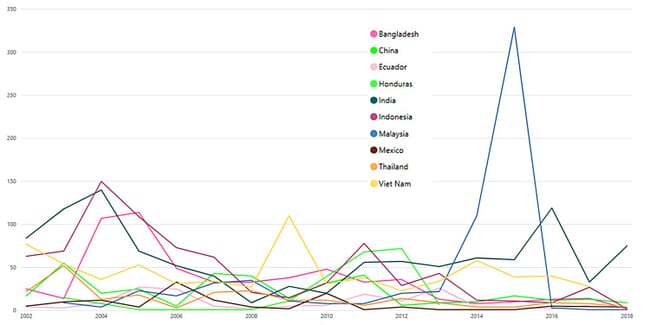

Three of these top five reasons for refusal – and more than half of the top ten – are due to the presence of a substance (usually an antibiotic) that was purposefully added to the product. It’s unsurprising that the countries that produce and export the most shrimp are also among the top offenders for contaminants and other violations by number, nevertheless it’s interesting to map these trends.

© Madeline Craig

Other top reasons for refusal include a simple failure to print the name of the processing company on the package, the absence of any English on the label, an absent or incomplete nutrition label, or evidence that the product has been packaged in unsanitary conditions. In many instances, a shipment was refused for not just one, but for multiple reasons. However, the idea that some of the discarded shrimp may have been perfectly fine to consume, but had to be discarded because of a lack of English on the label is hard to swallow. No one benefits from such an avoidable waste.

Within the industry, these problems have been more or less persistent over the course of the past 16 years, but they vary from country to country because of different lessons learned or tools developed. If these past trends could be utilised to help guide our expectations or management of growing markets, then some unnecessary food waste might be avoided. When we think about resource use in aquaculture, we tend to focus now on things like feed conversion ratio and farm management. A topic that isn’t necessarily the first to come to mind is the volume of resource waste represented by this discarded shrimp. Even if there was improved resource efficiency at the farm level, it does no good if the product reaches its intended destination only to be discarded.

It’s time to start holding the proverbial microscope to the import process for shrimp. A vast majority of the shrimp on US plates is produced in farms in other countries - as much as 92 percent, according to NOAA. That’s a lot of foreign shrimp that needs to pass muster, and the FDA just doesn’t have the capacity to test all or even most of the incoming shrimp. Moving forward, it would benefit the entire planet if more attention and resources were allocated to food regulatory bodies such as the FDA, both within the US and abroad, and if more care were taken with respect to product and shipment labelling and documentation.

Further information

A version of this article was first published in Aquaculture America.